Variations: Vaivre, Givre, Guivre, Wivre

Vouivres, the great fiery serpents of France, have been reported primarily from remote, mountainous regions, where they haunt springs, wells, caves, deep ponds, and ruined castles. They are known from Bourgogne, Franche-Comté, Savoie, the Jura mountains, and neighboring areas, with possible relatives in the Aosta Valley and Switzerland.

The word “vouivre” is derived from the Latin vipera, or “viper”. Vouivres themselves are the spiritual descendants of Mélusine, stripped of her human features. They have been described as dragons, serpents, and fairies in the form of great reptiles; they are always the guardians of priceless treasures.

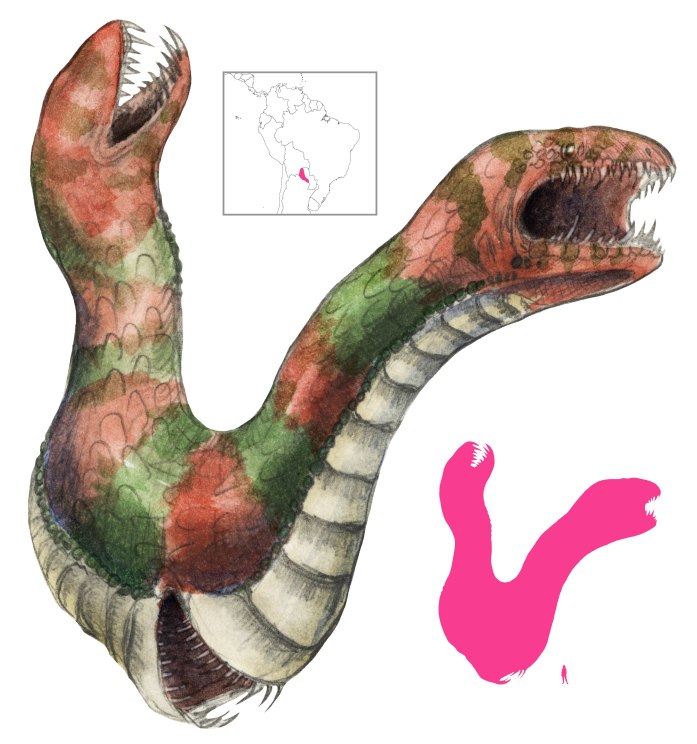

In its most simple definition, a Vouivre is a female dragon. Vouivres vary wildly in appearance, but are always female and associated with fire and water. The classic vouivre, as observed in Faverges, Fleury-la-Tour, Mont-Beuvray, Rosemont, Solutré, and Thouleurs, is an immense winged serpent covered with fire. Instead of eyes, a vouivre has a single large diamond or ruby in its head that guides it through the air. She removes it when bathing, leaving it blind and vulnerable to theft. Possession of a vouivre’s eye-stone would bring riches and happiness to anyone who stole it. The immense vouivre of Boëge guards treasure and wears a priceless golden necklace. In La Baume she is 4 meters long and covered in gems and pearls. She sometimes leaves gems behind where she lands. The Lucinges vouivre is a glowing red viper that whistles eerily in flight. The Gemeaux vouivre, which appeared between 2 and 3 in the afternoon, was hooded like a cobra.

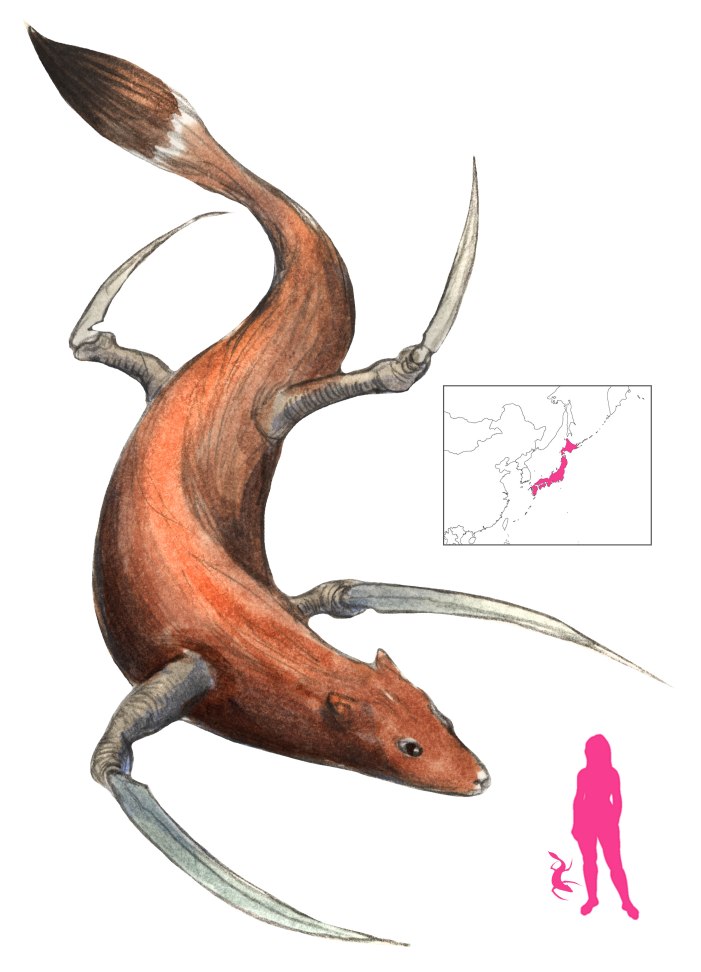

In Brizon, she is equally likely to appear as a bird or a winged beech marten with a brilliant necklace as she is to have the form of a great serpent with wings and a diamond on its tail. Vouivres may not even look like animals. In Chevenoz she appears as a burning fireball streaking across the sky, in Saint-Jean-d’Aulps and Vallorcine she is a single-eyed tongue of fire, and in Le Biot she is a star whose appearance foretells war and strife. The Orgelet Castle vouivre looks like a red-hot iron bar in flight, and the vouivre of Sixt-Fer-À-Cheval is a plumed golden necklace that flies through the air.

One of the more effective ways of slaying a vouivre has been making a spiked barrel to hide in. At Condes, a man managed to steal a vouivre’s diamond and hide in a nail-studded washtub; the infuriated, blinded dragon killed herself trying to get to him. While another man at the Aosta Valley slew a vouivre in a similar manner, other prospective thieves have not been so lucky. The vouivre of Reyvroz had a necklace of great value, which was stolen by a man in a spiked barrel; she died and the thief died soon after. The vouivre of Samoëns had her pearl necklace stolen in the same manner, but she constricted the barrel anyway and made the thief return the necklace; she then disappeared and was never seen again. In Manigod, where grass would not grow for a couple of years after the vouivre’s passage, a man who stole her diamond was killed, his barrel smashed, and the gem retrieved.

Finally, as with all dragons, vouivres are vulnerable to the power of saints and other holy persons. The vouivre of Saint-Suliac was cast into a deep cave by Saint Suliac after she killed one of his monks. The location became known as the Trou de la Guivre, the Guivre’s Hole.

In Thollon-Les-Mémises, among other places, “vouivre” has become a byword for an unpleasant, nasty woman.

Modern versions of the vouivre, perhaps conflating her with Mélusine, have embellished with her the features of a seductive woman. Marcel Aymé makes her a wild girl of the forest with an entourage of vipers, and Dubois makes her a beautiful fairy who sheds her dragon skin when bathing.

References

Aymé, M. (1943) La Vouivre. Gallimard.

Dontenville, H. (1966) La France Mythologique. Tchou, Paris.

Dubois, P.; Sabatier, C.; and Sabatier, R. (1996) La Grande Encyclopédie des Fées. Hoëbeke, Paris.

Joisten, C. (2010) Êtres fantastiques de Savoie. Musée Dauphinois, Grenoble.

Monnier, D. (1819) Essai sur L’Origine de la Séquanie. Gauthier, Lons-Le-Saunier.

Sébillot, P. (1905) Le Folk-Lore de France, Tome Deuxième: La Mer et les Eaux Douces. Librairie Orientale et Américaine, Paris.