Variations: Ṣannājah, Ṣunnājah, Sannaja; Nubian Horse (erroneously)

The Ṣannāja, “Cymbalist” (!), is a gigantic, deadly, yet pathetic creature originally described by al-Qazwini. It can be found in the land of Tibet, making it an abominable snowman of sorts, although it has more in common with the Gorgons of Greek myth.

According to al-Qazwini, the ṣannāja is indescribably vast, such that no animal can compare to it in size. This largest of all beasts makes dens one league wide.

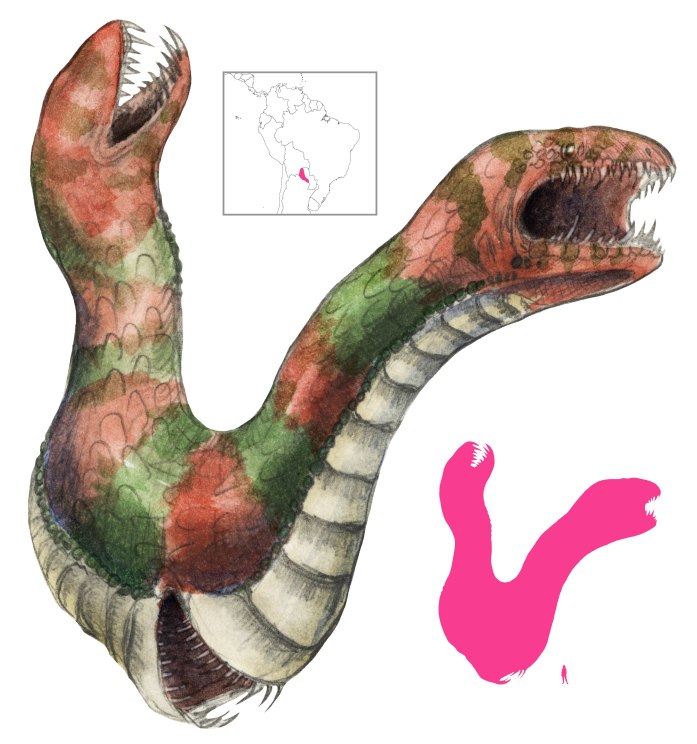

Neither al-Qazwini nor al-Damiri describe its appearance, so artistic depictions of ṣannājas vary. As it is described in the same section along with insects and reptiles, the Wasit manuscript shows it with six stubby legs and a segmented, shelled turtle-like body. Its red, vaguely spiderish head is blank except for hair and two large, staring eyes. The artist of the C.1300 manuscript gives the ṣannāja a tusked, leonine head with massive, spotted folds of skin all over its body. A third is more cautious, assigning it the looks of a dragon. Finally, one Egyptian account is a ṣannāja in name only, placing it in African rivers and giving it four duck feet, a horse’s mane, water-buffalo skin, and a huge mouth. Described as the “Nubian Horse” living in water and ruining crops on land, this is the only case where the name has been applied to the hippopotamus.

The most distinctive quality of the ṣannāja is its deadly gaze, which nonetheless has a peculiar quality. Any animal that sees the ṣannāja dies instantly, but if the ṣannāja sees the animal first, it is the one to expire. Thus animals of Tibet come up to ṣannājas with their eyes closed, such that the monster will see them and drop dead, guaranteeing them a feast for weeks to come.

Accounts of mammoth fossils from Central Asia may have inspired the enormous ṣannāja. Traditional Tibetan art and kirttimukha faces may also have had a hand in its genesis.

References

Berlekamp, P. (2011) Wonder, Image, and Cosmos in Medieval Islam. Yale University Press, New Haven.

al-Damiri, K. (1891) Hayat al-hayawan al-kubra. Al-Matba’ah al-Khayriyah, Cairo.

Jayakar, A. S. G. (1908) Ad-Damiri’s Hayat al-Hayawan (A Zoological Lexicon), vol. II, part I. Luzac and Co., London.

Komaroff, L. and Carboni, S. (eds.) (2002) The Legacy of Genghis Khan. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Rapoport, Y. and Savage-Smith, E. (eds.) (2014) An Eleventh-Century Egyptian Guide to the Universe. Brill, Leiden.

al-Qazwini, Z. (1849) Zakariya ben Muhammed ben Mahmud el-Cazwini’s Kosmographie. Erster Theil: Die Wunder der Schöpfung. Ed. F. Wüstenfeld. Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, Göttingen.