Variations: Nykur Hestur (Nykur Horse), Nickur; Nennir, Ninnir (Ninny); Flóðhestur (Hippopotamus); Kumbur (Clump); Skolli (Devil); Vatnaskratti (Water Fiend)

The Nykur or Nennir is the water-horse of Iceland. It is found across the island in association with pools, lakes, ponds, rivers, and the sea, and accounts of its misdeeds date as far back as the Book of Settlements. Its name follows the naming tradition of water-creatures across northern Europe, including the Baltic Nixa, the Germanic Nixy, and the Netherlandish Nikker. Suggested etymologies for this naming group include Nick (as in Old Nick, the devil), an Indo-Germanic root meaning “black” or “dark” (compare Latin niger, for instance), or nihhus, an Old High German word for crocodile.

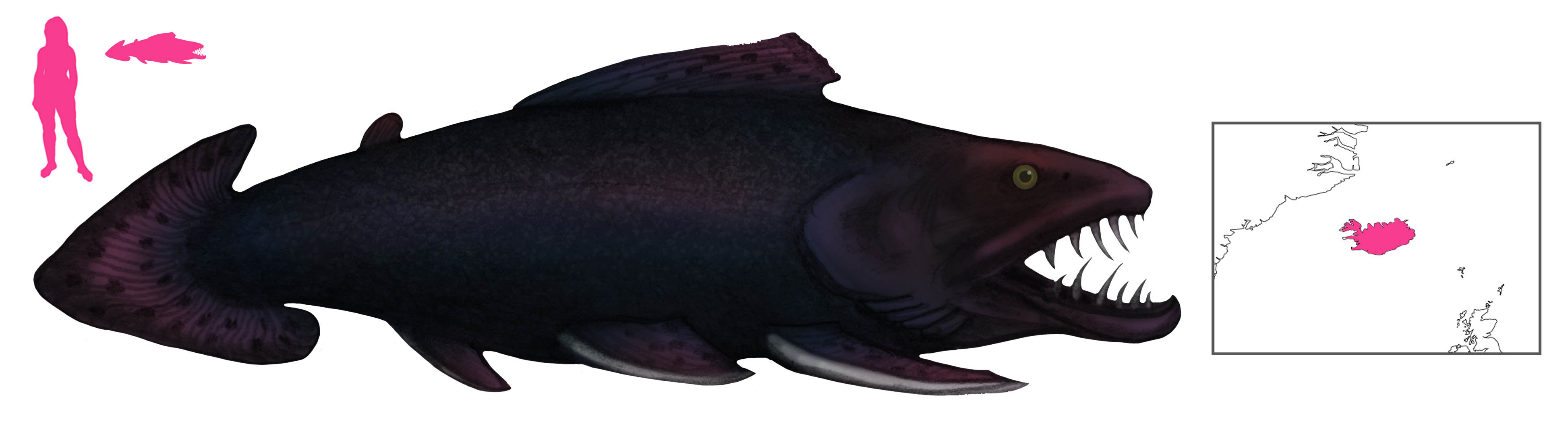

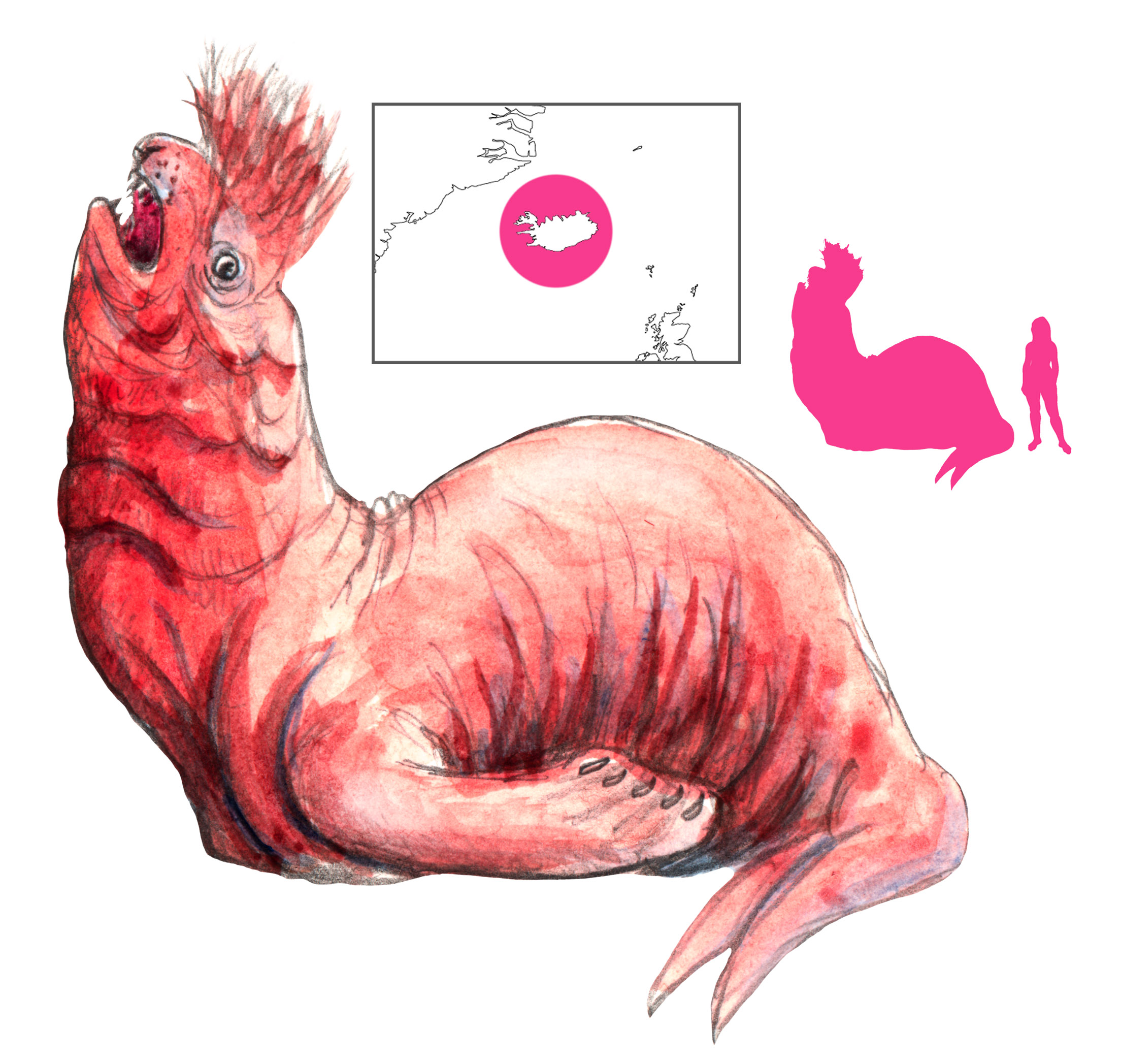

A nykur is a horse, usually grey in color, with reversed hooves. Coat variations include dapple grey and black, but pink, white, yellow, and grey with a dark streak on the back have been reported. Red cheeks are possible, as is a blaze that gives the impression of a single eye. The mane may be of a different color. The neck is short. The hooves are uncloven, and the tufts on the pasterns also point backwards. It will not allow anyone to inspect its hooves. A nykur can change shape at will, although shapeshifting is not a major part of its myth. It has been said to also appear as a wild, unmilkable cow with reversed hooves, or as a giant salmon or other fish. In the Elenarljóð ballad, the nykur takes on the form of a handsome young man to woo the heroine in hopes of drowning her. More monstrous appearances include twelve-legged forms, or massive, stout beasts with dragging bellies, protruding heads, and skin hanging in heavy folds.

Nykurs are malicious and cruel creatures. They present themselves as tame, friendly horses, but anyone who mounts them will find themselves sticking to the nykur’s back, as if held fast by glue. The nykur then gallops wildly off into the sea, plunging its rider into the water and drowning them. Nykurs will also break the ice on lakes to drown people ice-fishing. The booming sound of breaking ice is said to be the neighing of the nykur.

Nykurs beget foals with normal mares, but only if they are in the water. Horses descended from nykurs will lie down and roll over whenever ridden or led through water as high as their bellies.

As long as there is no water within sight, it is safe to ride a nykur. If a nykur is detected in the vicinity of a body of water, it should be scared off to prevent potential disaster. Nykurs hate fire, and keeping a fire burning nearby for a whole day will make it move elsewhere. They also avoid holy water.

With the right approach, a nykur can be caught, tamed, and forced to work. There is a swelling under a nykur’s left shoulder. If the swelling is punctured, the nykur becomes safe to ride, and loses its harmful nature, but the lump may return with time.

Nykurs hate to hear their name. If they hear the word nykur or nennir – or indeed, any word similar to it – they buck and shy and gallop away into the water. They also dread hearing the names of God and the Devil, and the sound of church bells; making the sign of the cross also repels them. A shepherd girl who prepared to mount a nykur exclaimed “Eg nenni ekki á bak!” (“I don’t feel like getting on its back!” Hearing the word nenni, the nennir galloped away and vanished into a lake. In another tale, a group of children mounted a nykur, but the oldest and wisest child held back, saying “I don’t feel like getting on its back”. The nykur ran off with its riders and drowned them, leaving the eldest to tell the sad tale. The heroine of the Elenarljóð ballad has a similar stroke of homophonic luck.

Butter-lake Heath, in the east of Iceland, got its name from a nykur-related incident. A servant girl left a farm to sell butter in the village of Vopnafjörthur. Along the way she grew tired, and was grateful to find a tame grey horse standing unattended. She mounted the horse and continued along her way, but the moment the horse saw the nearest lake, it dashed into it, drowning the girl. Thus the lake earned the name of Butter Lake, and the surrounding heath became Butter-lake Heath.

The nykur of Svarfathardale, near to the northern town of Akureyri, was known to live in deep pools by the river. The inhabitants of the village chased it off by building fires around the pools and throwing burning coals into the river all day. The nykur was scared off, and there have been no drownings since.

In Grimsey it was said that a nykur lived in the sea and neighed every time the islanders returned to the mainland for a cow. The neigh of the nykur drove the cows mad, causing them to jump into the sea and drown. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the people of Grimsey dared keep cows on the island.

There are places all over Iceland named for the nykur, from Nykurborg to Nykurvatn.

References

Árnason, J.; Powell, G. E. J. and Magnússon, E. trans. (1864) Icelandic Legends. Richard Bentley, London.

Benwell, G. and Waugh, A. (1961) Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin. Hutchinson, London.

van Hageland, A. (1973) La Mer Magique. Marabout, Paris.

Hlidberg, J. B. and Aegisson, S.; McQueen, F. J. M. and Kjartansson, R., trans. (2011) Meeting with Monsters. JPV utgafa, Reykjavik.

Rose, C. (2000) Giants, Monsters, and Dragons. W. W. Norton and Co., New York.

Simpson, J. (1972) Icelandic Folktales and Legends. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Stefánsson, V. (1906) Icelandic Beast and Bird Lore. The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 19, no. 75, pp. 300-308.