As part of the Wednesday Interludes, I will also be including paeans to certain creatures I believe are woefully underrated. These will all be fairly modern, pop-culture creatures, and so will not be part of ABC, but I’ll be darned if I don’t give them a deserving moment in the limelight. There will be no particular rhyme or reason to them, but a fair few of them will be from BD (that’s Franco-Belgian comics to you, you uncultured swine), which are less well known in the English-speaking world.

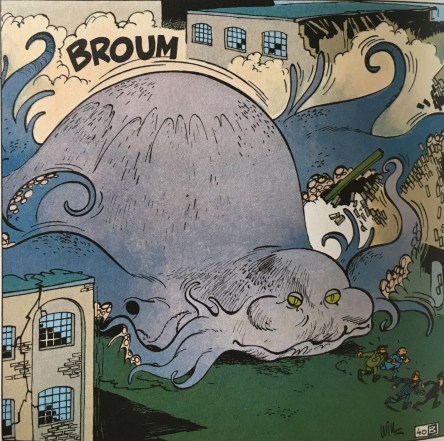

What better way to start than with the nameless Giant Purple Slug? This monster is quite possibly my favorite pop-culture monster of all time, and was responsible for some of the most wonderful, pleasant dreams I had as a child. It is the primary “antagonist” of the 1972 Tif et Tondu book Sorti des Abimes (“Out of the Abyss”, more or less). A bit of background… Tif et Tondu is a Belgian BD by Will and Rosy that follows the adventures of private investigators Tif (the bald guy) and Tondu (the hairy guy, amusingly enough). Their tales fall mostly on the science-fiction side. Today the series is mostly remembered for introducing Monsieur Choc, the urbane, well-dressed, knight-helmeted international criminal mastermind.

But in Sorti des Abimes, it is not Monsieur Choc but a gigantic gastropod that causes consternation for our heroes. The adventure is set in the docks of London, where their friend the Countess Amélie “Kiki” d’Yeu is looking for her confiscated Great Dane. She finds him in a pound, along with something big, tentacley, and drooling green slime. (All art by Will, buy his books!).

The “thing” escapes its confines and slithers into the Thames, where it is sighted swimming through the canals and generally making the most delightful floppery ooshy sounds.

Of course, Our Heroes (O. H.) find out about this and won’t have any of it. I mean, the slug does eat its way through the Thames, chews through a few ship hulls, and drives a steamer aground, but what’s a few fish and ships between friends? Nonetheless, they find out that it’s an abyssal slug brought to the surface by a misguided biologist at the pound. Turns out that, having never seen the light of day, ultraviolet rays cause the slug to grow out of control. O. H. track it down to a dock, where – have I mentioned how much I love/am terrified of the dark outlines of huge things under the water?

The slug is making a water-based beeline for the sea, and crushing everything along its path. After O. H. try to kill it with a WWII-surviving Junkers Stuka (!), the slug decides it’s had enough and hauls its mass out of the water, looking for all the world like an adorable purple cross of Aplysia and Glaucus.

It’s not malicious or anything, it just decides to take a more direct route for the sea – a route that leads it to noted landmark Tower Bridge.

Fortunately for Tower Bridge (what would the Queen say?), O.H. realize that if ultraviolet rays make it grow, infrared rays must clearly have the opposite effect (ignore the spectroscopic and biological problems here, this was a 70s BD). They pelt the poor slug with IR radiation…

… whereupon it melts into black slime.

All it ever wanted was to return to the sea…