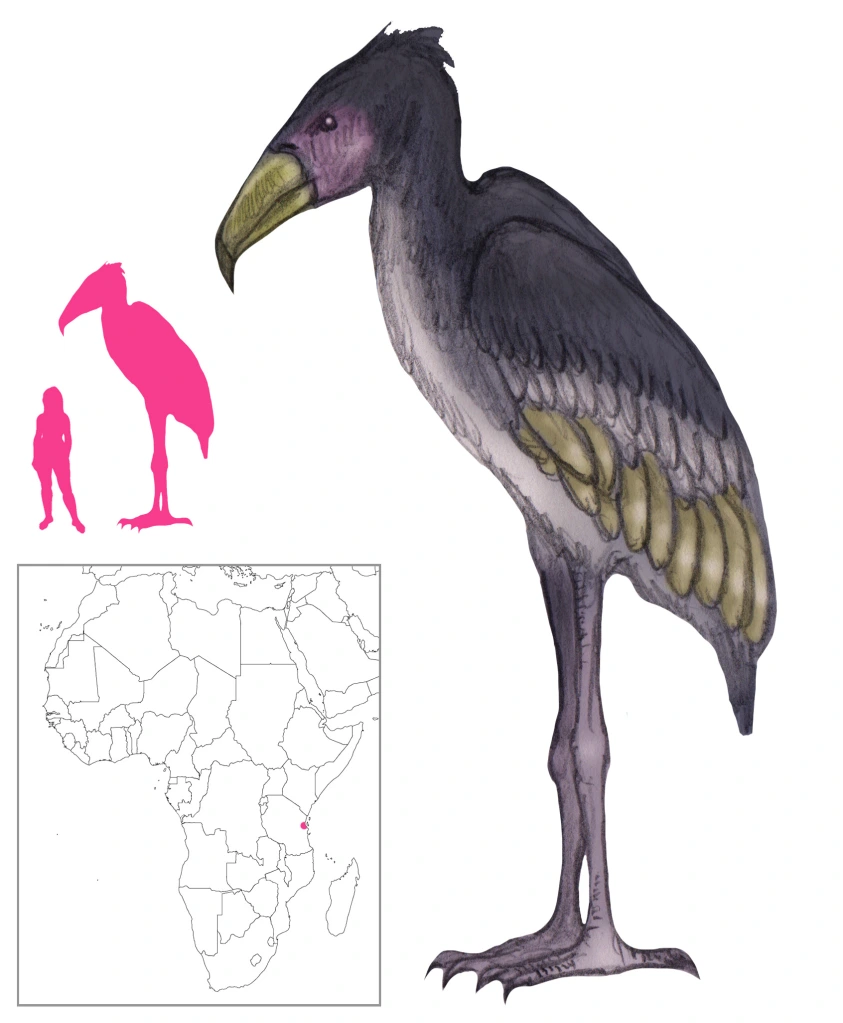

Variations: Moha, Great Barrier Sea-serpent, Great Barrier Reef Sea-serpent, Chelosauria lovelli

The Moha-Moha was seen on a beach on Great Sandy Island by schoolteacher Selina Lovell and a small group of accompanying people on June 8, 1890. It was, however, familiar to the natives of the region by the name moha-moha, “dangerous turtle”. It was known to attack coastal camps and catch people by the leg. By January 3, 1891, details of the encounter were published in Land and Water. This in turn resulted in a more formal description by William Saville-Kent, who requested further details from Lovell and gave the creature the name of Chelosauria lovelli.

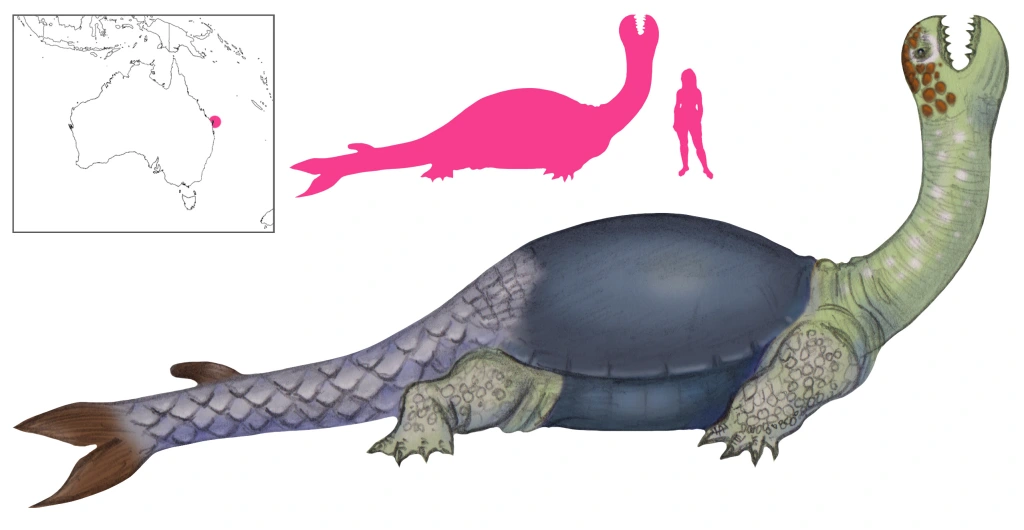

A “monster turtle fish”, the moha-moha was 30 feet long, with an enormous dome-shaped body, a long neck, and a twelve-foot-long tail. It allowed Lovell to observe it for half an hour while standing five feet away from it. Then it turned towards the sea, raising its body and tail above the water and tossing a number of fish into the air before dashing off into deeper water.

The moha-moha had a saurian face, with teeth or serrated jaw-bones. The skin was glossy and smooth as satin. It had its mouth open and visible above the water, and no visible nostrils, leading Lovell to conclude that it breathed through its mouth. The rounded jaws were 18 inches long. The head and neck were a greenish white with white spots on the neck and a white band around a very black eye.

The dome-shaped carapace, about 8 feet across by 5 feet high, was slate-grey in color and smooth. The long tail was silver shading to white with thumb-nail sized scales and a chocolate-brown fin. The scales lay perpendicular to the tail, like the tiles of a roof. The head and tail were very different from each other, looking like they had come from two different animals. Lovell was unable to see the feet, but she was told that the moha-moha had feet like an alligator.

Whatever it was that Lovell saw, she was immediately treated with condescension. Buckland, editor of Land and Water, believed the moha-moha to have been a Carettochelys, “a monster turtle” from the Fly River (despite the fact that Carettochelys does not exceed 30 inches in length). He added that “the fair observer must have been mistaken on this very important point”. Lovell responded indignantly, but the editor stood by his statement, making it clear that the moha-moha combined fish and tortoise and thus was scientifically impossible.

To Saville-Kent, Lovell sent a confirming document signed by her and all the witnesses present. But Saville-Kent’s description of the moha-moha takes on a mocking tone, recommending using it as “the chief ingredient… of a new and alderman-enthralling brand of turtle soup”. It won’t be long before moha-moha is on restaurant menus, and the “Queensland brand-new, soup-potential species should possess “a local habitation and a name” that shall separate it decisively from the common herd of sea-serpents that have already had their day”.

Heuvelmans took a very negative view of the moha-moha, which all the more remarkable considering his unquestioning acceptance of far more ambiguous sightings. He refers to the “innocence and ineptitude” of the parties involved, and states that “with all due respect to her sex, [Lovell] can only be an arrant liar, and a bad liar at that”, accusing her of “psychotic behavior” and “mythomania”. He proceeds to discredit her account, pointing out that no animal has scales like the moha-moha. “One pities her poor pupils, for her own style is often so confused as to be incomprehensible”, he adds snidely. He compares its shelled, fish-like appearance to both armored Devonian fishes and the Indian makara. “I find it hard to believe that Miss Lovell was not a dotty old maid who had picked up, but not digested, a smattering of palaeontology and Brahmin legend. Exit Chelosauria lovelli.”

What, then, did Lovell see on that beach in 1890? Most telling is the remark that the head and tail do not seem to belong on the same animal. France suggests a turtle entangled in a fishing net, with the mesh and its contents – broken floats, brown seaweed, and other debris – giving the impression of a long tail. Unfamiliarity and the unreliability of recollection did the rest. Native accounts of moha-moha attacks and ferocity may refer to other animals, perhaps seals.

References

France, R. L. (2016) Historicity of sea turtles misidentified as sea monsters: a case for the early entanglement of marine chelonians in pre-plastic fishing nets and maritime debris. Coriolis, 6(2), pp. 1-25.

France, R. L. (2017) Imaginary sea monsters and real environmental threats: reconsidering the famous Osborne, ‘Moha-Moha’, Valhalla, and ‘Soay Beast’ sightings of unidentified marine objects. International Review of Environmental History, 3(1), pp. 63-100.

Heuvelmans, B.; Garnett, R. trans. (1968) In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents.

Saville-Kent, W. (1893) The Great Barrier Reef of Australia. W. H. Allen & Co., Waterloo Place, London.