Variations: Beste Glapissante; Beste Glatissant, Bête Glatissante, Glatisant Beast; Beste Diverse, Bête Diverse, Diverse Beste, Diverse Beast; Besta Ladrador, Besta Desasemelhada (Portuguese, from the Demanda); Barking Beast, Yelping Beast

The Questing Beast is a creature of many names, sizes, and appearances. Several features, however, are consistent throughout its appearances in Arthurian legend. First, it very noisy, its offspring within its belly baying and yelping constantly. It is also always a portentous creature, but what it symbolizes has varied from author to author. Finally, it is commonly pursued or hunted, whether by knights or by its own offspring within its belly, and often ends up giving birth in the process.

Although “Questing Beast” has been popularized in the English-speaking world by Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, the creature is more commonly known as the Beste Glatissant or Beste Glapissant (in modern French, Bête Glatissante or Bête Glapissante). Glatir or glapir refers to the sound coming from the creature’s belly, a yelping or baying sound like those of hounds chasing prey. This is also the definition of “questing”; a more accurate modern name would be the Yelping Beast or Barking Beast.

The concept of noisy animals in their mother’s womb precedes the Questing Beast. William of Malmesbury describes a dream that was had by King Eadgar. In it, the king sees a pregnant hunting dog lying at his feet. She was silent, but the pups in her womb were barking loudly. This was interpreted as meaning that after King Eadgar’s death, miscreants within his kingdom would bark against the church of God. In the Slavic Twelve Dreams of Sehachi, the titular character dreams of a foal neighing within a mare’s belly, and whelps barking in a dog’s belly; these are interpreted as mothers acting immodestly with their daughters and children rejecting the advice of their parents, respectively.

Another contributor to the genesis of the Questing Beast is the supernatural boar hunt. The most famous examples of those are the boar Twrch Trwyth and the sow Henwen. The latter is even more closely connected to the Questing Beast; like the Beast, Henwen (“Ancient White”) is white in color, and dangerously fecund. Her offspring were to be harmful to Britain, so she was hunted across the country, giving birth along the way to various young. Finally, Henwen disappeared into the sea at Penryn Awstin, similar to the stricken Questing Beast diving into a lake.

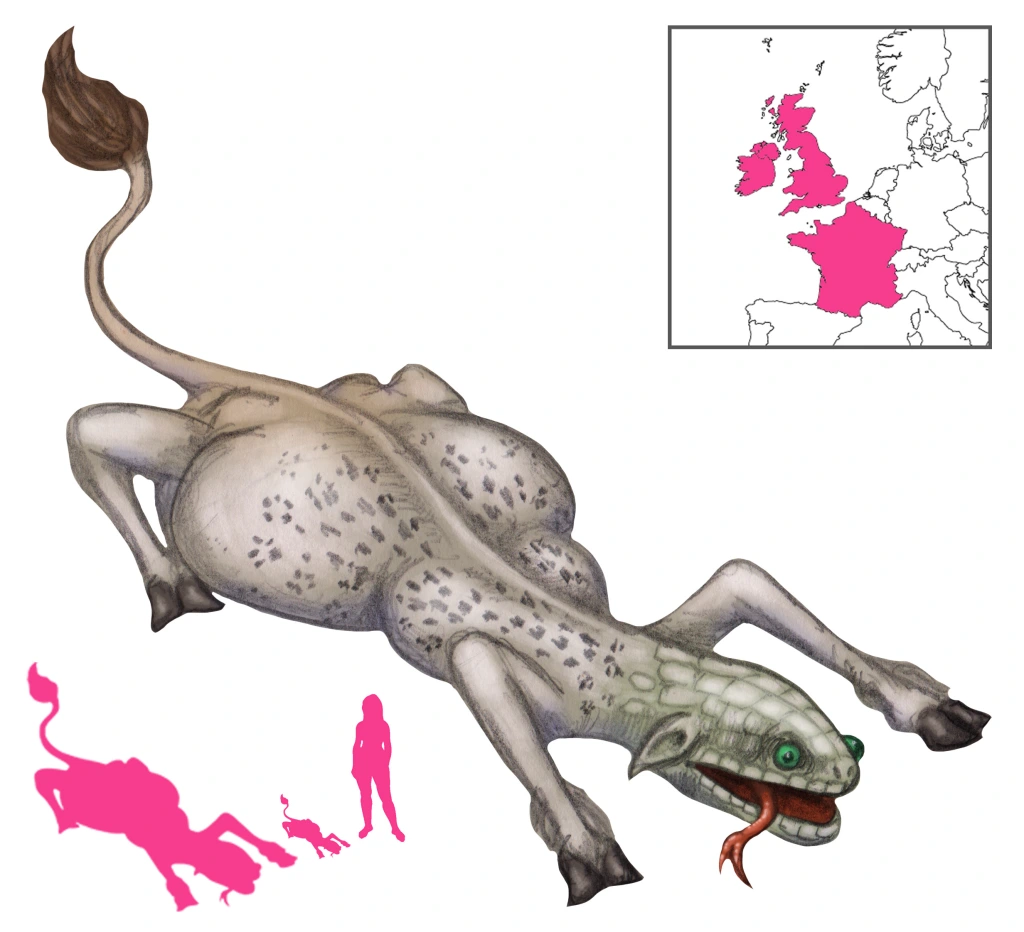

The oldest iterations of the Questing Beast have it encountered by Perceval over the course of his search for the Grail. In the Perlesvaus, Perceval finds a beautiful glade, with a red cross at the center of it. A knight dressed in white is seated at the far end of the glade, with a fair young damsel next to him. Soon a snow-white, emerald-eyed creature, between a fox and a hare in size, enters the glade. The whelps in its womb are barking like hounds, and it is terrified and agitated because of that. Perceval tries to take the small Beast onto his horse, but he is cautioned by the knight, who tells him the Beast has a destiny to fulfill. The Beast runs to the cross, where its twelve young are brought forth. They immediately tear their mother to pieces, but can only devour her head. Upon doing so, they go mad and scatter into the forest. King Pelles later explains the significance of the creature to Perceval: it represents Jesus Christ, and the twelve hounds that killed it and scattered are the twelve tribes of Israel, following the prevalent Christian belief of the time.

Gerbert de Montreuil’s continuation of Perceval borrows from the Perlesvaus. We are not given a description of the Beast, but are instead told that it is grant a merveille (“marvelously large”). The Beast’s young are barking and yelping from within its belly, and when it comes up to the cross in the glade, they emerge violently, breaking it in two pieces. The young then devour their mother before going mad, turning on and killing each other. This bloody episode has a far more mundane meaning – Perceval is told that the loud, murderous whelps are the people who disturb church services by talking loudly and complaining about hunger!

In the Estoire du Saint Graal, there is a Beste Diverse (“Diverse Beast”) found beside a cross. No mention is made of its yelping, but it is white as snow, and has the head and neck of an ewe, the legs of a dog, black thighs, the body of a fox, and the tail of a lion. In the prose Merlin, the Diverse Beste or Beste Diverse sounds like 30 or 40 baying hounds and is moult grant (“very big”). Perceval is destined to hunt it.

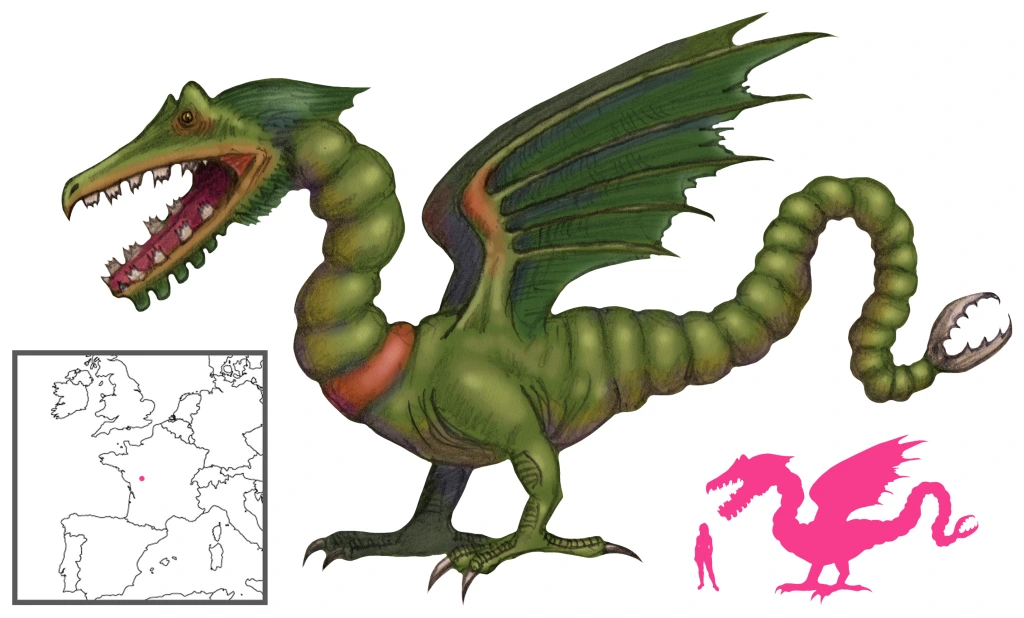

In the prose Tristan, the Beste Glatissant has the legs of a stag, the thighs and tail of a lion, the body of a leopard, and the head of a snake; its yelping is equal to that of a hundred hunting hounds. The addition of snake, leopard, and lion elements grant it unsavory connotations; the combination of lion and leopard is reminiscent of the Beast of the Apocalypse, and a snake or dragon is always inauspicious.

No longer a creature of purity torn apart by its own offspring, the Questing Beast is now an evil, wretched being spawned from violence. Its mother was the daughter of King Ypomenes, who lusted for her brother. When she could not have him, she instead turned to a devil, who slept with her and convinced her to accuse her brother of attempting to rape her. He was duly sentenced to be torn apart by dogs. As he died, the brother proclaimed that his sister would give birth to a monster, one from whose belly the barking of dogs would forever remind others of his shameful death. As predicted, the daughter gave birth to the Questing Beast, and she was executed for her crimes.

The Saracen knight Palamides had particular reason to hate the Questing Beast, as its horrid shriek had killed eleven of his twelve brothers. In the Portuguese Demanda, the Questing Beast is finally slain during the last years of the Grail quest, when Palamides strikes it and it runs into a lake that immediately starts to boil. The lake has since then become known as the Lake of the Beast.

Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, the foremost mention of the Questing Beast in English literature, follows the prose Tristan in its description. The Questing Beast is said to have a head like a serpent’s, a body like a leopard’s, buttocks like a lion’s, and feet like a hart. Its belly made a noise like thirty couple hounds barking. King Arthur first sees the Questing Beast after an illicit tryst with the wife of King Lot of Orkney. Arthur had stopped to rest by a well when the Questing Beast, making a horrid din, came up to drink from it. As it drank, the noise coming from its belly was quelled, but it started up against as soon as the creature had finished and ran off. Arthur then encountered Sir Pellinore, who hunted the Questing Beast. After Pellinore’s death, the task of hunting the Questing Beast was passed on to Sir Palamides.

Merlin later revealed to Arthur the significance of the Questing Beast. The king had seen the beast because he, too, had just done something unforgivable. The wife of King Lot was in fact his sister on his mother’s side, and the child of this adulterous and incestuous union – Mordred – was destined to destroy Arthur’s kingdom.

References

Evans, S. (1903) The High History of the Holy Graal. J. M. Dent & Co., London.

Gaster, M. (1900) The Twelve Dreams of Sehachi. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, pp. 623-635.

Löseth, E. (1891) Le Roman en Prose de Tristan, analyse critique. Emile Bouillon, Paris.

Malory, T. (1956) Le Morte d’Arthur, v. I. J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London.

Malory, T. (1956) Le Morte d’Arthur, v. II. J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London.

Nitze, W. A. (1902) The Old French Grail Romance Perlesvaus, A Study of its Principal Sources. John Murphy Company, Baltimore.

Nitze, W. A. (1936) The Beste Glatissant in Arthurian Romance. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie, 56, pp. 409-418.

Paris, G. and Ulrich, J. (1886) Merlin: Roman en Prose du XIIIe Siècle, t. I. Librairie de Firmin Didot et Cie., Paris.

Pickford, C. E. (1959) L’evolution du Roman Arthurien en Prose vers la Fin du Moyen Age. A. G. Nizet, Paris.

Williams, M. (1925) Gerbert de Montreuil: La Continuation de Perceval, t. II. Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris.