Variations: Mokéle-mbêmbe, Mokele Mbembe, Monstrous Animal; Nsanga; Emela-ntouka, Emia-ntouka, Aseka-moke, Ngamba-namae, Killer of Elephants, Water Elephant; Nguma-monene, Badigui, Ngakoula Ngou, Diba, Songo; Mbielu-mbielu-mbielu

Tales of the Mokele-mbembe, “One Who Stops the Flow of Rivers” (or, more simply, “River-Shutter”), come from the Congo River Basin, around the Ikelemba, Sanga, and Ubangi rivers and Lake Tele. It is the most discussed and well-known of the “African mystery beasts” primarily due to the cryptozoological interpretation that defines it as a surviving sauropod dinosaur. It – or its unnamed predecessor, at any rate – was initially described as hailing from Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

There is nothing unique about the mokele-mbembe. It is at least four notable mythic creatures: the river-shutter, the pachyderm slayer, the unicorn, and the giant reptile. River-shutters are sub-Saharan creatures with an aptitude for withholding or releasing a river’s water; in communities dependent on life-giving water, this can mean the difference between life and death. The pachyderm slayer – a creature so mighty and dangerous that it routinely kills the biggest and scariest animals known – is a far broader category that has been famously applied to the dragon and the unicorn. The presence of a single horn is a recurring feature of monsters, most notably the unicorn. Finally, giant reptiles (often irresponsibly called “dragons”) are a worldwide theme.

The first to suggest the existence of a large dinosaurian creature was big-game hunter and zoo supplier Carl Hagenbeck. Hagenbeck reports a huge animal, half elephant and half dragon, from deep within Rhodesia (not the Congo, where the mokele-mbembe eventually took up residence). He said that there are drawings of it on Central African caves but provides no further detail on that angle. All in all it is “seemingly akin to the brontosaurus [sic]”. Hans Schomburgk, one of Hagenbeck’s sources, stated that the lack of hippos on Lake Bangweulu was due to a large animal that killed hippos. An expedition sent by Hagenbeck to investigate the creature’s existence found nothing. Tantalizing as it may be, the entire episode with the nameless saurian is no more than an aside in Hagenbeck’s book, an attempt to attract potential investors by capitalizing on the contemporary “dinomania” sweeping the globe.

The first decade of the twentieth century saw a vast increase in public interest in dinosaurs. In 1905 the mounted skeleton of Apatosaurus was unveiled at the American Museum of Natural History and London’s Natural History Museum inaugurated its Diplodocus. Soon museums across the world were receiving their own gigantic sauropod skeletons courtesy of Andrew Carnegie, industrialist and patron of the sciences. In 1907 the skeletons of enormous sauropods emerged in German East Africa; these eventually formed a hall of titans in Berlin’s Natural History Museum. Hagenbeck’s account of a living sauropod was not written in a vacuum, but was – consciously or not – drawing on contemporary massive interest in massive reptiles.

E. C. Chubb of the Rhodesia Museum dismissed Hagenbeck’s claim. To him, this creature was no more than another example of the “land edition of the Great Sea Serpent”. He received further accounts of the Rhodesian creature, a large beast with flippers, rhinoceros horns, a crocodile’s head, a python’s neck, a hippo’s body, and a crocodile’s tail; a three-horned creature from Lake Bangweulu, Zambia, that killed hippos.

The next step came with Lieutenant Paul Graetz in 1911. He wrote about the Nsanga of Lake Bangweulu, a “degenerate saurian” like a crocodile but without scales and armed with claws on its feet. Graetz supposedly came by strips of nsanga skin but saw nothing more tangible.

The account that concretized the mokele-mbembe and gave it its name was that of German officer Ludwig Freiherr von Stein zu Lausnitz. His report places the mystery beast firmly in the Congo, around the Likouala rivers. The mokele-mbembe has smooth, brownish-grey skin. It is approximately the size of an elephant, or a hippopotamus at the smallest. Its neck is long and flexible. It has only one tooth, but that tooth is very long; “some say it is a horn” adds Stein (this feature is usually ignored, as it does not conform to the sauropod narrative). It has a long, muscular tail like a crocodile’s. It attacks canoes and kills its occupants without eating them. The mokele-mbembe is vegetarian and it feeds on a type of liana, leaving the water to do so. It lives in caves dug out by the sharp bends in the river. Stein was shown a supposed mokele-mbembe trackway but could not make it out among the elephant and hippo tracks.

Stein’s account is the basis for the modern mokele-mbembe legend. The report was never officially published, but was publicized by Willy Ley (who inexplicably linked the mokele-mbembe to the dragon of the Ishtar Gate).

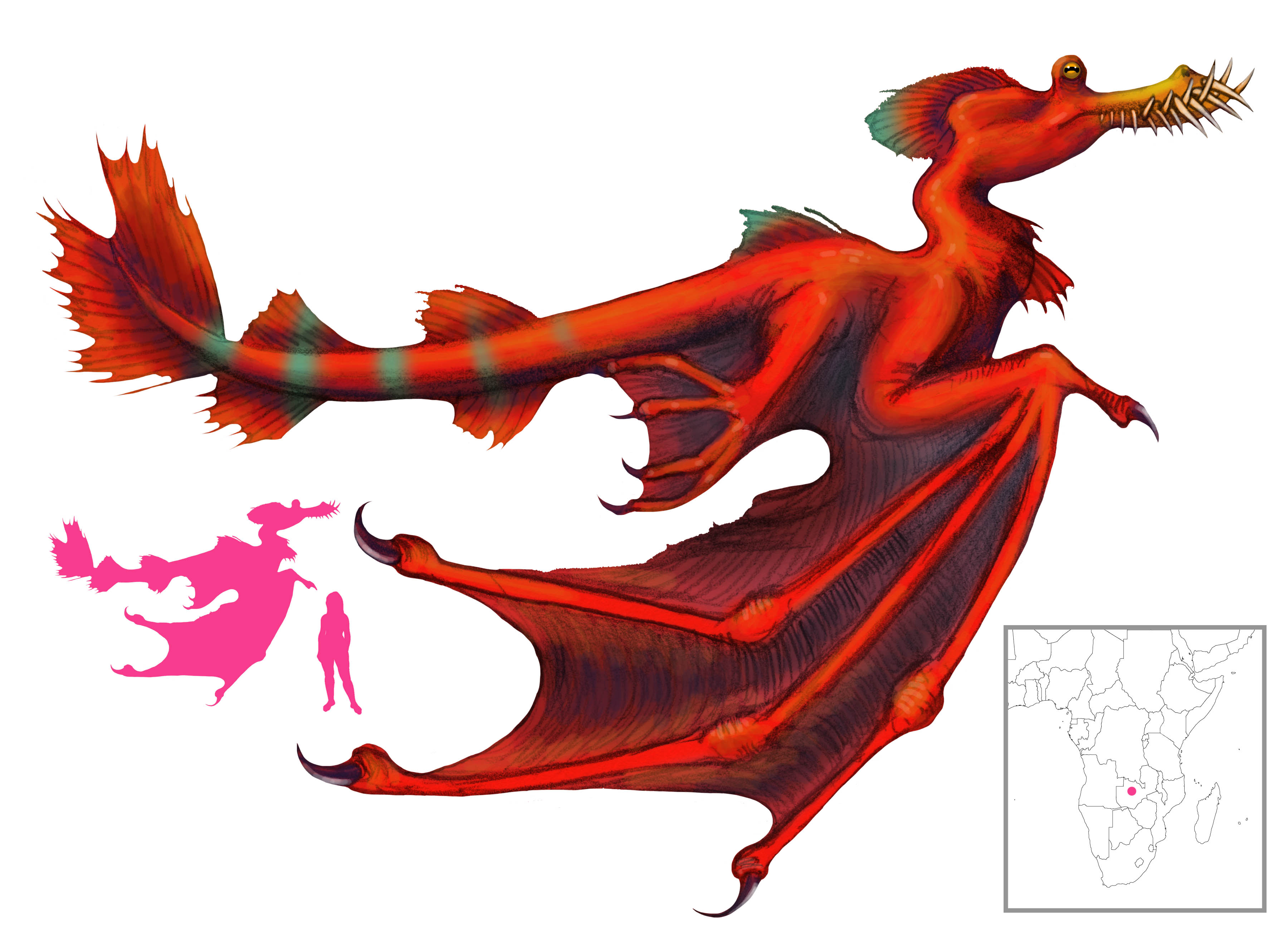

This in turn led to successive expeditions to the Congo by James H. Powell Jr. and Roy Mackal. Mackal determined the mokele-mbembe to be 5 to 10 meters long, most of which is neck and tail. It has smooth brown-grey skin and a very long neck with a snakelike head on the end. Sometimes there is a frill, like a rooster’s comb, on the back of the head. The legs are short and stout, with three claws on the hind legs, and leave 30-centimeter-wide prints. The malombo plant is the staple of the creature’s diet. While herbivorous, the mokele-mbembe is very aggressive and will destroy any canoes that approach it. It does so by tipping the vessels, then biting and lashing out with its tail.

In addition to the mokele-mbembe, Mackal is responsible for bringing to light a whole menagerie of prehistoric survivors and some unusually-sized modern reptiles as well. The Emela-ntouka, for instance, is larger than an elephant. Its skin is smooth, hairless, and wrinkly, brown to grey in color. Its legs are thick and columnar to support its weight. The tail is heavy and similar to a crocodile’s. There is a single horn on the front of the head. These creatures are herbivorous and kill buffaloes and elephants by goring them with their single horns. If all this sounds familiar, it’s because none of it is distinguishable from what has been said about the mokele-mbembe (including the horn, no longer an inconvenient detail). Mackal optimistically proposes that the emela-ntouka is a late-surviving ceratopsian dinosaur.

Nguma-monene, “large python” (from nguma, “python”, and monene, “large”) is reported from the Dongou-Mataba river area. It is a large, serpentine reptile, some 40 to 60 meters long, with a saw-toothed ridge down its back. The head is snake-like with a forked tongue that flicks in and out. It is greyish-brown like just about every other large reptilian cryptid. It is indistinguishable from the badigui, ngakoula ngou, diba, or songo of the Ubangi-Shari. All of these are giant snakes which kill hippos and browse on tree branches without leaving the water. They leave tracks behind like those of a lorry. All of them are indistinguishable from the mokele-mbembe. Mackal describes them as enormous monitor lizards.

The Mbielu-mbielu-mbielu, or “animal with planks growing out of its back”, is restricted to the Likouala-aux-Herbes in the Congo. It is known solely as a large animal that has large “planks” on its back with algae growing between them. The rest of its appearance is unknown. Only one informant reported the mbielu-mbielu-mbielu. Mackal makes a surviving stegosaur out of it.

Finally there is the Ndendecki (a giant turtle), the Mahamba (a giant crocodile), and the Ngoima (a giant eagle). None of these are any more believable than the mokele-mbembe and its host of synonyms.

It would be tedious to list all subsequent expeditions (all unsuccessful) or the anthropological procedures used (all unprofessional). It should however be noted that the hunt for the mokele-mbembe has been coopted by the creationist movement. For some reason these people have decided that the discovery of the mokele-mbembe will be enough to destroy the entire theory of evolution (it won’t) because a surviving dinosaur would be a lethal paradox to science (it isn’t).

There is nothing unique about the mokele-mbembe, but as a vaguely defined reptilian river-shutter it is a sort of Rorschach test that viewers can project their preconceptions onto. Far from a detailed local legend, the myth of the mokele-mbembe evolved to suit the needs of the visitors who sought it, whether zoo suppliers, colonialists, cryptozoologists, or creationists. Any underlying folklore about river-shutting reptiles has long been abandoned and discarded, relegated to an etymological footnote. It does not fit the narrative.

References

Hagenbeck, C., Elliot, S. R. and Thacker, A. G. trans. (1911) Beasts and Men. Longmans, Green, And Co., London.

Ley, W. (1959) Exotic Zoology. The Viking Press, New York.

Loxton, D. and Prothero, D. R. (2013) Abominable Science! Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and other Famous Cryptids. Columbia University Press, New York.

Mackal, R. (1987) A living dinosaur? E. J. Brill, New York.

Naish, D. (2016) Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; and Osmolska, H. (2004) The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. University of California Press, Berkeley.