Variations: Ahune, Ahunum, Hahanc, Hahane, Hahune, Hahanie, Channa, Cestreus, Fastaroz, Mullet, Swam-fisk, Swamfisck, Swamfysck, Svvamfysck

The long journey of the Ahuna begins in Aristotle, where the cestreus (mullet) is described as the most greedy of all fish, with a frequently distended abdomen. It is edible only when its belly is empty. When threatened it hides its head, convinced that its whole body is hidden that way. In the same sentence Aristotle then mentions the sinodon (dentex) that is carnivorous and eats squid, and the following sentence deals with the channa (grouper) that lacks an oesophagus and whose mouth opens directly into its stomach.

Michael Scot’s translation from the Arabic gives fastaroz for the mullet, theaidoz for dentex, and hahanie for grouper. He also mistranslates the phrase “the dentex is carnivorous and eats squid”, instead assuming that the adjective “carnivorous” applies to the previously-mentioned mullet – not only that, but it becomes self-carnivorous. Now the mullet hides its head when frightened, and consumes itself. Another lapse creates the hahune or ahuna, which exists only as a comparison to the mullet (“the mullet is more voracious than the other fishes and especially that which is known as ahuna”).

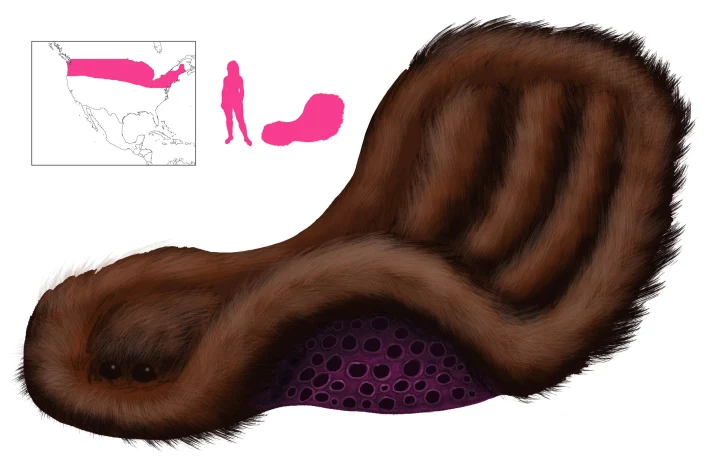

By the time Cantimpré compiled his bestiary, mullet, dentex, and grouper were all combined into one creature, the ahuna or hahuna. This sea monster is highly voracious and will feed until its belly swells beyond the size of its own body. Its mouth connects directly to its stomach; in fact, it has no neck or stomach to speak of. When attacked it tucks its head and limbs away in its body like a hedgehog, folding its skin and tissues over itself. It will remain like this until the danger goes away. If hunger strikes while the ahuna is curled up, it will be forced to eat part of itself to assuage its insatiable gluttony.

We are not given any physical description of the ahuna besides its chubbiness. One of Cantimpré’s depictions gives it an avian beak and horizontal wavy stripes; the Ortus Sanitatis, on the other hand, makes the ahuna a literal sea-hedgehog, complete with a curly tail.

The swamfisk described by Olaus Magnus appears off the coast of Norway and otherwise follows the exact description given by Cantimpré. It is much less common than cetaceans and is frequently hunted for its fat and oil, used primarily for treating leather and providing light during the long winter months. If Olaus Magnus was plagiarizing wholesale, the name he uses is unique.

De Montfort, unaware of its origins, believed the swamfisk to be a giant octopus.

References

Aristotle, Cresswell, R. trans. (1862) Aristotle’s History of Animals. Henry G. Bohn, London.

de Cantimpré, T. (1280) Liber de natura rerum. Bibliothèque municipale de Valenciennes.

Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris.

Gauvin, B.; Jacquemard, C.; and Lucas-Avenel, M. (2013) L’auctoritas de Thomas de Cantimpré en matière ichtyologique (Vincent de Beauvais, Albert le Grand, l’Hortus sanitatis). Kentron, 29, pp. 69-108.

Magnus, A. (1920) De Animalibus Libri XXVI. Aschendorffschen Verlagbuchhandlung, Münster.

Magnus, O. (1555) Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. Giovanni M. Viotto, Rome.

Magnus, O. (1561) Histoire des pays septentrionaus. Christophle Plantin, Antwerp.

de Montfort, P. D. (1801) Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particuliere des Mollusques, Tome Second. F. Dufart, Paris.

Swan, J. (1643) Speculum Mundi. Roger Daniel, Cambridge.

Unknown. (1538) Ortus Sanitatis. Joannes de Cereto de Tridino.