Variations: Horned Turban Shell Demon

The Sazae-oni was first formally described by Toriyama Sekien in his first volume on “The Illustrated Horde of Haunted Housewares”. He gives it a philosophical origin, stating that if sparrows become shells and moles become quails, surely it was possible for a sazae – a horned turban shell – to become an oni. So he dreamed.

Reference is made to the 72 Seasons, namely a mid-October season where “sparrows become clams” and a mid-April season where “moles emerge as quails”. The former is based on an old wives’ tale that sparrows become clams to hibernate in winter, while the latter is a poetic description of animals coming out of hibernation.

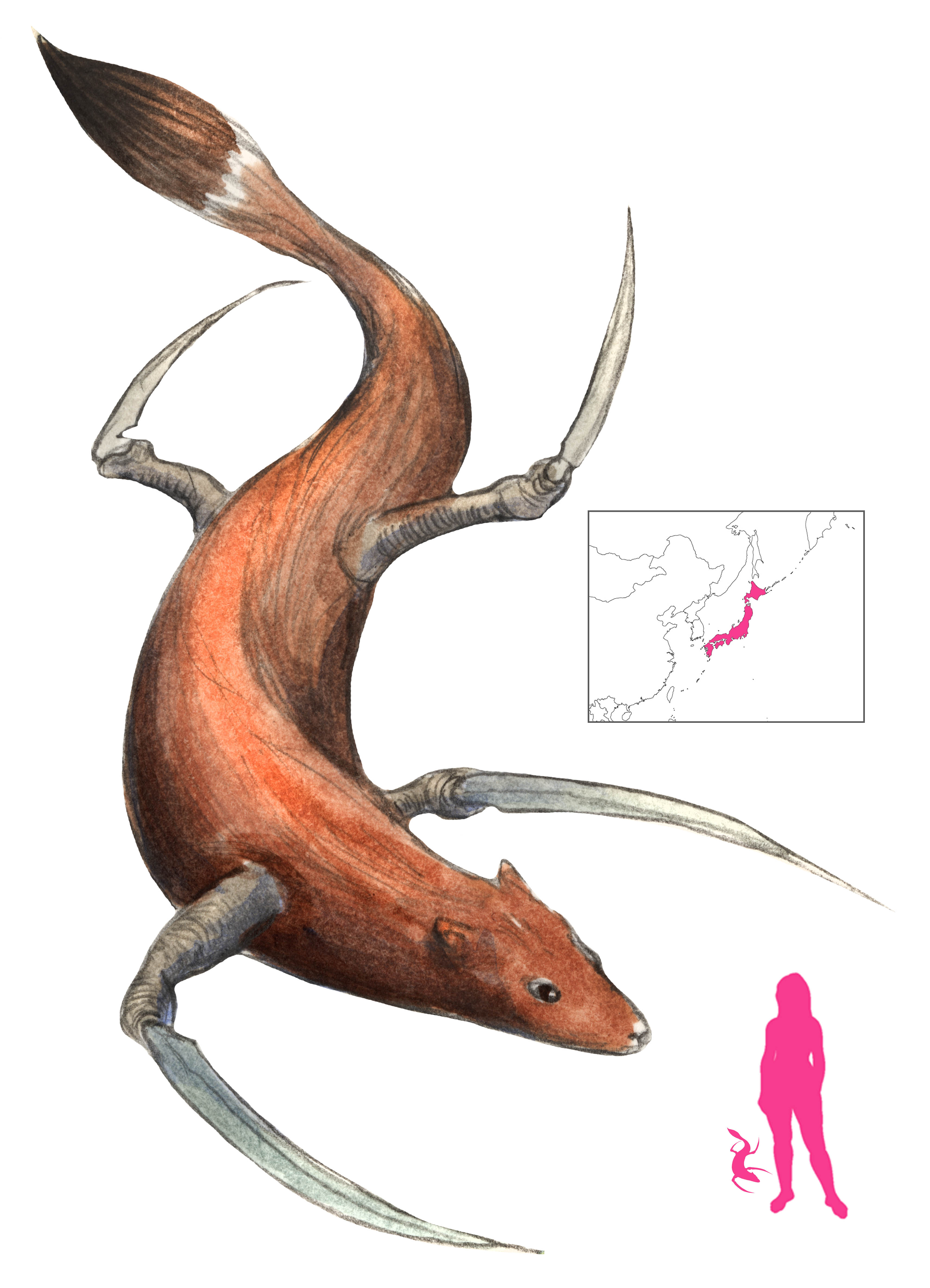

Sekien’s illustration shows a sinuous sluglike creature with humanoid arms emerging from a large horned turban shell. The head is a spiky shell with protruding eyeballs, and seaweed is draped around the neck.

References

Sekien, T.; Alt, M. and Yoda, H. eds. (2017) Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Dover Publications, New York.