Variations: Wakmabitchi Warak Wakkimbi (“Primordial Head of the Strong-Teethed Swine Family”)

Wakmangganchi Aragondi was the greatest and most terrifying monster in the folklore of the Garo people of India. This primordial demon once lay waste to the Garo Hills before it was slain by the god Goera.

Long before Goera’s birth, his maternal uncles descended into the subterranean region along with the fisherman Gonga Tritpa Rakshanpa and his dog. From there they took the progenitor of all the world’s birds back to the surface. The three uncles also brought with them a little pig, which they named Wakmabitchi Warak Wakkimbi.

The tiny piglet was kept in sty made of rocks, and there it grew and grew, until the sty had to be torn down to set it free. By then the pig was so big it could no longer be controlled; it wandered at will, feeding wherever and whenever it liked. People continued to feed it from a safe distance, until the day when it knocked the three uncles into its feeding trough and ate them alive. From then on, nobody dared approach it, and it continued to grow and increased in power. From then on it became known as Wakmangganchi Aragondi.

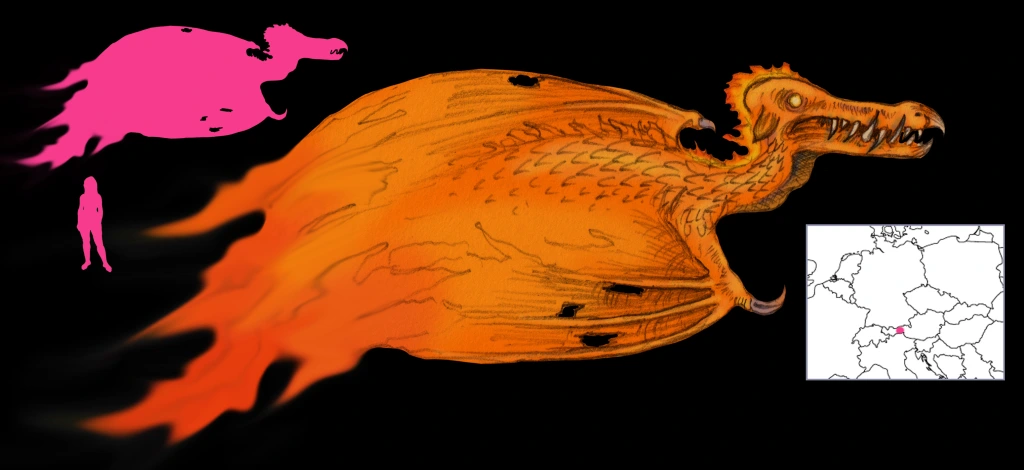

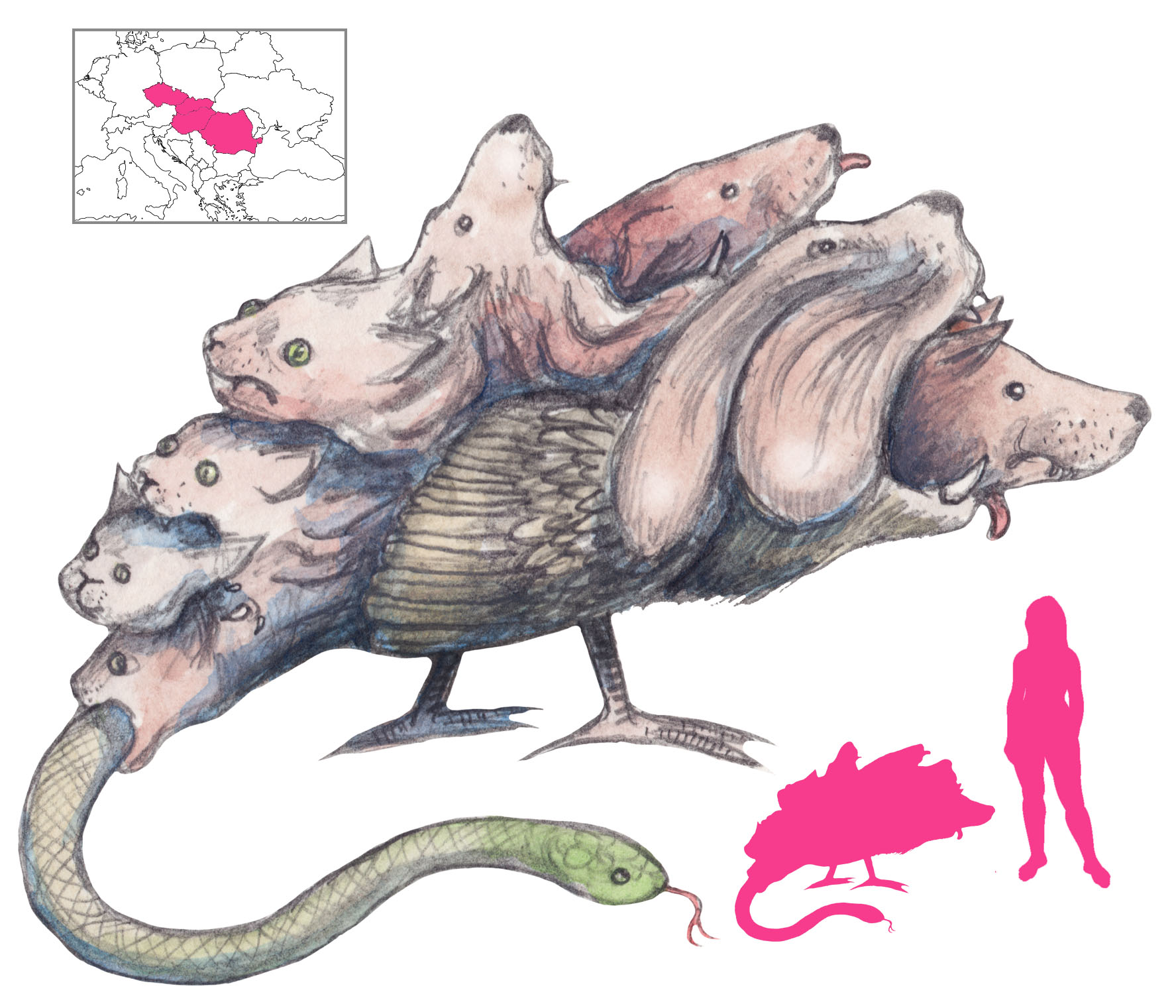

The mere mention of Wakmangganchi Aragondi was enough to strike fear into the bravest warrior – and with good reason. The colossal boar was the biggest and mightiest creature in the world, as tall as a mountain. When standing up, Wakmangganchi Aragondi’s snout touched the Dura Hill, while its tail lay in the Songdu River. It had seven heads emerging from its neck, each head with seven tusks like double-edged scimitars, and each head with a single piercing eye in its forehead glowing like the full moon. On Wakmangganchi Aragondi’s back grew seven clumps of bamboo, seven plots of thatch grass, and seven stalks of bulrushes. Seven perennial streams flowed down its back. The microcosm on Wakmangganchi Aragondi’s back was home to a pair of langurs and their offspring, and seven pairs of moles.

Wakmangganchi Aragondi roamed where it pleased, ate anyone it encountered, and destroyed crops at will. It had a particular fondness for gourds, melons, pumpkins, and yams. Nobody could stop it.

Such was the monster that Goera faced. When the hero-god was born, two more of his uncles went to the market to buy a goat, but they were intercepted and devoured by Wakmangganchi Aragondi. Thus Goera, upon coming of age, decided to destroy this plague that terrified his people.

To fight Wakmangganchi Aragondi, Goera sought the aid of the giant crab Songduni Angkorong Sagalni Damohong. He used it to threaten his grandmother into telling him all she knew about Wakmangganchi Aragondi. He then befriended various supernatural beings, including the progenitors of Steel and Dolomite. From Dygkyl Khongshyl, the smith-god, he obtained a magical two-edged milam sword and a magical bow and arrows that could shatter trees and cure disease. He allied with Tengte Kacha, king of the Elfs, and Maal the dwarf god – both barely two cubits tall, but possessed of great magical powers.

Now fully armed, Goera set out to find Wakmangganchi Aragondi. He found the gigantic boar wallowing in mud, asleep, at Ahnima Gruram Chinima Rangsitram. Goera sent his servant Toajeng Abiljeng to strike the boar from behind and awaken it.

Wakmangganchi Aragondi awoke in fury, and charged Goera. But the hero-god stood his ground and fired a hail of burning darts at it. That was too much for the monster, and Wakmangganchi Aragondi ran for the first time. It galloped east, with Goera in pursuit firing volleys of arrows that lacerated its body. Then Wakmangganchi Aragondi turned north, then back, making wild sallies across the region, making the whole world rumble and quake.

Maddened beyond reason by pain and rage, Wakmangganchi Aragondi tried at last to turn on its tormentor, but Goera avoided its charges by creating piles of rock to climb and hide on. Finally, one of Goera’s maternal uncles in the subterranean region shot an arrow through Wakmangganchi Aragondi’s armpit. The monster staggered and finally collapsed at Ahguara Rongpakmare Shohlyng Janthihol. There Goera decapitated it with a triumphant cry.

The battle had taken seven summers and seven winters. When Wakmangganchi Aragondi was cut open, Goera’s two uncles were found inside, alive but blinded. They recovered their eyesight with time. The meat of Wakmangganchi Aragondi was divided among the people of the area, with the rest left to decompose.

The rock piles created during the battle can still be seen. They are known as Goerani Ronggat, the “Stone Piles of Goera”. Wakmangganchi Aragondi’s droppings are rocks in which seeds can still be seen, and red areas of land are where the monster-boar’s blood was spilled.

References

Bhairav, J. F. and Khanna, R. (2020) Ghosts, Monsters, and Demons of India. Blaft Publications, Chennai.

Rongmuthu, D. S. (1960) The Folk-tales of the Garos. University of Gauhati Department of Publication, Guwahati.