Variations: Each-uisge, Water horse

While the kelpie plies the rivers and streams of Scotland, the lochs and seas are home to the far more dangerous Each Uisge, literally the “Water Horse”. Each uisges are carnivorous, and relish human flesh. While other water-horses are content with playing pranks, tossing riders into ponds and laughing at their lot, an each uisge’s actions are always predatory. In addition to hunting humans, they will also reproduce with farm animals, siring foals with flashing eyes, strong limbs, distended nostrils, and an indomitable spirit.

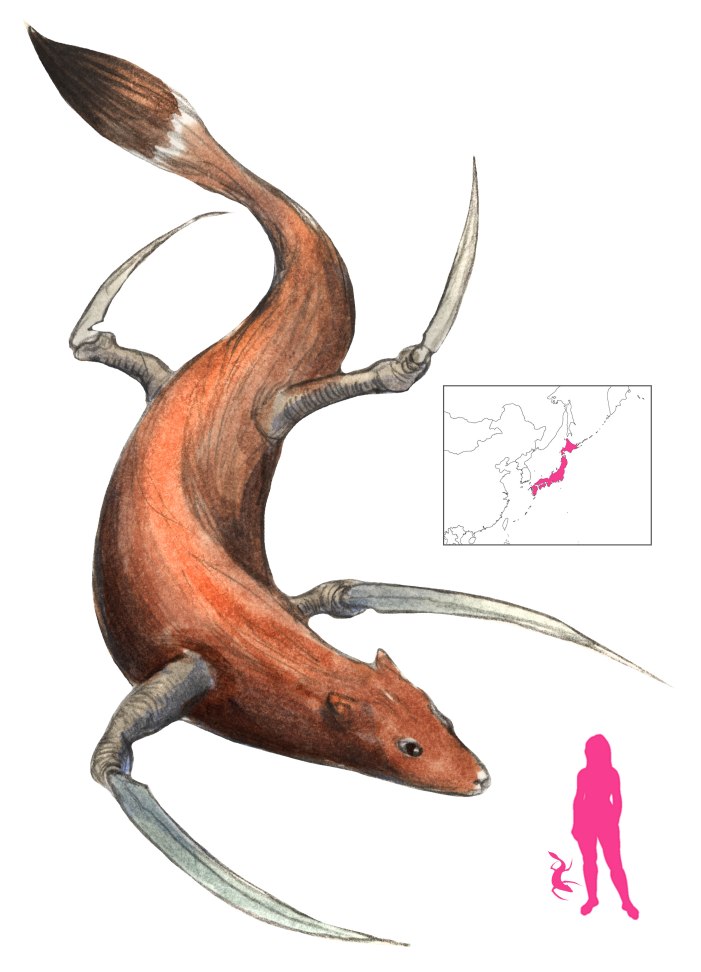

Like kelpies, each uisges are shapeshifters and can assume a wide variety of forms, from sea life to attractive human beings. Their most common guise, however, is that of a fine horse, standing by the waterside and waiting to be mounted. Such horses are always magnificent, sleek, and wild-looking, and their neighs can wake people up all around the mountains.

The each uisge in human form is attractive and charming, but always has some features that give it away – horse’s hooves, for instance, or hair full of sand and seaweed, or a tendency to whinny in pain. In such cases where an each uisge lover was found out, it is usually killed by the girl’s father or brothers before it can devour her. Regardless of the shape it has taken, an each uisge’s carcass will turn into formless jellyfish slime by the next day.

Sometimes the each uisge is a large bird, although this may be confusing it with the boobrie. More worrisome features have been observed, including viciously hooked, 17-inch long beaks, enormous claws, and footprints larger than an elephant’s. An each uisge observed at the Isle of Arran was light grey, with a parrot-like beak and a body longer than an elephant’s.

For all their carnivorous nature, each uisges can be easily tamed by slipping a cow’s cap or shackle onto it, turning it docile and harmless. If the cap or shackle ever falls off, the each uisge immediately gallops off for the safety of the loch, possibly dragging its would-be master with it. Each uisges can also be tamed by stealing their magic bridles. They use them to see fairies and demons, and are vulnerable without them. Finally, like many other evil creatures, each uisges avoid crosses and other religious symbols.

Every loch in Scotland has its own each uisge. Loch Treig was said to have the fiercest each uisges. Loch Eigheach means “Horse Loch” and is home to a much-feared each uisge, with a deadly charm and a silky grey hide. It would yell triumphantly as it bore its prey into the water.

Seven girls and a boy once found an each uisge on a Sunday afternoon near Aberfeldy. It was in the form of a pony, and it continued grazing as the first girl jumped onto its back. One by one, the other girls followed their friend onto the pony, but only the boy noticed that the pony’s back grew longer to accommodate its riders. Finally, the pony tried to get him on as well. “Get on my back!” it said, and the boy ran, hiding in the safety of the rocks. The terrified girls found that their hands stuck to the each uisge’s back, and they could only scream as it dove into the loch. The next day, seven livers floated to the surface.

The son of the Laird of Kincardine encountered an each-uisge near Loch Pityoulish. He and his friends found a black horse with a bridle, reins, and saddle all made of silver. They got onto it and immediately found themselves on a one-way trip to the loch, their hands glued to the reins. Fortunately for the heir of Kincardine, the youth had only touched the reins with one finger, and freed himself by cutting it off, but he could only watch as the water-horse took his friends with it.

While the water-horse legend may be pervasive and universal in northern Europe, some of the each uisge’s appearances may be more prosaic. The beak and large footprints of some each uisges suggest a leatherback turtle more than they do a horse.

References

Fleming, M. (2002) Not of this World: Creatures of the Supernatural in Scotland. Mercat Press, Edinburgh.

Gordon, S. (1923) Hebridean Memories. Cassell and Company Limited, London.

MacKinlay, J. M. (1893) Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs. William Hodge & Co., Glasgow.

Parsons, E. C. M. (2004) Sea monsters and mermaids in Scottish folklore: Can these tales give us information on the historic occurrence of marine animals in Scotland? Anthrozoös 17 (1), pp. 73-80.