I am indebted to Fredrik “Tektalox” Hansing for introducing me to and translating material related to this enormous esocid!

Variations: Trollgäddor (pl.); Jättegädda (Giant Pike); Krongädda (Crown Pike); Skällgädda (Bell Pike); Sjörå

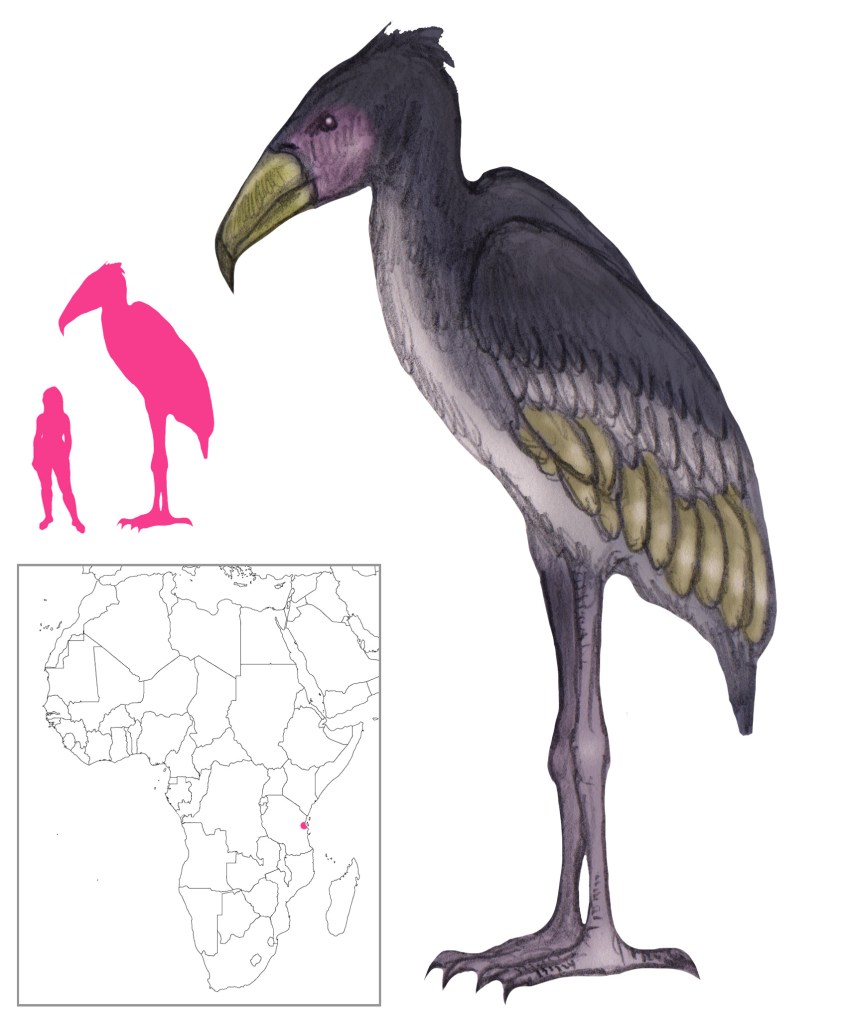

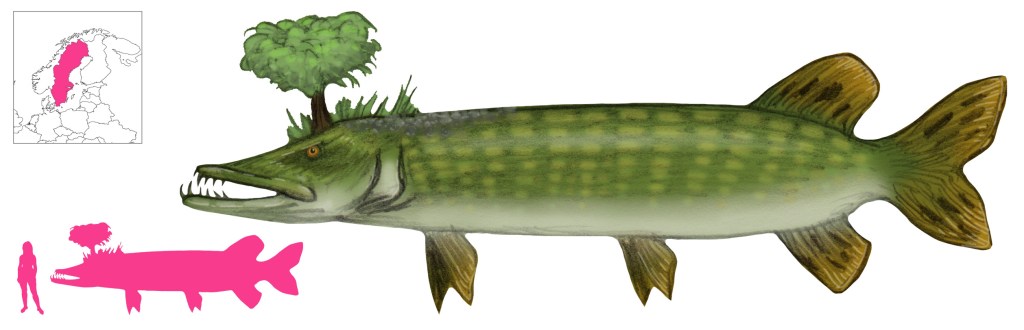

The lakes and waterways of Sweden are home to Trollgäddor, “troll pike”. These variable supernatural creatures take the form of a large pike, and cause problems ranging from being nuisances to attacking people.

Sometimes the pikes are associated with the Sjörå, the Mistress of the Lake; some may even be Sjörå themselves. More frequently they are the pets of the Sjörå. The water-spirit dresses them up with bells like cows, and the fish are called skällgäddor or “bell pikes”. Anglers who return those pikes upon capture are rewarded with success at fishing; those who kill them incur the Mistress’ wrath and find their livestock dying off.

The krongädda or “crown pike” is another of the Sjörå’s pets. It is a pike with a crown, and is regarded to be the Sjörå’s prized possession. The exact nature of the “crown” is unclear. It has been suggested that the crown is actually the remains of a bird’s talons embedded in the fish’s skull, left behind by an unfortunate osprey drowned by its “catch”.

Other times the trollgädda’s appears as a normal pike with no distinguishing characteristics. A pike captured in Lake Odensjön was large enough, but as the angler returned home it grew heavier and heavier. By the time he entered the house he had to drop it, and it started thrashing about as it grew big enough to destroy the house. Fortunately the angler had the presence of mind to let it out; the fish squirmed and flopped its way back into the water and disappeared.

Trollgädda tales vary by locale. The Kvittinge pike kills a human every year. In Lake Mjörn there is a huge, hairy, and bearded pike tied up with an iron chain. In Skåne there are pikes as big as wooden beams. The Dalsland pike has eyes as big as saucers and scales as big as roof tiles. It barely fits in the coves, and seeing it is a clear sign that fishing will be futile.

The pike of Lake Bolmen is as long as the lake is wide, and can barely move. It is so big that its back looks like a rocky island, and so old that a willow shrub grows on its head and neck. An enterprising angler tried to catch the pike using a rope for a fishing line and a dead foal for bait. When the trollgädda bit, the angler fastened the rope to a lakeside barn and went to get help. They returned to find the barn dragged out into the lake.

References

Gustavsson, P. (2008) Laskiga vidunder och sallsamma djur. Alfabeta, Stockholm.

Hansing, F. (pers. comm.)

Svanberg, I. (2000) Havsrattor, kuttluckor och rabboxar. Bokforlaget Arena, Falth & Hassler, Smedjebacken.