Variations: Myrmecoleo, Myrmekoleon, Mermecoleon, Mermecolion, Mirmicaleon, Mirmicoleon, Murmecoleon, Formicaleon, Ant-Lion, Antlion

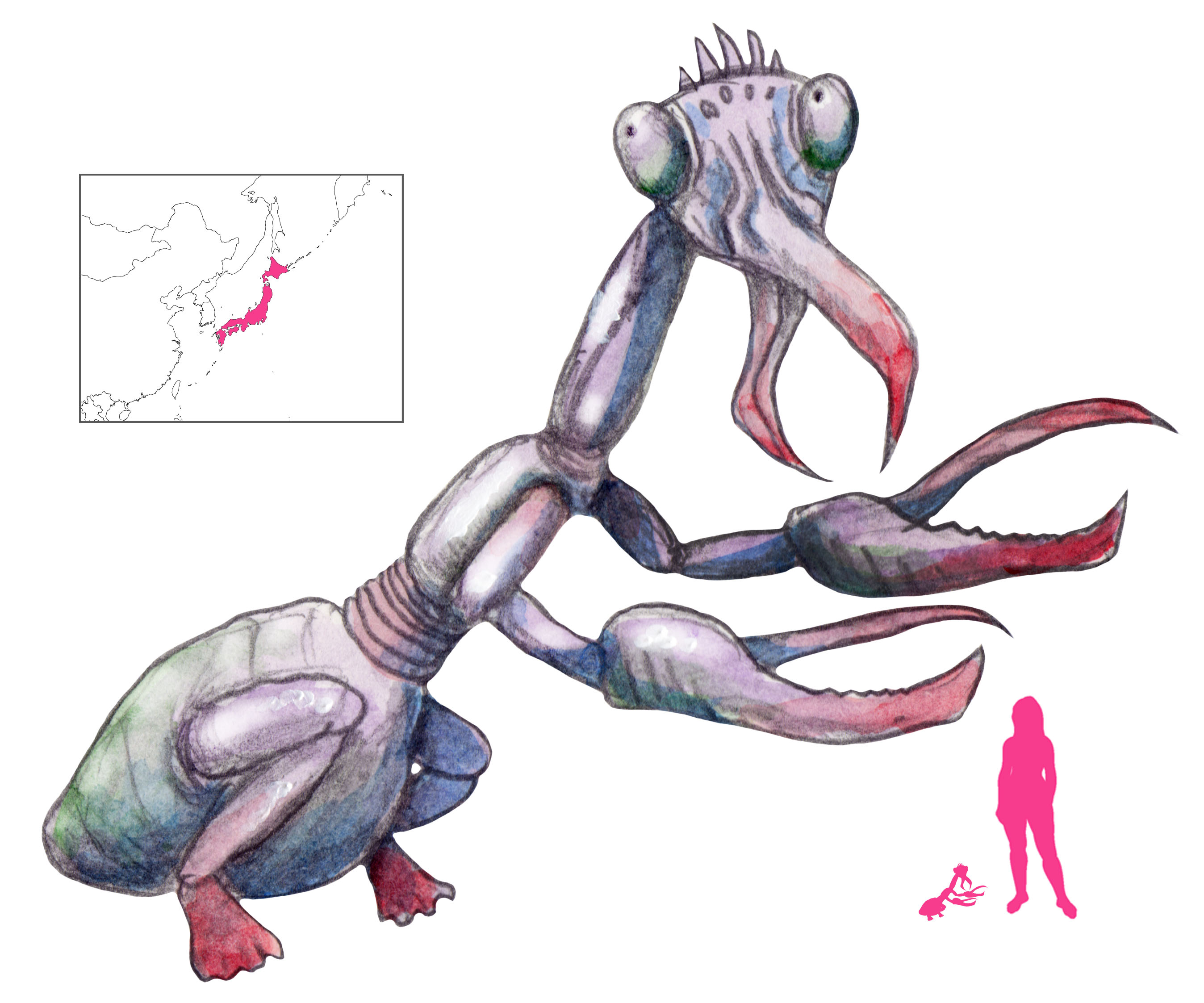

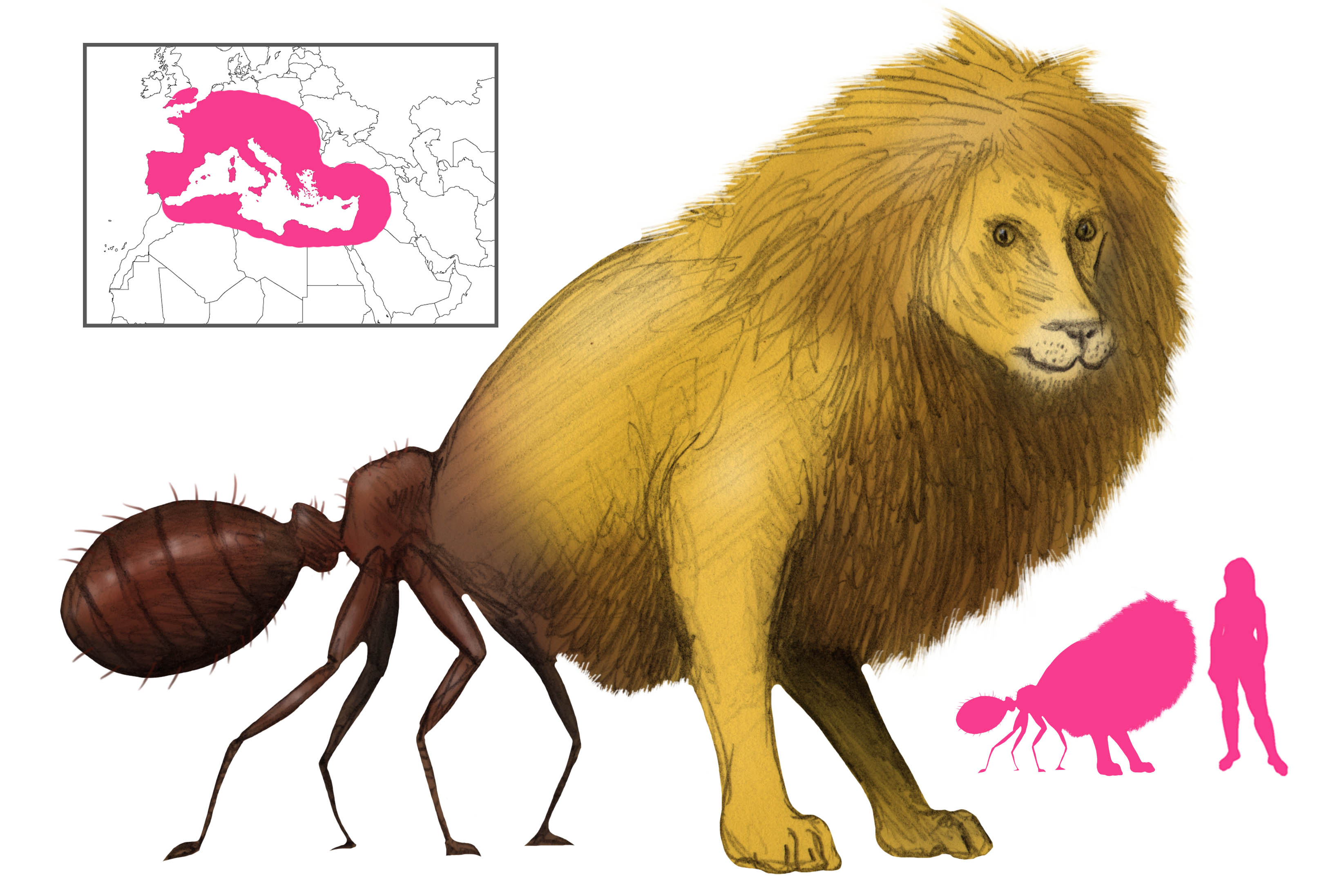

The Myrmecoleon, or Ant-lion, is a tale of two creatures and many translation errors. Druce distinguishes between the Eastern myrmecoleon, a hybrid of lion and ant, and the Western myrmecoleon, a carnivorous insect. These are one and the same, but the vagaries of translation led them down separate paths.

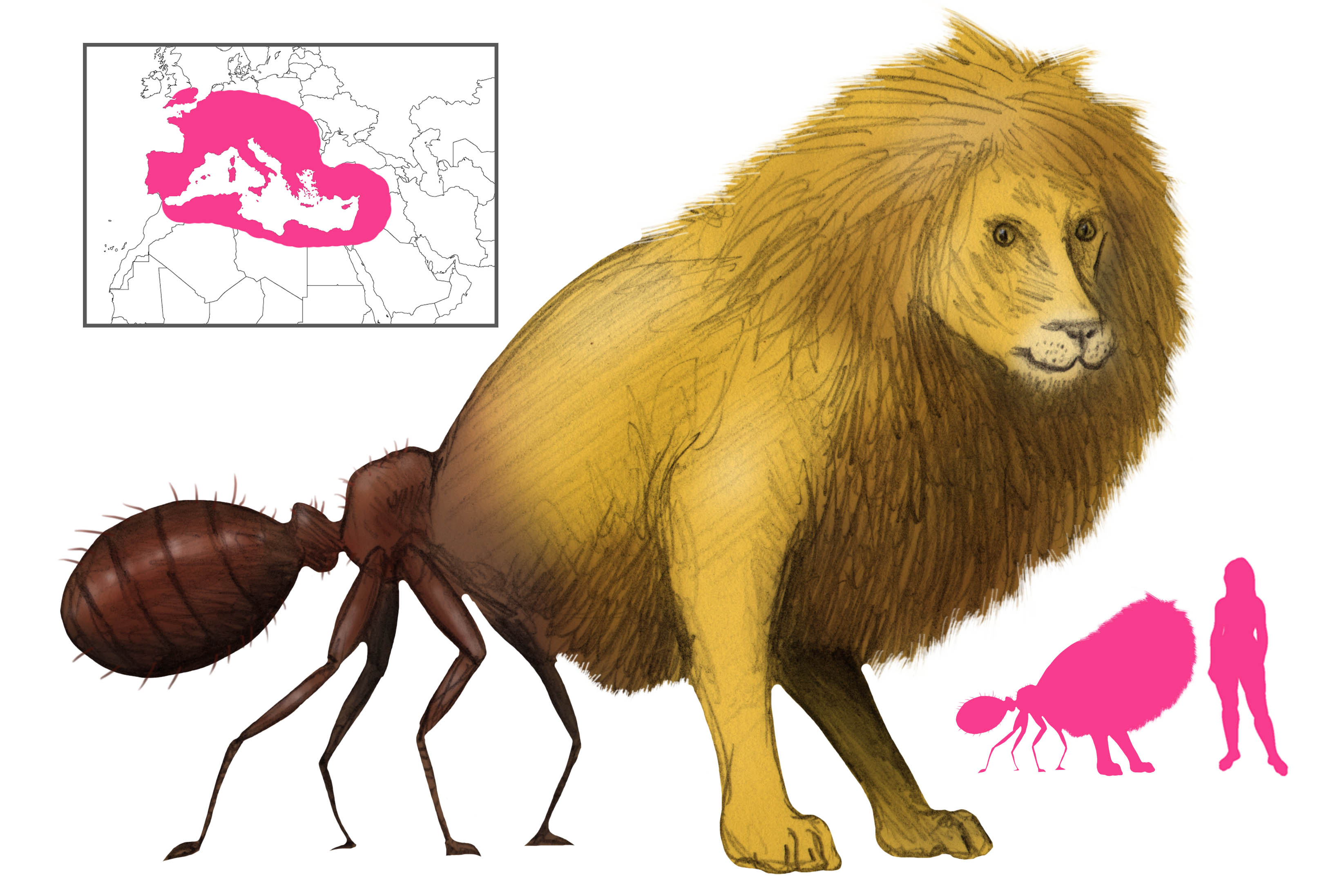

The Eastern myrmecoleon is found primarily in Greek, Arabian, Armenian, Ethiopian, and Syrian bestiaries. Its pedigree can be traced back to the giant gold-digging ants originally described by Herodotus. Further additions were added to the account as it evolved away from its origin. Nearchus claimed that the skins of the ants were as large as those of leopards. Pliny said that the horns of an Indian ant at the Erythraean temple of Hercules were remarkably large. Agatharchides, Aelian, and Strabo tell of Arabian and Babylonian lions called “ants” (myrmex) that have gleaming golden fur and reversed genitals (probably hyraxes, which have a distinctive dorsal gland).

The translators of the Septuagint were faced with the unfamiliar term lajisch or layish in Eliphaz’s phrase “the old lion perishes for lack of food” (Job 4:11). In the Vulgate it was rendered as tigris, and modern translations use “old lion”, but the Septuagint, drawing on obscure Classical species of lion, arbitrarily used the term myrmekoleon. Its name presupposes a hybrid of ant and lion; as the Bible is inerrant, this led led to the necessary existence of a creature whose father was a lion and whose mother was an ant. The fruit of this improbable union is a lion in front and an ant behind, and dies of starvation since the ant half cannot digest what the lion half eats, while the lion half cannot eat the plants the ant half requires. Thus “the myrmecoleon perishes for lack of food” became a logical statement, and was expounded upon in the Physiologus.

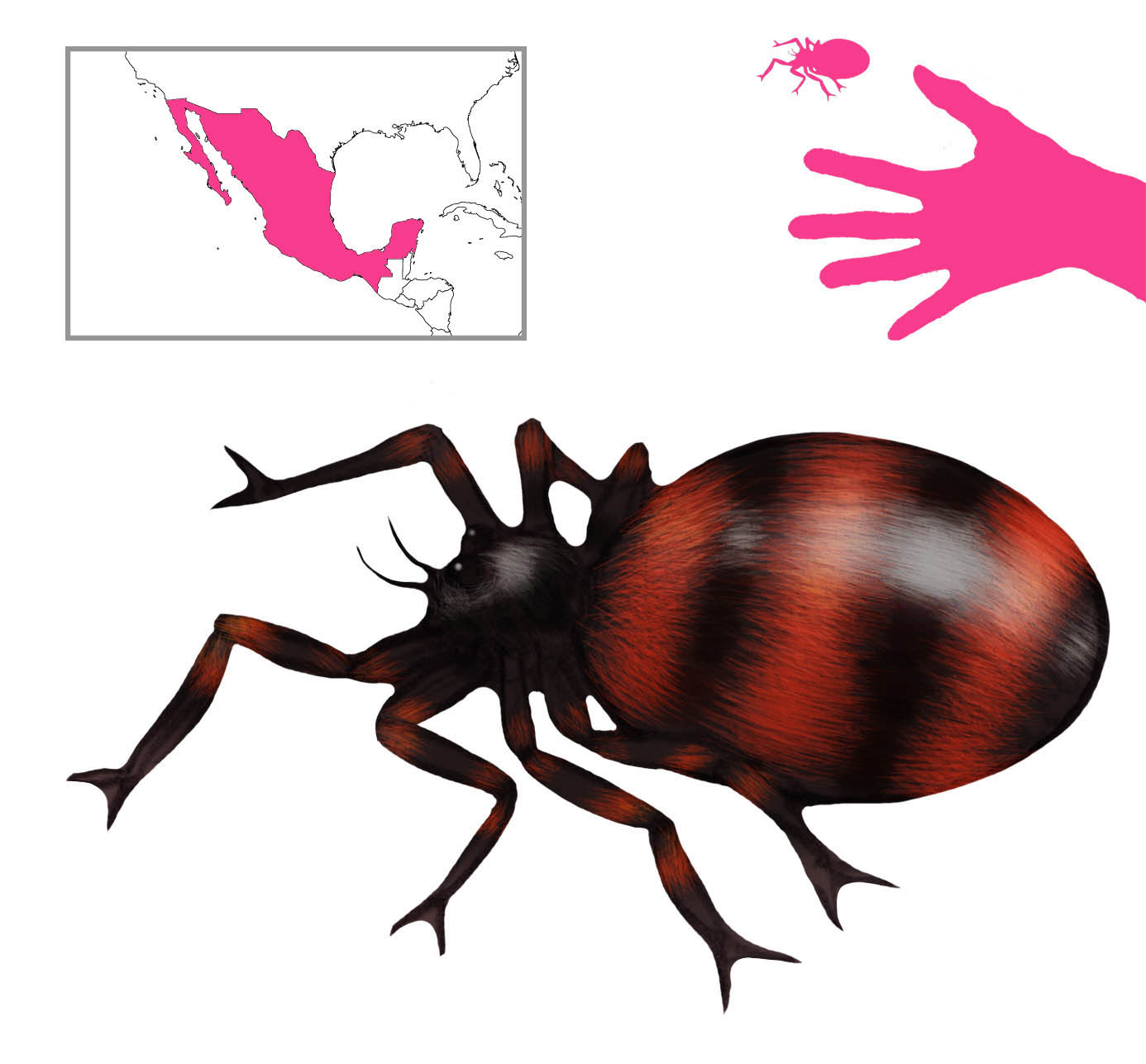

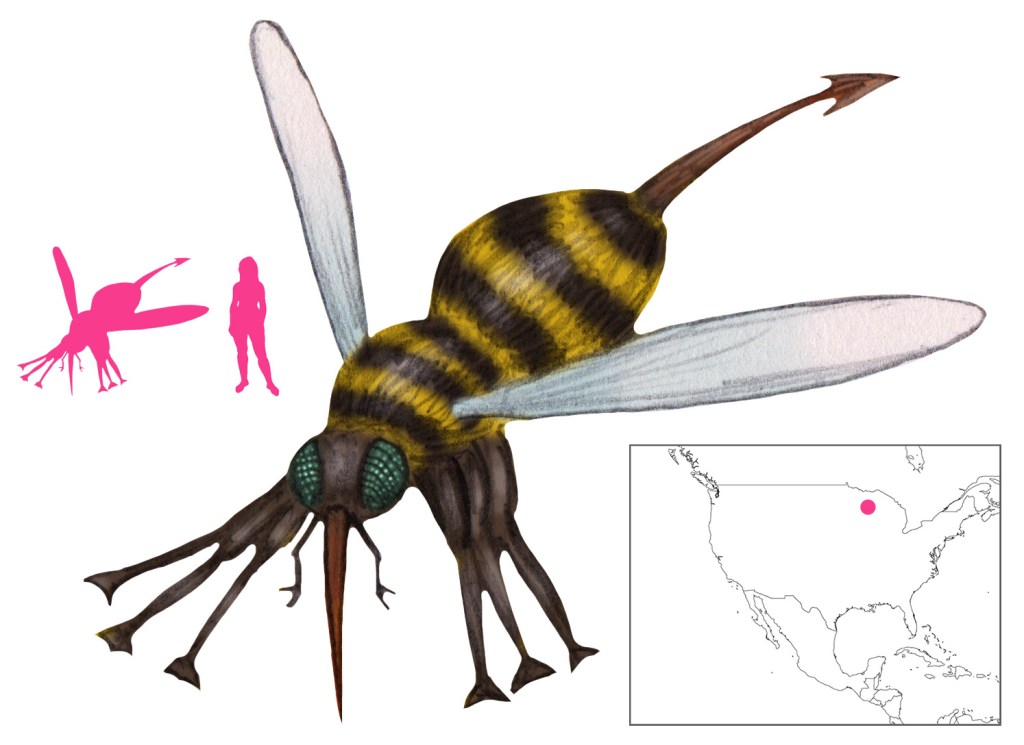

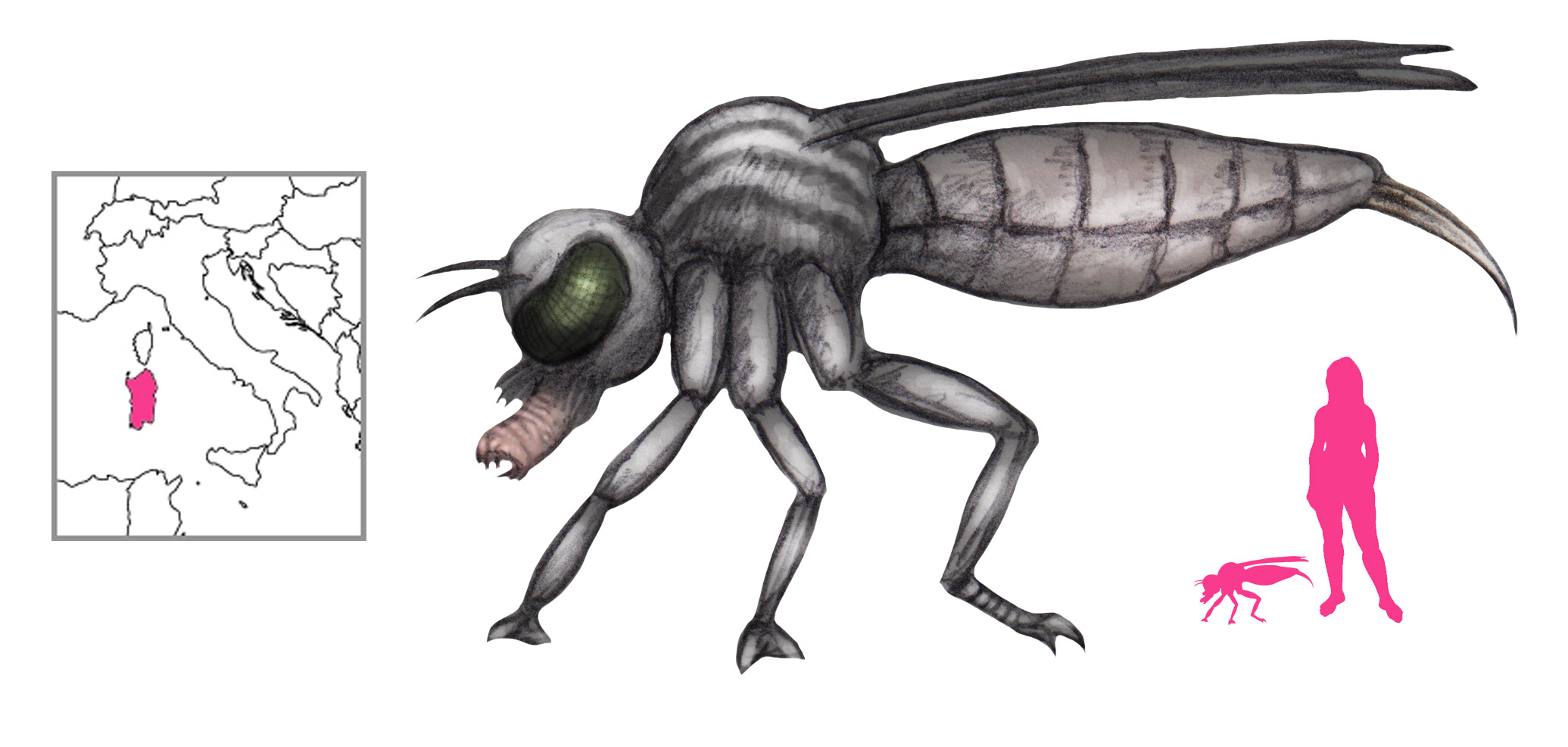

The Western myrmecoleon originally appeared in Latin sources and subsequently found its way into European bestiaries. This ant-lion is both ant and lion – an insect that preys on ants as lions prey on other animals, an ant to us, a lion to ants. It is an ant with a white head and a black body marked with white spots. It appears in bestiaries as something like a large ant or spider. This is a real animal – the antlion is a larva with huge jaws that constructs funnel-shaped traps in sand to catch ants. It eventually metamorphoses into a lacy-winged fly, but both larva and adult are completely harmless to humans.

The Western myrmecoleon originally appeared in Latin sources and subsequently found its way into European bestiaries. This ant-lion is both ant and lion – an insect that preys on ants as lions prey on other animals, an ant to us, a lion to ants. It is an ant with a white head and a black body marked with white spots. It appears in bestiaries as something like a large ant or spider. This is a real animal – the antlion is a larva with huge jaws that constructs funnel-shaped traps in sand to catch ants. It eventually metamorphoses into a lacy-winged fly, but both larva and adult are completely harmless to humans.

As a denizen of bestiaries the ant-lion has its own religious connotations. The Eastern myrmecoleon is two-faced, double-minded, unstable, and deceitful. The Western myrmecoleon represents Satan lying in wait for sinners.

References

Beavis, I. C. (1988) Insects and other Invertebrates in Classical Antiquity. Alden Press, Osney Mead, Oxford.

Borges, J. L.; trans. di Giovanni, N. T. (1969) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Clarke, Irwin, & Co., Toronto.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Druce, G. C. (1923) An account of the Μυρμηκολέων or Ant-lion. The Antiquaries Journal, 3(4), pp. 347-364.

Flaubert, G. (1885) La Tentation de Saint Antoine. Quantin, Paris.

Isidore of Seville, trans. Barney, S. A.; Lewis, W. J.; Beach, J. A.; and Berghof, O. (2006) The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Newbold, D. (1924) The Ethiopian Ant-lion. Sudan Notes and Record, 7(1), pp. 133-135.

Robin, P. A. (1936) Animal Lore in English Literature. John Murray, London.

The Western myrmecoleon originally appeared in Latin sources and subsequently found its way into European bestiaries. This ant-lion is both ant and lion – an insect that preys on ants as lions prey on other animals, an ant to us, a lion to ants. It is an ant with a white head and a black body marked with white spots. It appears in bestiaries as something like a large ant or spider. This is a real animal – the antlion is a larva with huge jaws that constructs funnel-shaped traps in sand to catch ants. It eventually metamorphoses into a lacy-winged fly, but both larva and adult are completely harmless to humans.

The Western myrmecoleon originally appeared in Latin sources and subsequently found its way into European bestiaries. This ant-lion is both ant and lion – an insect that preys on ants as lions prey on other animals, an ant to us, a lion to ants. It is an ant with a white head and a black body marked with white spots. It appears in bestiaries as something like a large ant or spider. This is a real animal – the antlion is a larva with huge jaws that constructs funnel-shaped traps in sand to catch ants. It eventually metamorphoses into a lacy-winged fly, but both larva and adult are completely harmless to humans.