Variations: Chonchon, Chonchoñ, Chon Chón, Chuncho, Chucho, Chuchu, Chaihue; Chonchones (pl.); Cocorote, Corocote (Venezuela); Cuscungo (Ecuador); Tecolote, Telocote (Mexico)

The Chonchón is a bird of ill omen from Chile and Argentina; it originally hails from Araucanian Mapuche folklore. Chonchón is also the name of a kind of kite.

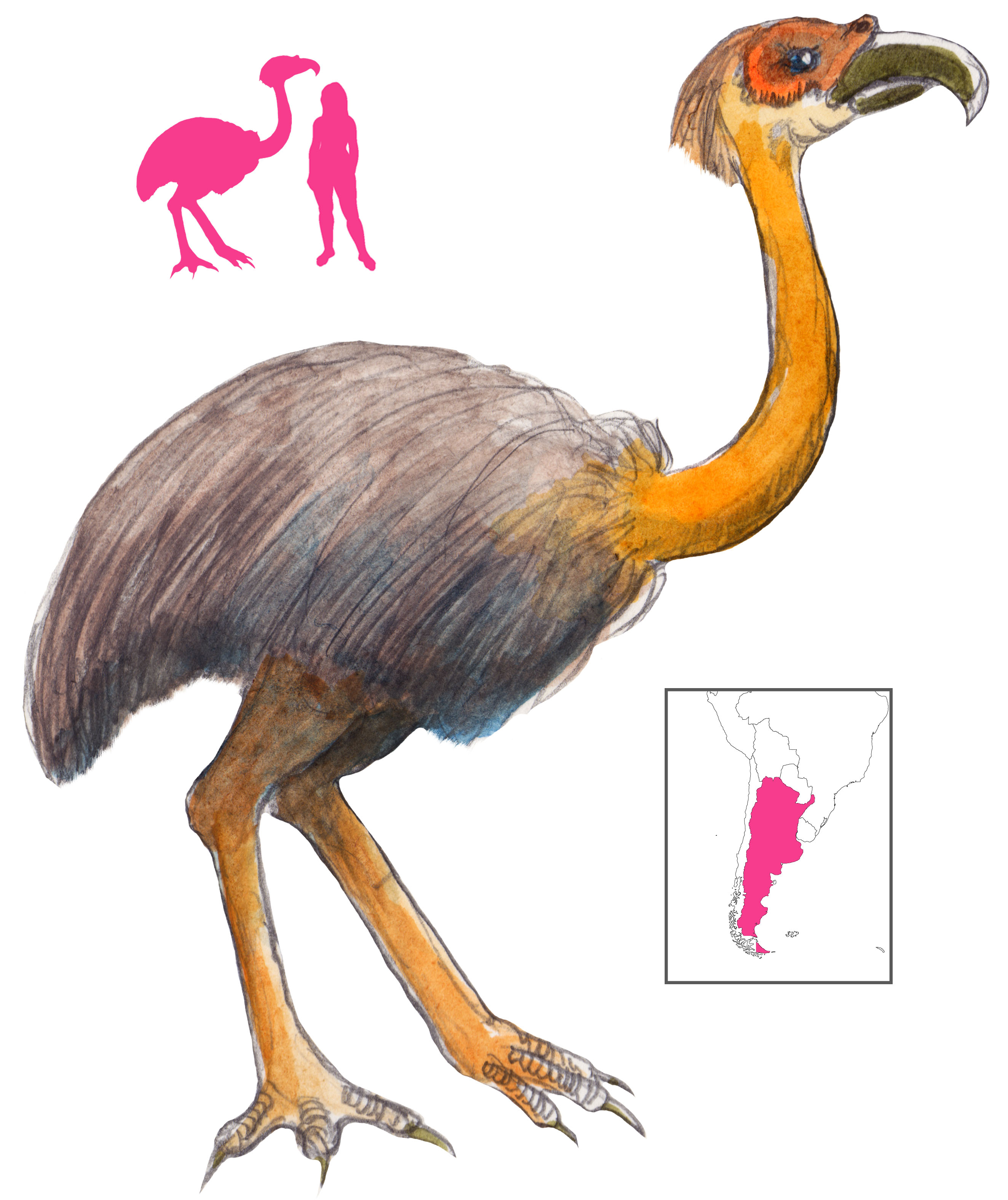

In its simplest form it is a bird of the night, an owl (Strix rufipes) that flies on silent wings during the night to announce illness, death, or some other unwelcome event. When its croaking is heard it is advised to throw ash into the air and utter a few prayers in the hopes of turning away its evil.

The chonchón is also said to be a calcu or evil sorcerer in disguise. It resemble a human head, with oversized wing-like ears that allow it to fly. During the night, these sorcerers’ heads detach themselves from their bodies and fly around to cause mischief, invisible to most, their ominous tué, tué, tué call announcing misfortune. They have the same powers as sorcerers do, and have been known to suck the blood of sleepers.

In order to repel chonchones, several methods are recommended. These include drawing a Solomon’s seal on the ground, laying out a waistcoat in a specified manner, or reciting certain phrases or hymns such as the Magnificat, the Doce Palabras Redobladas, “Saint Cyprian goes up, Saint Cyprian goes down, Saint Cyprian goes to the mountain, Saint Cyprian goes to the valley”, or “Jesus goes ahead, follow him behind”. Doing any of these actions forces the chonchón to leave, or even fall to the ground where it can be destroyed. If the headless body of a chonchón sorcerer is found, turning it onto its stomach prevents the chonchón from returning to it. Finally, a more humane means of dealing with a chonchón is to yell “Come back tomorrow for some salt!” The next day, the chonchón in its human guise will show up and sheepishly request the promised salt. Except perhaps for the last method, most interference with the ways of chonchones will eventually incur the revenge of the chonchón or its friends.

One chonchón was reportedly grounded in Limache when someone made a Solomon’s seal, causing a large bird with red wattles to fall out of the sky. It was decapitated and its head fed to a dog, whose belly swelled up as though it had eaten a human head. Later the local gravedigger told that unknown persons had come to bury a headless body.

Not all chonchones are irredeemably evil, however. A Mapuche man in Galvarino once woke up early in the morning to find his wife’s body without her head. He immediately realized that she was a chonchón, and turned the body onto its stomach to prevent the head from reattaching. As expected, a chonchón soon flew heavily into the house, flapping and staggering as though blind. It then turned into a dog and whined pleadingly to be reunited with its body. The man took pity on it and allowed it to do so, and it became his wife once more. “Every night I leave, without you knowing, and visit distant lands”, she explained. She begged him not to tell anyone, and swore she would never harm him, and both kept their word; the story became known only after the wife died of natural causes.

Some authorities separate the chonchón from the chuncho, with the former being the sorcerous flying head and the latter the owl. Their calls are also different, with the chuncho hooting chun, chun, chun. They have further owl equivalents in the Venezuelan cocorote, the Ecuadorian cuscungos, and the Mexican tecolote. It is also compared to the myth of the voladora, a witch who flies while cackling loudly.

All this is quite unfair to the owls themselves, which benefit the farmers by eating mice, rats, and other vermin.

References

Aguirre, S. M. (2003) Mitos de Chile. Random House, Editorial Sudamericana Chilena.

Borges, J. L.; trans. di Giovanni, N. T. (1969) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Clarke, Irwin, & Co., Toronto.

Cifuentes, J. V. (1947) Mitos y supersticiones (3rd Ed.). Editorial Nascimento, Santiago, Chile.

Coluccio, F. and Coluccio, S. (2006) Diccionario Folklórico Argentino. Corregidor, Buenos Aires.

Rodríguez, Z. (1875) Diccionario de Chilenismos. El Independiente, Santiago.

Soustelle, G. and Soustelle, J. (1938) Folklore Chilien. Institut International de Coopération Intellectuelle, Paris.