Mammoth thanks to Schnellegeister Hexenwolf for sharing Mansi Mythology with me and making this entry possible!

Variations: Witkəś-ōkja (male), Witkəś-ēkwa (female); Witkul’, Witkul’-ōkja (male), Witkul’-ēkwa (female)

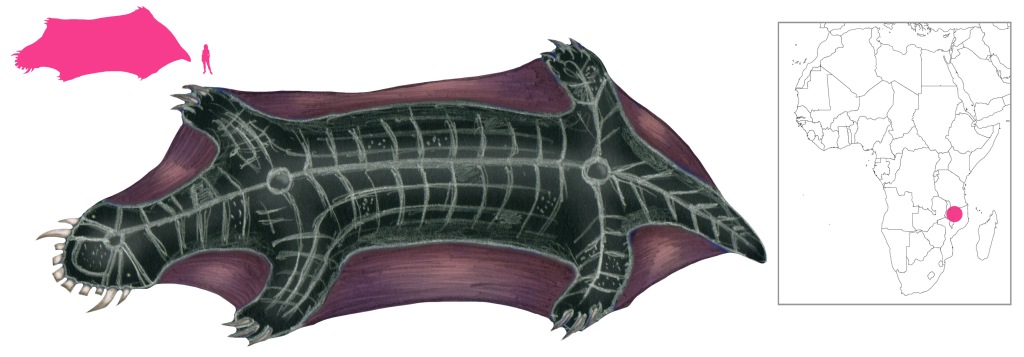

The Witkəś is a creature from the mythology of the Mansi people of Russia. It is one of the few mythical creatures unquestionably derived from paleontological evidence – in this case, from the remains of woolly mammoths. Witkul’ is a synonym, apparently related to locality – witkul’ are found in lakes, and witkəś in rivers.

The name of the witkəś or witkul’ is derived from wit, “water”. A witkəś lives in the depths of the water, as evidenced by the location of mammoth tusks and bones on riverbanks. The tusks were believed to be antlers, shed by the witkəś much like reindeer and elk do. Since there are witkəś bones in evidence, the witkəś themselves are believed to be mortal creatures that avoid contact with humans. Their shapes are undefined, with some traditions anthropomorphizing them, dividing them into male witkəś-ōkja and female witkəś-ēkwa. They have been known to invite guests underwater to drink tea.

Along the Sos’va River it was believed that old bears and elks would gorge themselves on earth, then sink into the water to become water spirits. In lakes they would become witkul’, while in rivers they became witkəś.

The witkəś and witkul’ are tireless diggers, excavating holes and river channels to direct the course of the water. A witkul’-ēkwa was believed to have dug out the Lyapin River, and a witkul’-ōkja made the big lakes of the Sos’va River. On the other hand, the witkəś on the Tavda River would pull horses into the water, and its appearance was an omen of impending death.

Nobody fishes in lakes where witkul’ live. Even birds fly around them. Any living creature that comes near may be pulled in. A witkəś can be found in every whirlpool in a river, and they enjoy drowning anyone who enters their domain. One way to scare off or kill a witkəś is to fill a boat with salt, pitch, and gunpowder, and set up a scarecrow decoy for good measure before setting the boat on fire and pushing it out to the whirlpool to be swallowed. The witkəś will be fatally maimed by the explosive boat, and when its dying groans are heard, that is when it is safe to return to the water.

Around Berezovo it was traditional to sacrifice a reindeer to the witkəś at the time the ice began to drift, tossing the skin, bones, and blood of the animal into the whirlpool. Elsewhere items such as copper cauldrons would be tossed into whirlpools as offerings to the witkəś. Once an old man stole a silk handkerchief with silver coins that was meant for the witkəś. His boat was immobilized, and a witkəś over ten meters long appeared, accusing the man of theft. The kerchief was thrown into the water, and the boat began moving again immediately.

References

Napolskikh, V., Hoppál, M., and Siikala, A. (2008) Mansi Mythology. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest.