Variations: Physeterus, Physalus, Pistris, Pistrix, Prister. Pristes, Pristis, Capax (“roomy”, referring to its huge mouth), Capidolio (Italy), Mular, Peis Mular (Languedoc), Senedectes, Senedette (Saintonge), Spouter, Whirlpool, Whirl-pool, Whirlepoole

The Physeter, “blower”, Prister, or Whirlpool, is an enormous, monstrous whale. The name, originally associated with a spouting sea monster, has today become the scientific name of the sperm whale or cachalot (Physeter macrocephalus).

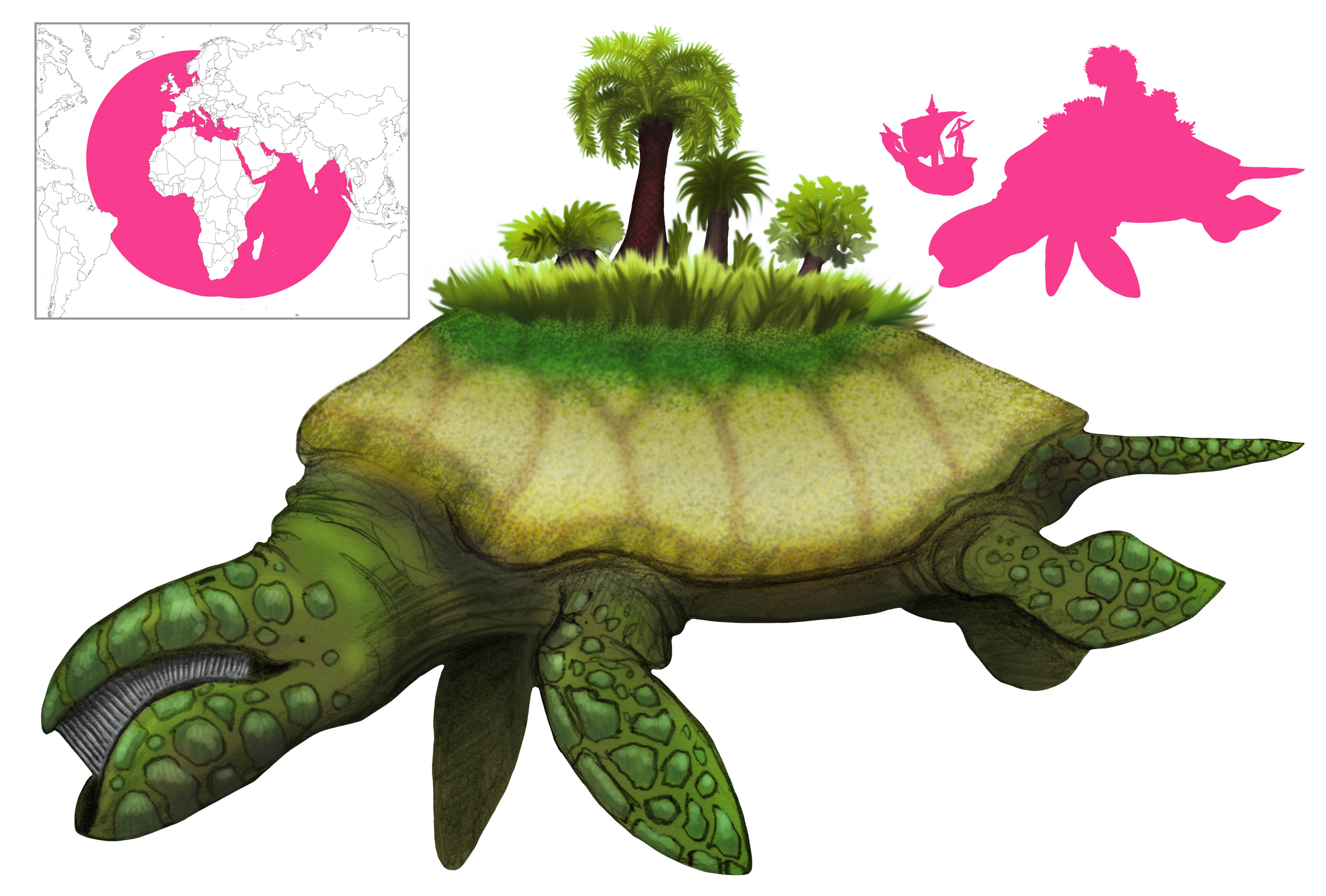

Pliny states that the largest animals in the Indian Sea are the Pristis (shark) and the Balaena (whale). The largest animal in the Ocean of Gaul is the physeter. It lifts itself up like an enormous column, towering higher than the masts of ships, and spouts a flood of water.

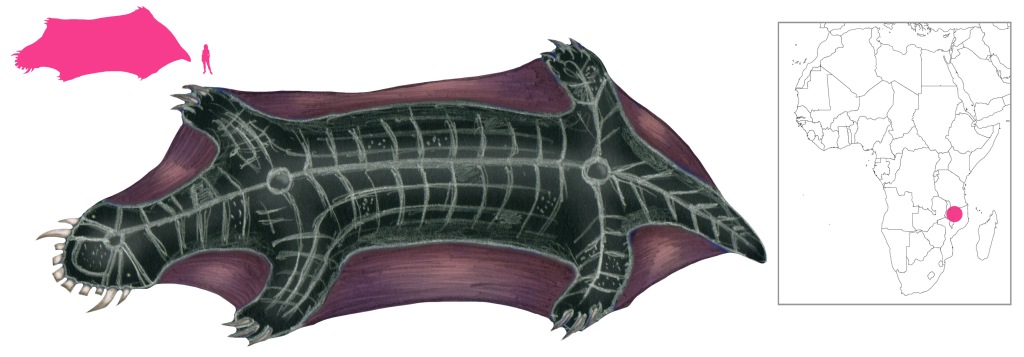

The most notable reference to the physeter as a monster comes from Olaus Magnus. He describes the physeter as two hundred cubits long, with a large, round mouth like that of a lamprey, a tough black hide, and a prehensile tail about 15 or 20 feet wide. It uses its mouth to suck in massive quantities of water which it then spouts violently onto its prey from the blowholes on its head. Its tail can coil around ships and crush them.

Two different images are given by Olaus for the physeter. One is an upright, spouting monster with a horselike head, a gaping, toothless mouth, an erect mane running down its long neck, and a ribbed belly. The other is the tusked, frilled whale which appears in multiple places on the Carta Marina. Münster copies the first version and gives it more canine features, including large fangs and floppy ears; the second he refers to as the trolual or teuffelwal, the “devil-whale”.

Physeters are cruel, malicious creatures that will sink ships for sport. As a physeter’s hide and thick fat are too thick for conventional weapons to penetrate, sailors must resort to other means to ward off the whale’s attentions. One way is to blow trumpets or fire artillery; the loud noises can startle and scare off the physeter. Another is to throw barrels or smaller boats in the path of the whale to distract it.

Rondelet describes the physeter as so named because when it blows it projects a massive amount of water like a mist, which can fill and overturn smaller boats. It is spectacularly large, with a huge mouth, sharp teeth, a large fleshy tongue, and a breathing tract much larger than that of any other animal. It differs from the orca in that it is longer and lacks a fin on its back. One physeter was taken in Italy was placed by the Duke of Florence in front of his palace, but it had to be removed due to its stench. By this point the draconic seahorse of Olaus Magnus has been abandoned; this is the sperm whale as we know it today.

The greatest contribution the physeter has made to literature is in the pages of Rabelais’ epic tale of giants. In Pantagruel, the titular giant and his friends encounter a massive physeter roaring and spouting water, rising higher than the masts of the ship. Panurge immediately wails, comparing it to the Leviathan and the monster that attacked Andromeda, and fears that “it will swallow us all, men and ships, like pills”! But Pantagruel chides him, saying he is better off fearing the horses of the Sun, which snort fire, instead of this monster, which merely blows water. Pantagruel duly peppers the physeter with arrows until it expires and “turned belly up, as do all dead fish”.

De Montfort believed Olaus Magnus’ physeter (apart from the sperm whale) to be a colossal octopus.

References

Aldrovandi, U. (1613) De Piscibus, Libri V. Bologna.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Magnus, O. (1555) Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. Giovanni M. Viotto, Rome.

Magnus, O. (1561) Histoire des pays septentrionaus. Christophle Plantin, Antwerp.

Magnus, O. (1658) A compendious history of the Goths, Swedes, and Vandals, and other Northern nations. J. Streater, London.

de Montfort, P. D. (1801) Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particuliere des Mollusques, Tome Second. F. Dufart, Paris.

Münster, S. (1552) La Cosmographie Universelle. Henry Pierre.

Nigg, J. (2013) Sea Monsters: A Voyage around the World’s Most Beguiling Map. University of Chicago Press.

Pliny; Holland, P. trans. (1847) Pliny’s Natural History. George Barclay, Castle Street, Leicester Square.

Rabelais, F. (1858) Oeuvres de Rabelais, t. II. Firmin Didot Freres, Fils, et Cie, Paris.

Rondelet, G. (1558) L’Histoire Entiere des Poissons. Mace Bonhome, Lyon.

Sainéan, L. (1921) L’histoire naturelle et les branches connexes dans l’oeuvre de Rabelais. E. Champion, Paris.