Variations: Korokottas, Krokottas, Krokottos, Krokouttas (Greek); Corocottas, Crocotta, Crocote, Crocuta (Latin); Cynolycus, Kunolykos, Kynolykos (Greek, “Dog-wolf”); Leoncerote; Chaus; Cameleopard (Strabo); Cyrocrothes, Leucrocotham (Albertus Magnus); Cirotrochea (Ortus Sanitatis); Hyena, Iena, Yena, Yenna

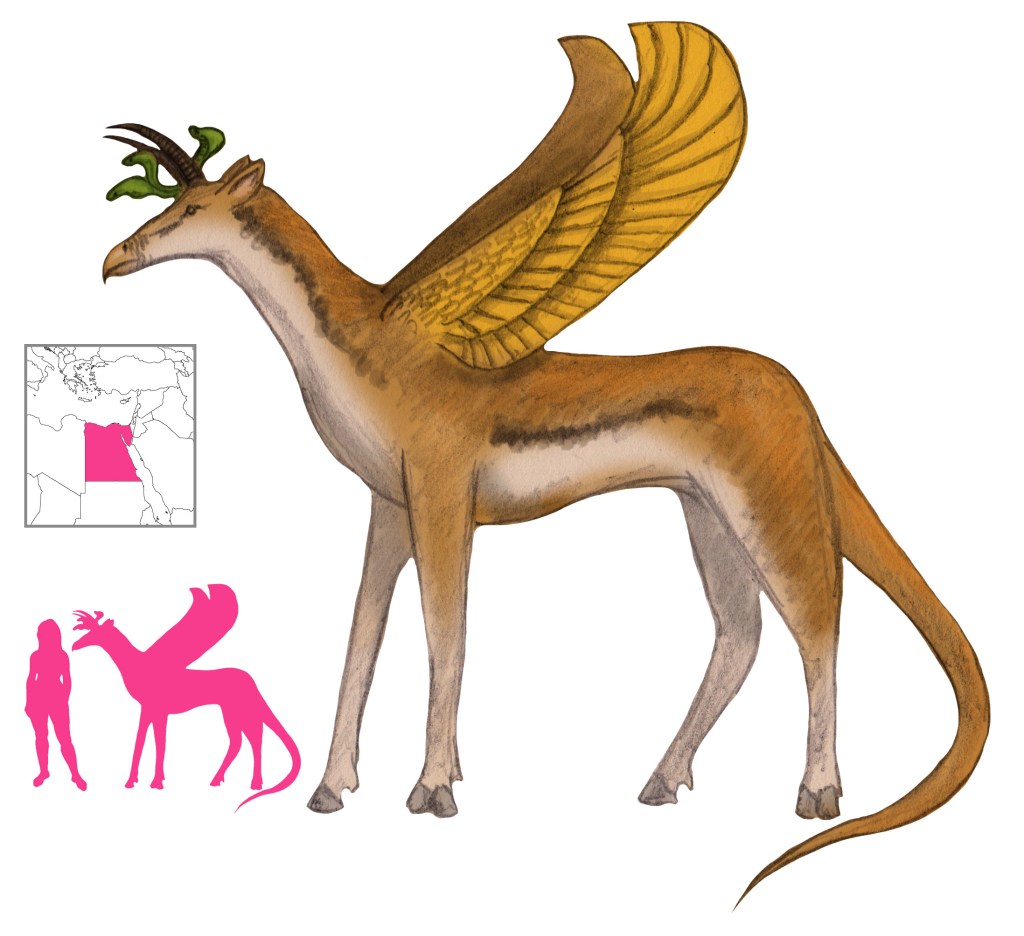

The hyena was known to the ancients under several names. The term hyaina (Greek) and hyaena (Latin) almost certainly refer to the smaller and more familiar striped hyena. The more exotic Corocotta is probably the spotted hyena, especially considering its vocal qualities and prowess at hunting. Then there are other terms that may refer to hyenas such as the glanos, the chaus, and the thōs, the last of which is probably a jackal, civet, or hunting dog.

Much of what is said about the corocotta is shared with the hyena, and even Greek and Roman authors seem uncertain as to whether or not it is seprate from the hyena. Translators of classical texts have also chosen to retain “corocotta” as a unique word, or simply replace it with hyena. Further muddying the waters is the emergence of the derivative leucrocotta, which gained features of the hyena/corocotta through this confusion and passed on its own features (such as a lion-hyena ancestry and single bones for teeth) to the corocotta.

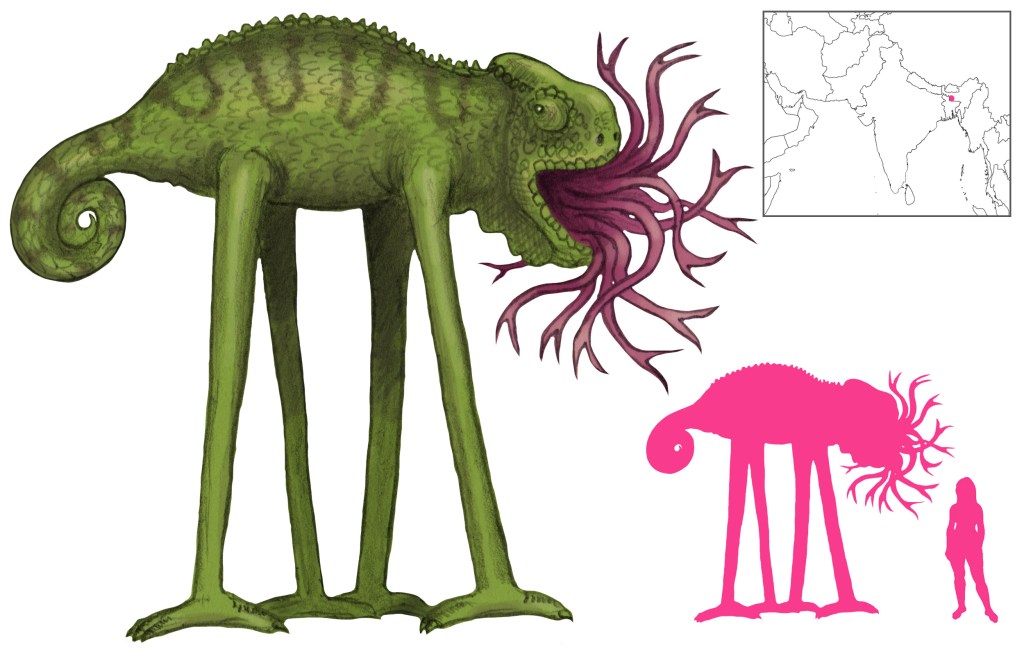

What is known is that the corocotta is unfamiliar, hailing from far-flung lands – either Ethiopia or India, depending on the author (the regions were used interchangeably). If it is indeed African, the word corocotta may be a Libyan or Ethiopian word for the hyena. Lassen (cited by McCrindle) saw in Ctesias an Indian origin to the corocotta, and derives its name from the Sanskrit kroshtuka, “jackal”. The name has since then been applied to the spotted hyena Crocuta crocuta.

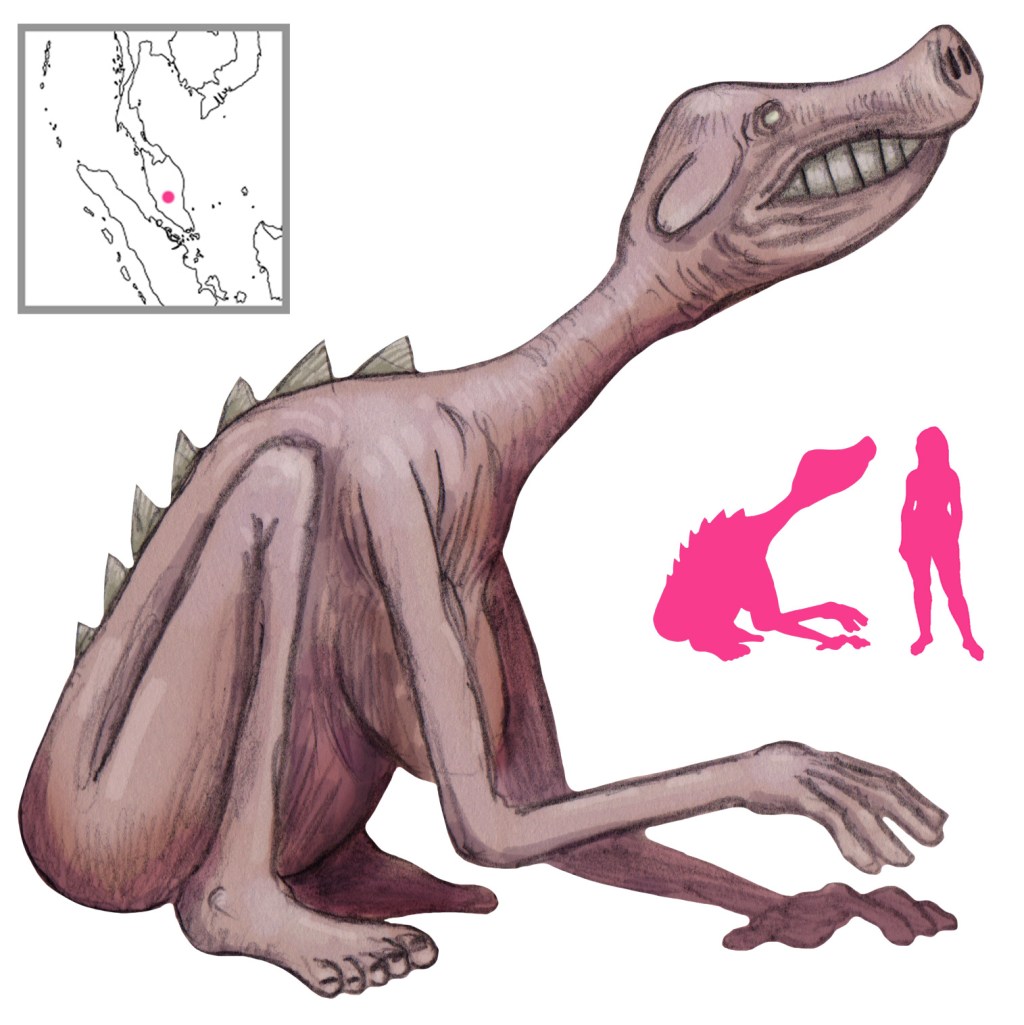

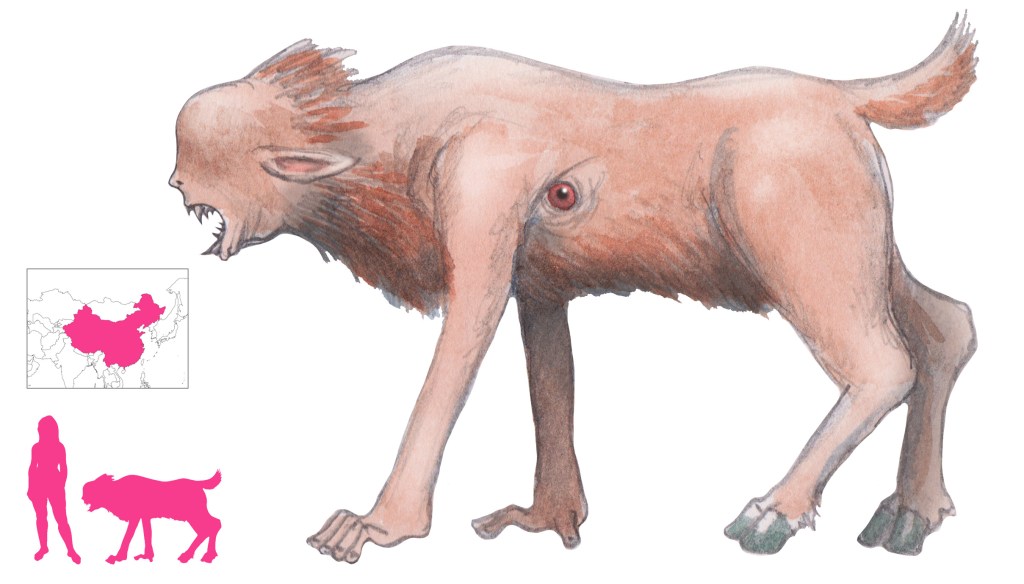

Ctesias says that the corocotta is also known as the cynolycus (“dog-wolf”). It is found in Ethiopia and is incredibly strong. It can mimic human voices, calling people out by name at night and killing them when they come out in response. It is as brave as a lion, as fast as a horse, as strong as a bull, and cannot be fought with steel weapons.

Agatharchides says it is a fierce and powerful creature that lives in Ethiopia. It can crush bones with its jaws. The corocotta can also mimic human speech, and it uses this ability to lure humans out at night so it can kill them. Agatharchides rejects this.

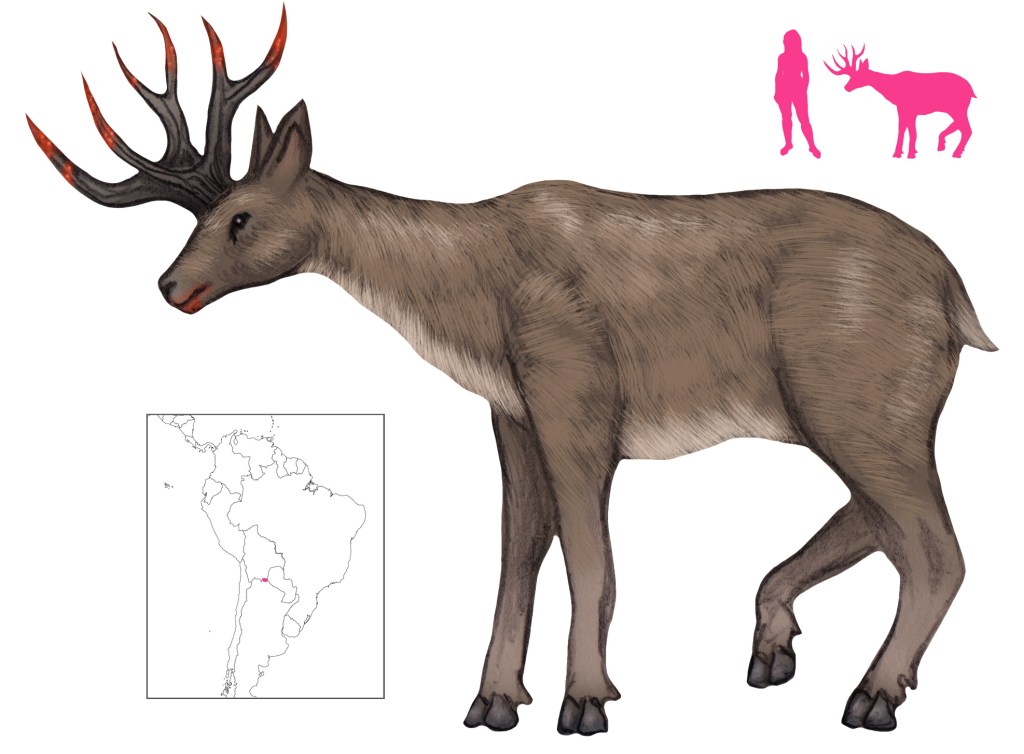

Pliny says that the corocotta is the offspring of a dog and a wolf. It can crush anything with its teeth, and anything it eats is immediately digested and passed through its body. It is Ethiopian. Elsewhere further powers are attributed to the hyena or crocuta: it changes sex every other year, its neck is an extension of its spine, it can imitate human speech and vomiting sounds, it digs up graves, its shadow strikes dogs dumb, it paralyzes other living things by circling around them three times, and it has a thousand variations in eye color.

Aelian separates the hyena and the corocotta. The hyena roams around cattle pens by night and imitates the sound of vomiting, attracting dogs which are promptly killed and eaten. But the corocotta is even craftier. Aelian says that it listens to woodcutters calling each other by name and the words they say, then it imitates their voices, calling out to its victim and withdrawing before calling again. It continues this game of cat-and-mouse until its prey has been tempted far away from their friends, whereupon the corocotta pounces and kills them. Aelian admits that “the story may be fabulous”.

Dio Cassius reports that Severius had a corocotta imported from India to be slain in the games in AD 202. It had never been seen in Rome before.

By the time the crocotta and leucrocotta had reached medieval Europe, the similarity of their descriptions, combined with the leucrocotta’s more memorable physical features, caused them to combine. The MS Bodley 764 bestiary adds a mention of the crocote at the end of the hyena entry, describing it as a hybrid of lion and hyena with a single bone replacing its teeth (both features of the leucrocotta). It imitates human voices and is always found in the same place. The leucrota, on the other hand, is given a complete entry of its own which is fairly faithful to its original account.

Albertus Magnus refers to the “cyrocrothes”, which is the corocotta with the single tooth-bone of the leucrocotta, and the “leucrocotham”. It is further corrupted in the Ortus Sanitatis, which includes both the “cirotrochea” and the “leucrocuta”.

Topsell divides his Hyena entry to cover the varieties of hyena. In addition to the hyena proper, he provides additional hyenas including the papio (baboon), the mantichora, and the crocuta. The crocuta has become the same as the leucrocuta; it is an Ethiopian cross between a lioness and a hyena, with its teeth replaced by a single bone in each jaw. It imitates men’s voices and can break and digest anything.

Ludolphus is clear that the hyena or crocuta (by now they are one and the same, and refer to what we would now call the spotted hyena) is the most voracious of all Ethiopian beasts, preying upon men in the day as well as at night, and digging down the walls of houses and stables. It is speckled with black and white spots.

It may be that the hyena of the ancients was the striped hyena, while the corocotta was the spotted hyena, or vice versa. The imitation of human speech seems a clear allusion to the spotted or laughing hyena’s vocalizations. Despite that, the Palestrina Nile Mosaic identifies a striped creature as a corocotta; spotted animals are labeled as examples of the mysterious thōs.

Finally, a notable Spanish bandit was known as Corocotta. This may be a complete coincidence.

References

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. II. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ball, V. (1885) On the Identification of the Animals and Plants of India. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, II(6), pp 302-346

Barber, R. (1993) Bestiary. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge.

Borges, J. L.; trans. di Giovanni, N. T. (2002) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Vintage Classics, Random House, London.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Brottman, M. (2012) Hyena. Reaktion Books, London.

Ctesias, McCrindle, J. W. trans. (1882) Ancient India as described by Ktesias the Knidian. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta; B. E. S. Press, Bombay; Trubner and Co., London.

Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Ludolphus, J. (1684) A New History of Ethiopia. Samuel Smith, London.

Magnus, A. (1920) De Animalibus Libri XXVI. Aschendorffschen Verlagbuchhandlung, Münster.

Pliny; Holland, P. trans. (1847) Pliny’s Natural History. George Barclay, Castle Street, Leicester Square.Robin, P. A. (1936) Animal Lore in English Literature. John Murray, London.

Topsell, E. (1658) The History of Four-footed Beasts. E. Cotes, London.

Unknown. (1538) Ortus Sanitatis. Joannes de Cereto de Tridino.