Variations: Égremont, Vif

In Brittany, the Agrippa is one of the most feared and malevolent grimoires, a living book with a mind of its own. Its name in Tréguer is derived from that of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, but it is also known as Égremont in Châteaulin and Vif (“Alive”) around Quimper.

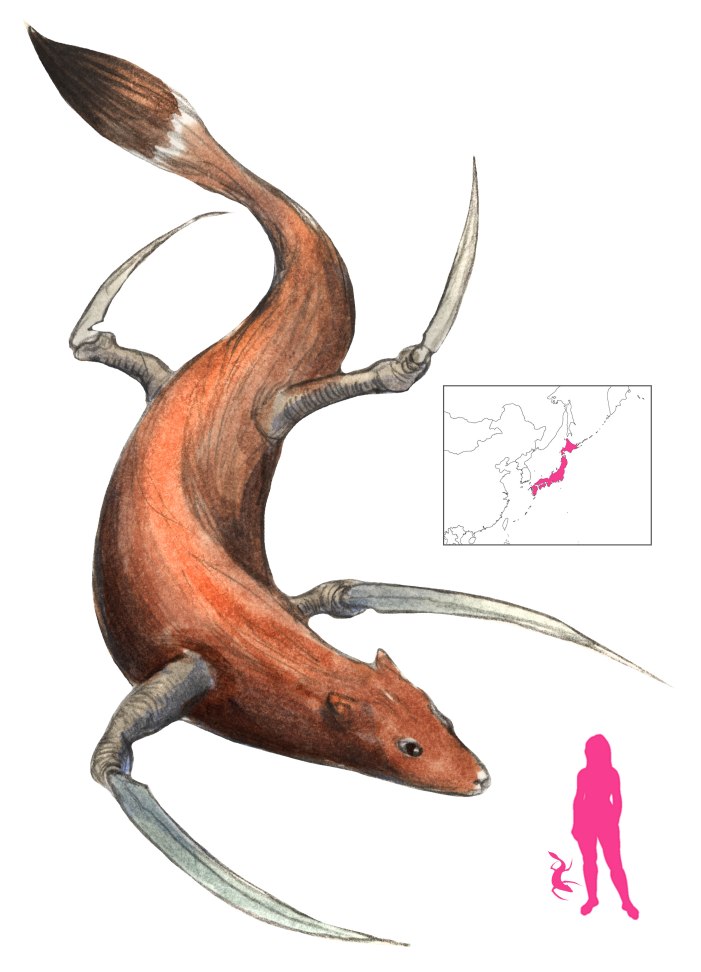

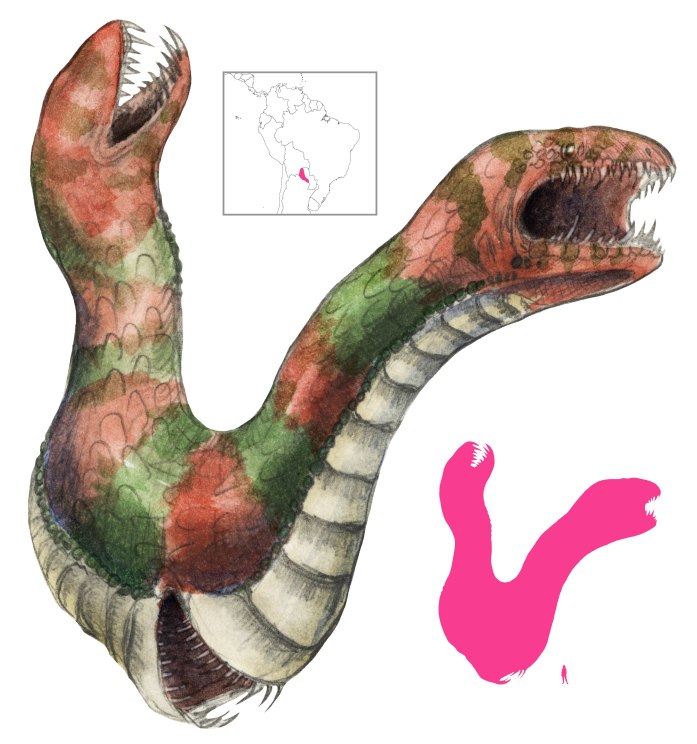

An agrippa is enormous, standing fully as tall as a man. Its pages are red, while its letters are black – although some variants exist with black pages and red text. It contains the names of all the devils, and how to summon them.

Agrippas are living, malicious creatures, and resent being read. An untamed agrippa will display only blank pages. To get the letters to appear, the agrippa must be battled, thrashed, and beaten like a stubborn mule. A fight with an agrippa can last hours, and victors come out of it exhausted and drenched in sweat. When not in use, an agrippa must be chained to a strong, bent beam.

Only priests can be trusted to keep agrippas, as they have the training and the force of will required to master it. They use it to deduce the fate of the dead by calling upon all the demons in order; if none will admit to having taken the deceased’s soul, then they were saved. Long ago all priests had agrippas, and a newly-ordained priest would inexplicably find one on his table. However, agrippas have since found their way into the hands of laymen, and the temptation to use them can be very strong. A priest will not be able to sleep well as long as one of his parishioners has an agrippa.

Uninitiated readers of the agrippa will always smell of sulfur and brimstone, and walk awkwardly to avoid treading on stray souls. A man with an agrippa will find himself incapable of destroying it – a task that will become increasingly desperate, as possession of an agrippa will prevent entry into Paradise. Loizo-goz, a man from Penvénan, tried to rid himself of his agrippa by dragging it away to Plouguiel on the end of a chain, but came back home to find it had returned to its usual place. He then tried burning it, but the flames recoiled from the book. Finally he dumped the agrippa into the sea with rocks tied to it, only to see it climb out of the water, shake its shackles off, and make a beeline for its suspended perch. Its pages were perfectly dry. Loizo-goz resigned himself to his fate.

Eventually a priest will arrive to save the owner of an agrippa. He will wait until the unfortunate is at death’s door, whereupon he will come to his deathbed. “You have a very heavy burden to carry beyond the grave, if you do not destroy it in this world”, he tells him. The agrippa is untied and brought down, and while it tries to escape, the priest exorcises it, and sets fire to it himself. He then collects the ashes, places them in a sachet, and puts them around the dying man’s neck, telling him “May this weigh lightly upon you!”

Other times a priest will have to save a man whose reading of the agrippa took him too far. A Finistère parson found his sacristan missing, and his agrippa open wide on the table. Understanding that the sacristan had summoned the devils and been unable to dismiss them, he started calling upon them one by one until they released him. The sacristan was blackened with soot and his hair was scorched, and he never told a soul of what had transpired.

References

Le Braz, A. (1893) La Légende de la Mort en Basse-Bretagne. Honoré Champion, Paris.

Luzel, F. M. (1881) Légendes Chrétiennes de la Basse-Bretagne, v. II. Maisonneuve et Cie, Paris.

Seignolle, C. (1964) Les Évangiles du Diable. Maisonneuve et Larose, Paris.