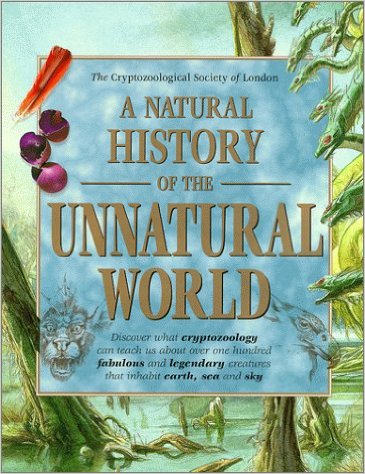

A Natural History of the Unnatural World

by Joel Levy and the Cryptozoological Society of London

The world of teratological books can be a minefield at times. It’s hard to extricate serious research from complete fabrication, and sometimes supposedly serious books (Borges and Dubois’ works notably) have bogus myths that then get parroted by other works as true. Then there are cryptozoological books which generally are separate from myth and folklore… except in this case.

A Natural History of the Unnatural World (ANOTUW from now on) has a special place in my heart for being one of the first books that really got me into mythical entities. Presented as a cryptozoological book written by the ersatz “Cryptozoological Society of London”, it is actually more of a tongue-in-cheek book that treats legendary beasts as cryptids. Oh, and there’s some actual cryptids in there like apemen and the Loch Ness monster, but otherwise ANOTUW is neither fish nor fowl nor alectrocampus. In fact, even the publishers seem to have realized that and reprinted it under the name Fabulous Creatures and other Magical Beings. A much more sensible name, if you ask me, but as I have the original version I will be reviewing that. If you don’t trust my judgement and want to buy it for yourself, you can get it here and here.

Scope

Going by the title you’d think this was a book about cryptozoology, but no self-respecting cryptid manual that I know of has sections on chimeras, simurghs, fairies, basilisks, and griffins. Instead this book covers the wide range of legendary creatures you’d expect from a mythology book. The only actual cryptids are giant invertebrates, lake monsters, the chupacabras, and apemen. Also included are various spotlights on mythical characters who encountered those creatures: Atalanta, Jack the Giant-Killer, Sindbad, and so on. Definitely very broad in scope, which may not be what you’d want as an advanced teratologist. On the other hand, a cryptozoologist would find little in the way of useful knowledge, as the cryptids covered are merely the best-known ones. Besides, lumping them with mythical creatures might be a bit insulting.

Organization

ANOTUW is laid out somewhat haphazardly. The creatures are divided by morphology: Invertebrates, Reptiles, Birds, Mammals, Hybrids, Manimals (that’s human/animal hybrids), and Hominids. The entries themselves are in several different styles: CSL Reviews (magazine entries, the most “serious”-looking ones), Field Reports (field-note style papers and sketches), Letters (correspondence sent to the CSL), assorted document clippings, and large double-page spreads of mythical hero art.

Text

The text makes it clear that the book is not meant to be serious, with plenty of jokes, puns, and stereotypes. The Thunderbird entry is a newspaper clipping from the “Hangman’s Gulch Herald”, complete with an ad for “Dr. Boardman’s Patent Tonic Remedy” and “Pastor’s Dog Has Fleas” in local news. The Phoenix entry is titled “C’mon Baby, Light My Pyre”. The Gremlin entry is especially memorable – I don’t know who started the trend of making gremlin entries seem like they’re falling apart, but I fully condone (and have added to) it. The Black Dog entry is adorable. Other entries offer rational explanations for irrational things – retrovirus origins for lycanthropy, for instance.

It’s all great if the book was a lighter look at mythology, but it’s not billed as such. It would be fine if the book pretended to be mythical creatures explained in a believable way, but it doesn’t claim to be. It’s certainly not a cryptozoological book – at least, I don’t think so. It’s all over the place, and it depends on whether you find it funny or not.

The glossary at the end is a two-page infodump of loads of mythical creatures, many not covered in the book, which makes a good springboard for further reading.

Images

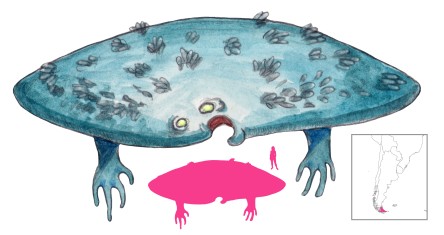

Images are mostly stock photos and archival images, with relatively little original illustration. I do like the sketches sprinkled throughout. The main goal was to try and depict mythical creatures as plausible animals, and ANOTUW largely succeeds. The catoblepas stands out as an image The manticore, chimera, harpy, basilisk, kelpie, chupacabras… all look believable, as though they were field sketches of actual animals. There is all too little of those sketches, which is a shame really.

Various photos of actual animal anatomy are labeled as belonging to mythical creatures. A turtle skull is an amphisbaena’s, shark jaws are a manticore’s… it kind of falls flat if you know your anatomy, but it’s cute none the less.

Research

Pretty good. Almost all the creatures are “actual” mythical creatures, taken and then embellished upon. The book is not meant to be taken seriously and so hasn’t been copied by others repeating the same mistakes. So, for instance, with the kelpie described as a giant salamander, it’s not so much of a problem because it’s easy to tell that that’s interpretation. At least, I think so…

One problem is that the actual information can be hidden under all the extra stuff. Field notes, for instance, could have just one paragraph with legendary information in it, with the rest being accounts of the expedition across two pages.

The other major problem is the reference section. Namely, there is none. Nada. Nil. Zip. Zilch. Not a sausage.

Summary

ANOTUW is a fun, silly book that I have fond memories of, but teratologists will find themselves wanting actual information, while cryptozoologists may well be offended at the treatment of cryptids. I give it 3/5 gigelorums for creativity, design, illustration, and general quantity of creatures, most of which I hadn’t heard of when I first read it. The rating can be raised or dropped one gigelorum, depending on your tolerance for the jokey style.