Variations: Animal Monstrueux (Monstrous Animal) (Paré); Testudo Polypus (Gesner)

Iambulus the Greek sailor saw many marvels on the Islands of the Sun. One of those is an unnamed animal, small, round, and similar to a tortoise. It has two diagonal yellow stripes on its body, with an eye and a mouth at each end of the stripes, giving it four eyes and four mouths around its body. It eats with all four mouths, which all lead into a single gullet and stomach; its inner organs are likewise single. This creature also has many feet which allow it to move in any direction it wishes. Most miraculous of all is its blood, which is endowed with such healing power that it can instantly reattach severed body parts. As long as the cut is fresh and the body part is not vital (a hand, a foot, a limb, and so on), the animal’s blood will glue it back on again.

The adventures of Iambulus were recalled by Diodorus Siculus and cheerfully dismissed by Lucian as “obviously quite untrue” but a highly entertaining story nonetheless.

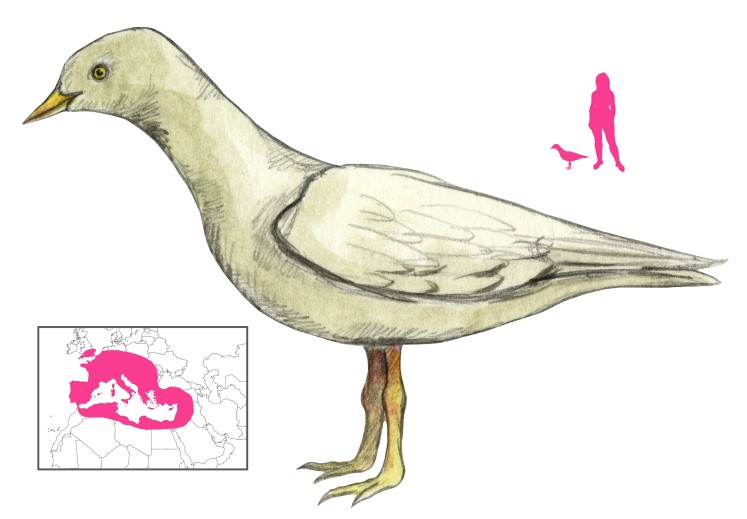

Temporal’s 1556 French translation of Leo Africanus’ works appends the travels of Iambulus and other seafaring yarns, lending them more credibility by association (or giving Leo’s accounts less credibility in the same manner). Translation errors have already set in, considering the adventures of Iambulus were translated into French by way of Tuscan. In Temporal’s version, the unnamed round animal now has two lines on its back in the form of a golden cross, and one eye and one ear at the end of each line, allowing it to hear and see in four directions. There is only one mouth through which the animal feeds. Its blood can cause any dismembered, still living body to come back together. The account is accompanied with a memorable image of the creature, with a long, thin tail ending in a tuft; the number of legs is fixed at twelve in the picture. Severed limbs surround the animal.

Is this the same as the Geluchart of the Caspian Sea? Thevet’s Cosmographie describes an animal called the geluchart, named after a nearby lake where it is also found in abundance. It has a head like a turtle’s (but much bigger), a small rat’s tail, and eight legs (four on each side). It is covered with scales and mottled with red and black spots. Thevet affirms that it is the tastiest fish in existence.

Thevet may have had the Iambulus creature in mind – specifically the illustration in the Temporal translation, as Thevet mentions the rat’s tail present in the image but not in the text. Either way, Vallot lumps them together, along with Gesner’s Testudo Polypus (“Many-legged Turtle”). For lack of a better term “geluchart” has been adopted as a title for this entry.

Paré’s unnamed “monstrous animal” is taken directly from Temporal’s Iambulus, with an image copied from that account. Paré erroneously credits Leo Africanus with describing the “very monstrous animal” but otherwise repeats the attributes given to it, including blood capable of sealing any wound. The description mentions several legs as well as establishing a “rather long” tail, “the end of which is heavily tufted with hair”. Its location is moved from Iambulus’ mythical island; it is now “born in Africa”.

Vallot attributes the ocellated pufferfish as the origin of this creature, but surely its origin in ancient Greek utopian fiction makes such association futile? Its wondrous properties cause Paré to wax poetic. “But who is it who would not marvel greatly on contemplating this beast, having so many eyes, ears, and feet, and each doing its office? Where can be the instruments dedicated to such operations? Truly, as for myself I lose my mind, and would not know what else to say, other than that Nature has played a trick to make the grandeur of its works be admired”.

References

Diodorus; Oldfather, C. H. trans. (1967) Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes, v. II. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Gessner, C. (1586) Historiae Animalium Liber II: Quadrupedibus Oviparis. Johannes Wecheli, Frankfurt.

Leo Africanus; Temporal, J. trans. (1556) De l’Afrique. Jean Temporal, Lyon.

Leo Africanus; Temporal, J. trans. (1830) De l’Afrique. Gouvernement de France, Paris.

Lucian; Turner, P. trans. (1961) Satirical Sketches. Penguin Books, London.

Paré, A. (1614) Les Oeuvres d’Ambroise Paré. Nicolas Buon, Paris.

Paré, A. (1996) Des Monstres et Prodiges. Fleuron, Paris.

Thevet, A. (1575) La Cosmographie Universelle. Guillaume Chaudiere, Paris.

Vallot, D. M. (1834) Mémoire sur le Limacon de la Mer Sarmatique. Mémoires de L’Académie des Sciences, Arts, et Belles-Lettres de Dijon, Partie des Sciences, Frantin, Dijon.