Variations: Anaconda, Boi-úna, Cobra Grande, Cobra-grande, Eunectes murinus, Mae-d’agua, Mae-do-rio, Mboia-açu (“Large Snake”), Mboiúna; Mru-kra-o (Kayapo); Vai-bogo (Desana)

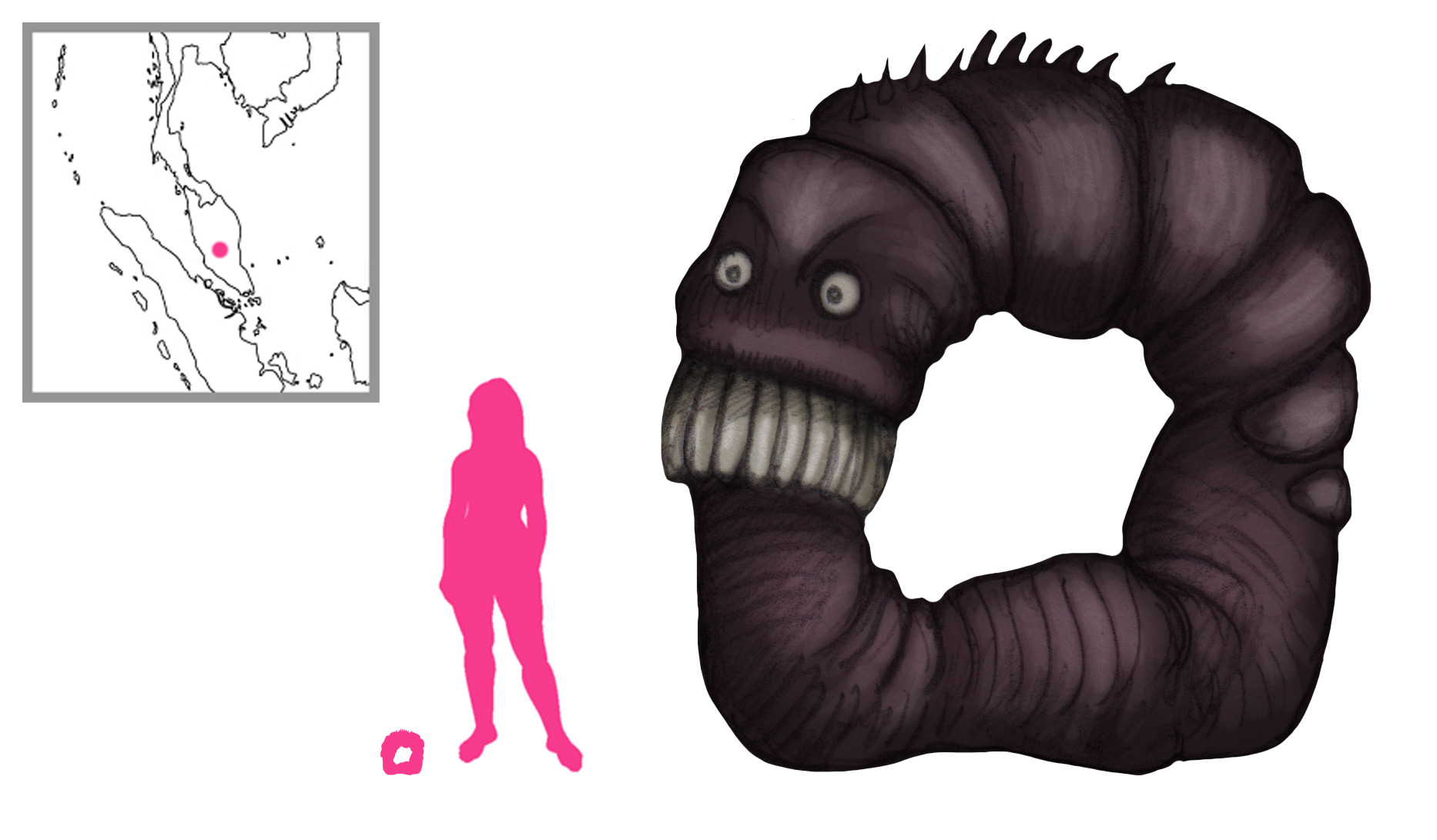

Boiúna or Cobra Grande is one of the most widespread and polymorphic myths of the Amazon basin. The name is applied to concepts and creatures ranging from a goddess of the water to a synonym of the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus).

In lingua geral the term boi denotes a snake (such as jiboia, the boa constrictor). Una means black. Thus a boiúna or mboiúna is a black snake, a name it shares with the mussurana. Its other name of cobra grande (“big snake”) is even less descriptive.

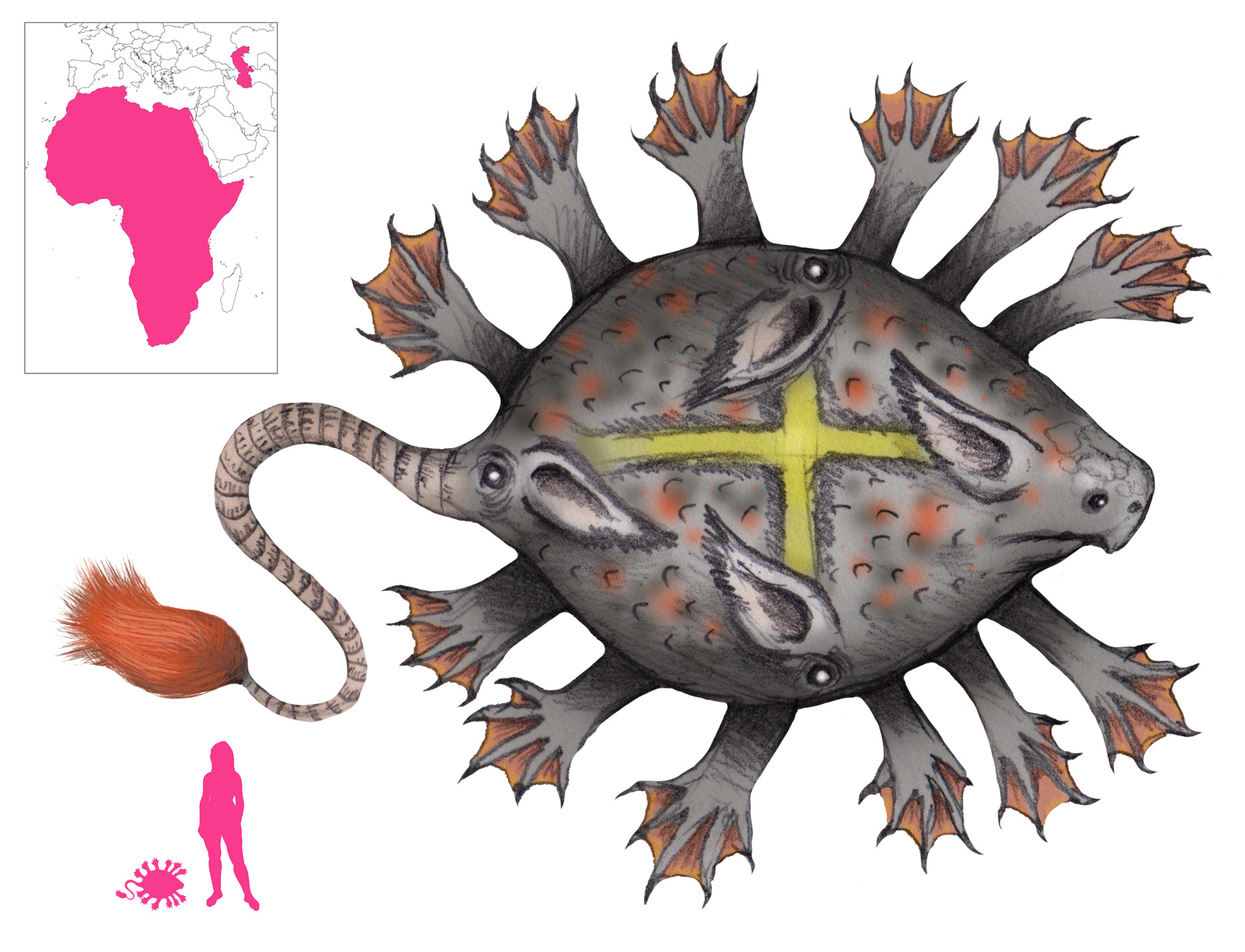

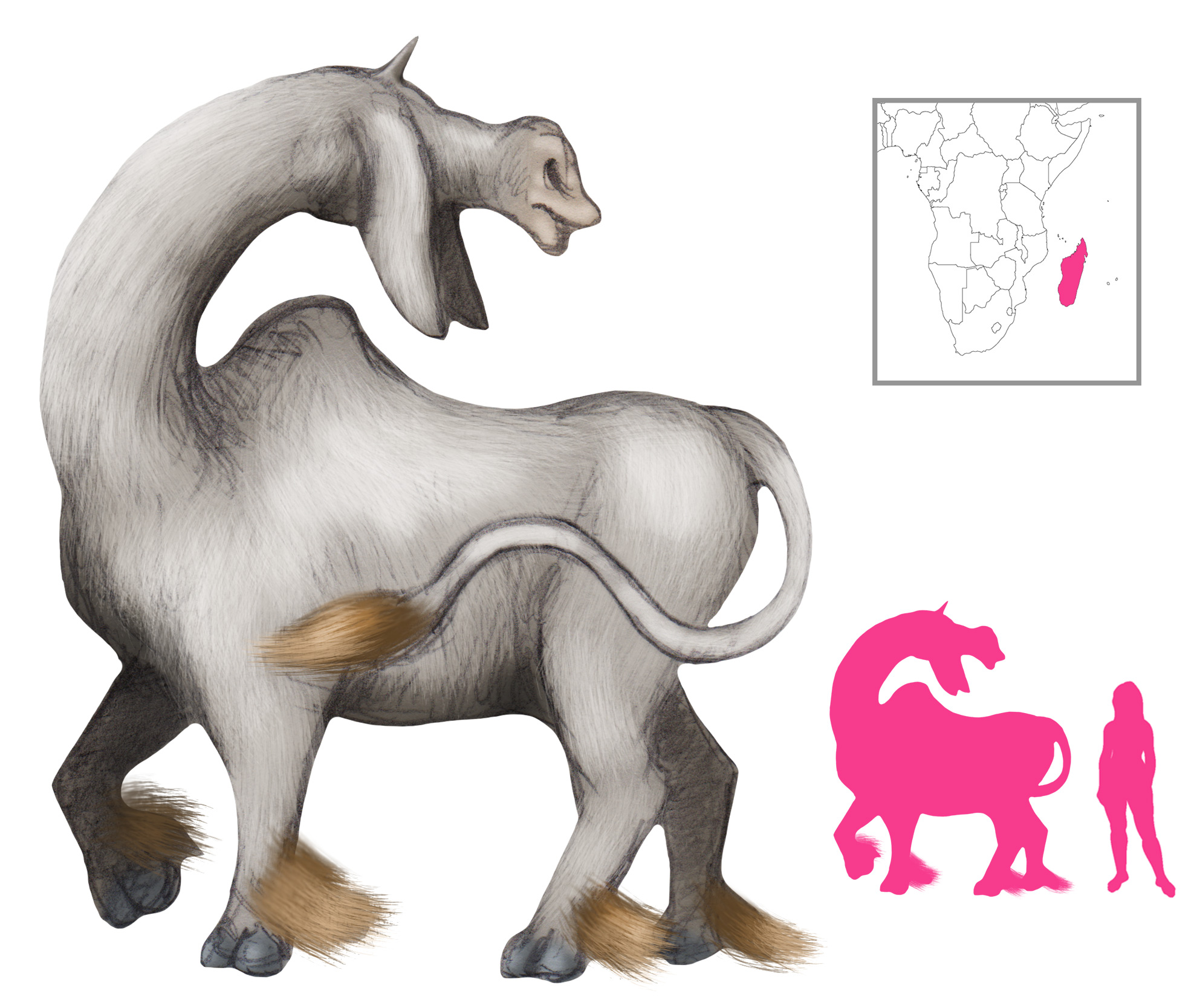

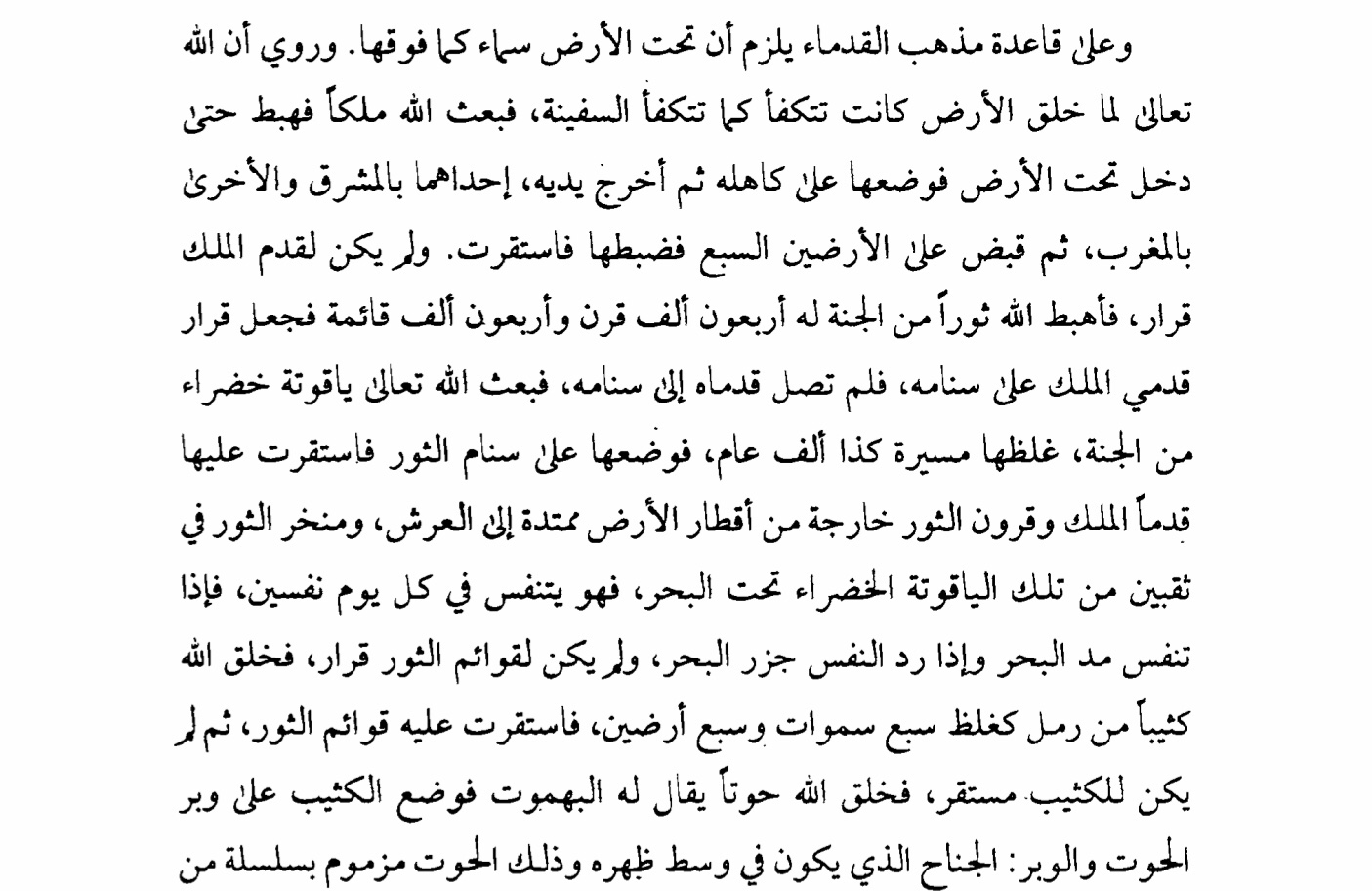

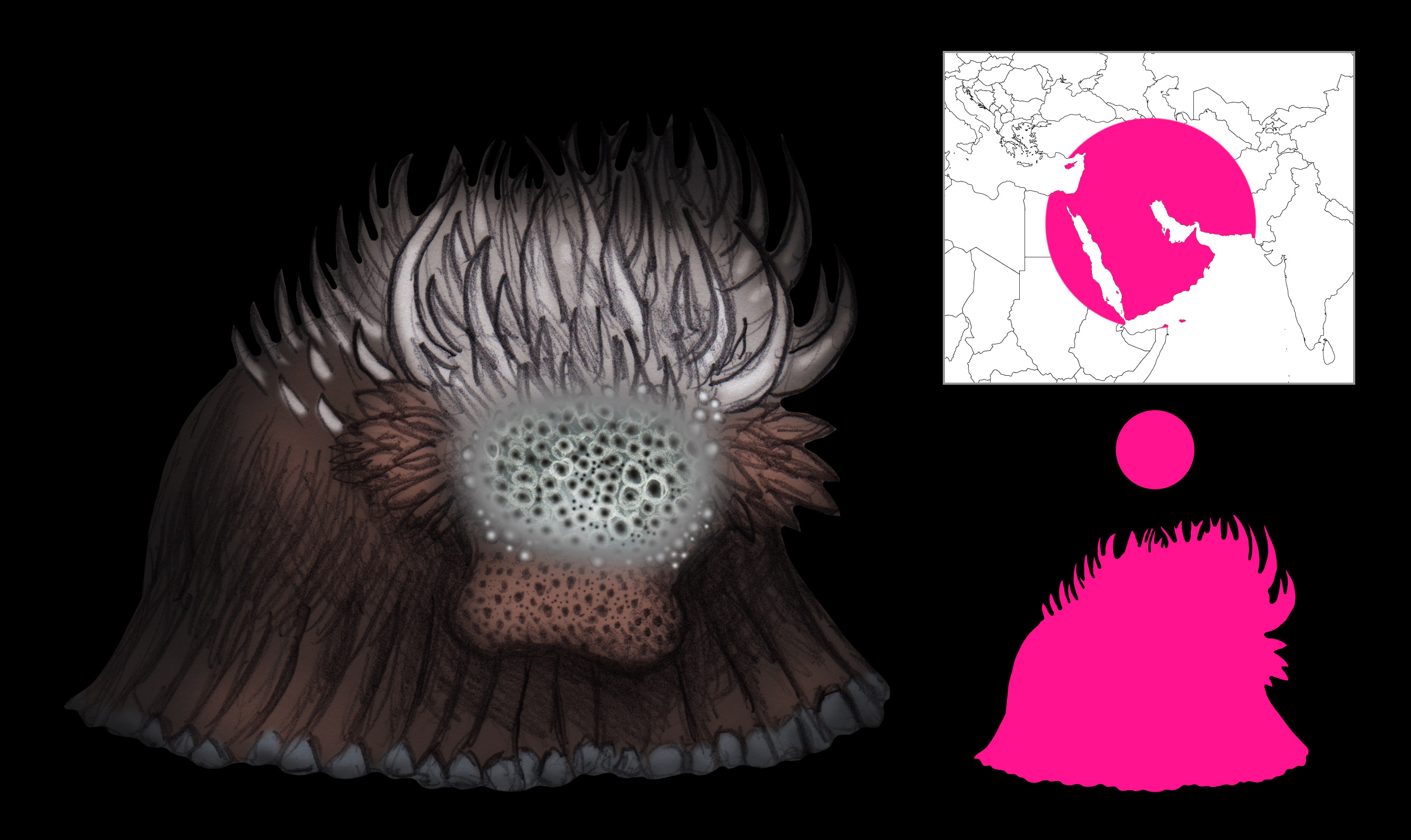

But a cobra grande is nothing if not big. It grows up to two hundred meters long and ten meters wide. Its enormous eyes, 0.5 to 1 m apart, glow like searchlights, with colors including orange-yellow and blue. Sometimes it has large, sharp canines on its lower jaw that stick out through holes in its upper jaw like horns. It has a powerful stench that can make people dizzy, and it makes loud rumbling sounds. Its massive bulk easily hides in the underwater holes it digs. Sometimes it appears as a ghost ship, a steamboat or a sailboat.

Boiúna can be found at the bottom of streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds, but it usually avoids the rainforest and dry land. When water levels fall in the dry season boiúnas slither out in search of deeper water, gouging out new stream channels and troughs. Its mere presence in the water can impregnate women.

When it swims a boiúna leaves a distinctive, huge, v-shaped bow wave. It protects the fish of its waters. It has a magnetic power that allows it to immobilize ships in the middle of the river, and release them at its discretion; inexplicable boat malfunctions can be ascribed to a meddling boiúna. The glowing eyes of a boiúna can mesmerize anyone who looks at them, rendering the victim enchanted (encantado). The snakes can also kill people by stealing their shadows. A de-shadowed person (assombrado) wastes away and dies in a few days. It can take a more direct approach by attacking small boats and eating the passengers, although it may also take its captives to its underwater kingdom, a sort of watery afterlife, to live with it as river snakes.

Boiúnas are intelligent. They can be summoned in séances, where they are quite talkative. They can also take on human form and mingle with people. Norato was a boiúna who would leave the Tocantins river and head into Carolina at night to party. He was an avid dancer who swapped his scaly hide for a dashing white jacket. A man once saw a giant snake leave the river and turn into a man, leaving his skin behind. Horrified, the onlooker decided to burn the skin. Norato returned to find that he was stuck as a human.

Sometimes a boa constrictor that grows too big becomes a boiúna. Sometimes a boiúna is spawned from human behavior. The boiúna of the Itacaiunas River was conceived by a girl who became pregnant and hid her condition from her parents. When she gave birth she was too scared to tell her parents, and threw the baby into the Itacaiunas. There it metamorphosed into a huge snake that terrorized river traffic. The boiúna revealed in a séance that it wanted to be disenchanted; the way to do so involved luring it with hot milk, slashing its throat, and turning around without looking back. Nobody took it up on the offer.

Tales of giant snakes are common throughout the Amazon. These include the mru-kra-o of the Kayapo and the vai-bogo of the Desana. In the Peruvian Amazon the giant anaconda is known as the Yakumama, the Mother of Water.

References

Barbosa, A. L. (1951) Pequeno Vocabulario Tupi-Portugues. Livraria Sao Jose, Rio de Janeiro.

Cascudo, L. C. (2000) Dicionario do Folclore Brasileiro. Global Editora, Sao Paolo.

Fonseca, F. (1949) Animais Peconhentos. Instituto Butantan, Sao Paolo.

Galeano, J. G.; Morgan, R. and Watson, K. trans. (2009) Folktales of the Amazon. Libraries Unlimited, Westport.

Osborne, H. (1986) South American Mythology. Peter Bedrick Books, New York.

Smith, N. J. H. (1981) Man, Fishes, and the Amazon. Columbia University Press, New York.

Smith, N. J. H. (1996) The Enchanted Amazon Rain Forest. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.