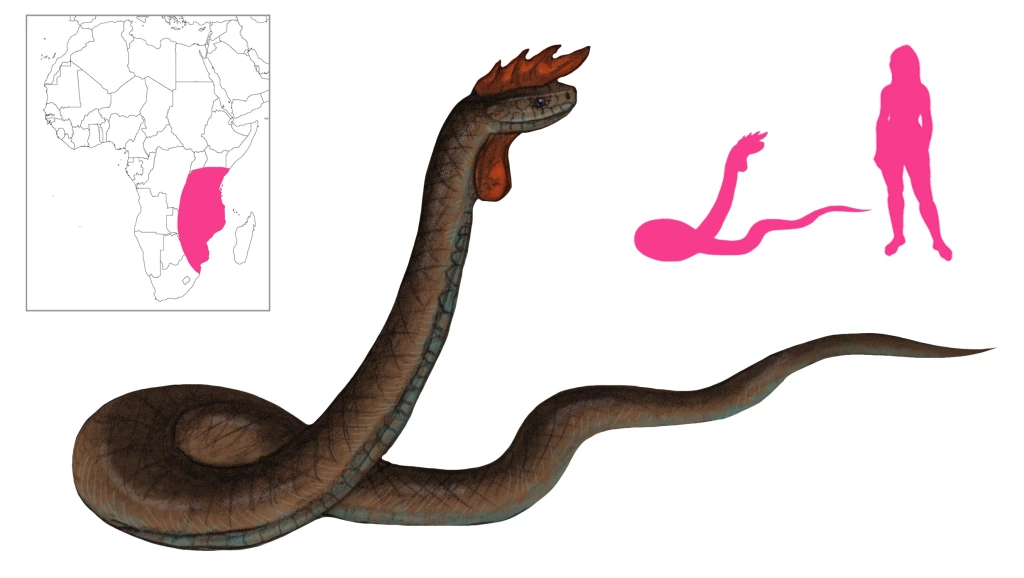

Variations: Njoka Tambala (Malawi); Bubu (Shupanga, Mozambique); Hongo (Ngindo); Indlondlo (Zulu); Inkhomi (“Killer”, Nyakyusa); Kovoko (Nyamwezi); Limba (Chitipa District, Malawi); Nguluka (Chitipa District, Malawi); Ngoshe (Bemba); Noga-putsane (“Goat-snake”, Botswana); Songo, Songwe (Yao); Black Mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis

Crowing Crested Cobra is a blanket term used for a number of crested, noise-making venomous snakes. It is one of the most widespread legends in East African folklore, and it is also known from the West Indies, especially Jamaica and Santo Domingo.

A crowing crested cobra is a snake similar to a cobra with a crest on its head and capable of making sounds like a rooster. Those sounds range from crowing to clear bell-like notes to bleating. Sometimes wattles are present as well. The snake is venomous and very dangerous.

Livingstone reported the death of a little girl in Mozambique caused by an enormous snake that dashed at the child, bit her, and made off into a hole. This snake was known as Bubu to the people of the area, and they describe it as twelve feet long, dark with a dirty blue color under its belly, and with red markings on its head like the wattles of a rooster. It will hide in a tree and strike passers-by one after the other, killing them in short order. To protect against it, a pot of boiling water or porridge should be carried on the head. The snake will try to bite that and kill itself in the process, or at least get scalded and discouraged from future attempts. Nonetheless, Livingstone admits that one “will probably recognize the Mamba in this snake”. He also makes separate mention of another, different snake that makes a sound like the crowing of a cockerel, adding that “this is well authenticated”.

Shircore claimed to have in his possession the bony skeleton of the fleshy comb as well as part of the neck with some vertebrae in it, five lumbar vertebrae, and a single 22-mm by 16-mm dorsal vertebra from a very large snake. He describes the crowing crested cobra as growing 18 to 20 feet long. It is buff-colored, with a red crest that points forward. The male has wattles as well. There is no hood like a cobra’s. The head is small for the size of the body, while the bones of the skull are denser than usual. It moves very fast and can climb trees. The male crows like a rooster, while the female clucks, te te te te. Both sexes make a warning sound, chu chu chu chu, repeated rapidly. Shircore also attributes to the crowing crested cobra or Inkhomi a diet of maggots, explaining that it kills indiscriminately to create more food for maggots. It is tolerated around villages, where mutual respect keeps it and humans apart. It is also intimately associated with sorcery and witchcraft; chieftains and witch doctors wear pieces of it, and parts of its body are used in curative preparations. Parts of the snake in mixtures amplify the potion’s effects. Shircore gives it a range of the lower Zambezi in the South to Victoria Nyanza in the North, Lake Tanganyika in the West, and the Indian Ocean in the East.

Loveridge equates the crowing crested cobra with the black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis). Tellingly, he also gives songo and songwe as the native names of the black mamba – and Shircore also gives songo as the name of the crowing crested cobra.

Similarly vocal snakes are found throughout East Africa. The Limba of Malawi is crested and crows. It can be found in the Mafinga Ridge. The fierce Nguluka has the head of a snake on the body of a guineafowl. Noga-putsane, the “goat snake” or “serpent of a kid”, bleats like a goat to attract its victims. Livingstone claimed to have heard one calling from a spot where no kid could have been. The Zulu plumed viper Indlondlo is also known to bleat. Finally, even the umdlebe or dead man’s tree, said to kill anyone that approaches it and strike birds dead in flight, is said to bleat like a goat!

Rationalizations for the combinations of features include a snake trying to eat a loudly protesting rooster, and a snake that was sloughing its skin, with pieces of dead skin giving the impression of a crest and wattles around the head. The snake and rooster are strongly involved in voodoo belief, which give a cultural background to the creature. The resemblance to the basilisk is also notable.

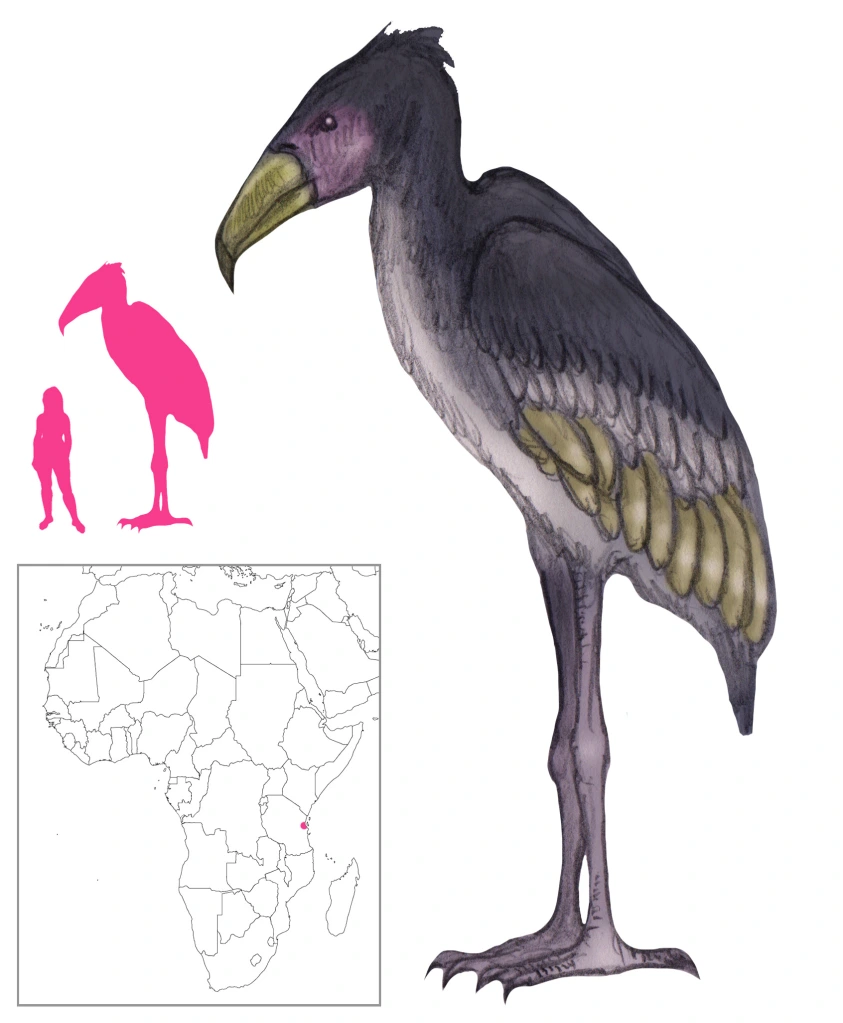

Calls attributed to the crowing crested cobra are usually the work of rails. These are small, retiring birds with a tendency to call at dusk or at night. Flufftails in particular have particularly haunting calls. The call of the buff-spotted flufftail (Sarothrura elegans) has been connected to the crowing crested cobra, as well as to banshees, to a chameleon giving birth, to a chameleon mourning for its mother which it accidentally killed in a squabble over mushrooms, and to giant snails.

References

Collins, W. B. (1959) The Perpetual Forest. J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadephia.

Hargreaves, B. J. (1984) Mythical and Real Snakes of Chitipa District. The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 40-52.

Hichens, W. (1937) African Mystery Beasts. Discovery (Dec): 369-373.

del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; and Sargatal, J. (eds.) (1996) Handbook of the Birds of the World vol. 3. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Livingstone, D. (1857) Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. John Murray, London.

Loveridge, A. (1953) Zoological Results of a Fifth Expedition to East Africa III: Reptiles from Nyasaland and Tete. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, 110(3), pp. 143-322.

Parker, H. W. (1963) Snakes of the World. Dover Publications, New York.

Shircore, J. O. (1944) Two Notes on the Crowing Crested Cobra. African Affairs, 43(173), pp. 183-186.

Stuart, C. and Stuart, T. (1999) Birds of Africa. The MIT Press, Cambridge.

Waller, H. W. (1874) The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, v. II. John Murray, London.