Variations: Baconaua (Hiligaynon)

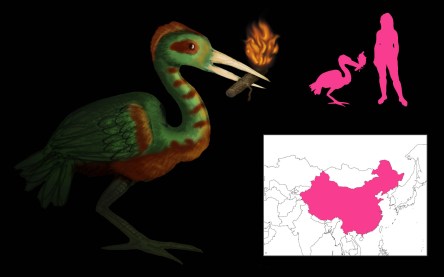

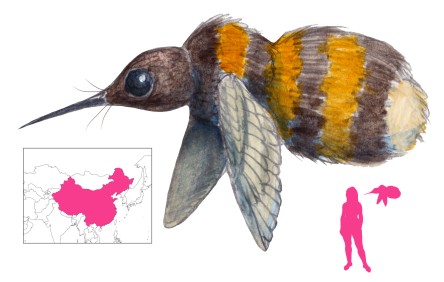

The Asian eclipse monster has analogues in China, India, Malaysia, Mongolia, Thailand, and the South Sea Islands. In the Philippines, where the legend is widespread, it is usually a dragon or serpent or even an enormous bird. Bakunawa, “Eclipse”, is one of the best-known.

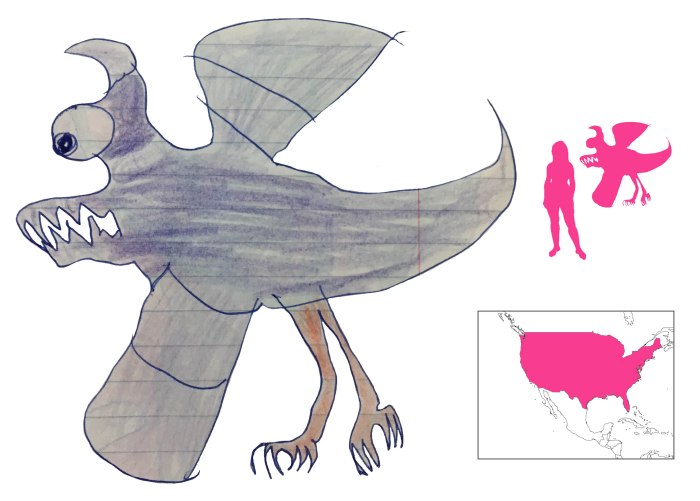

The Bakunawa of the Cebuano, or Baconaua as it is known to the Hiligaynon, is a colossal, fishlike dragon as large as the Negros and Cebu islands. It resembles a shark, with gills, a lake-sized mouth, and a striking red tongue. Whiskers one palmo long adorn its mouth. In addition to its powerful ash-gray wings, it has smaller wings along its sides.

Long ago there were seven moons in the sky. Bakunawa gobbled them up one by one until it came to the last and largest moon. It failed to swallow it, and tried to bite it into manageable chunks, sinking its teeth deep into the moon’s surface. To this day the bakunawa’s teeth-marks can still be seen on the moon. Every now and then the bakunawa will take to the sky and attempt to finish the job it started by swallowing the moon, causing an eclipse. To make it release the moon, utensils are clanged loudly together to startle it.

The bakunawa’s den is in the deepest parts of the sea. In January, February, and March its head faces north and its tail south; in April, May, and June its head faces west and its tail east, in July, August, and September its head points south and its tail north; and in October, November, and December its head is east and its tail west. The positions of the bakunawa during those four phases are used to divine the best time to build houses.

A children’s game called Bakunawa for 10 or more players involves one player as Buan, the moon, while another is Bakunawa. The remainder form a circle, holding hands and facing inwards. The moon starts inside the circle and Bakunawa is outside. The goal of the children in the circle is to prevent Bakunawa from entering the circle and capturing the moon – the moon itself cannot leave the circle. Bakunawa can ask individual players “What chain is this?” and they can answer that it is an iron, copper, abaca, or any material they can think of. When Bakunawa captures the moon, the players exchange roles or swap with players in the circle.

References

Jocano, F. L. (1969) The Traditional World of Malitbog. Bookman Printing House, Quezon City.

de Lisboa, M. (1865) Vocabulario de la Lengua Bicol. Establecimento Tipografico del Colegio de Santo Tomas, Manila.

Ramos, M. D. (1971) Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. University of the Philippines Press, Quezon.

Ramos, M. D. (1973) Filipino Cultural Patterns and Values. Island Publishers, Quezon City.

Ramos, M. D. (1990) Tales of Long Ago in the Philippines. Phoenix Publishing House, Quezon City.

Reyes-Tolentino, F. and Ramos, P. (1935) Philippine Folk Dances and Games. Silver, Burdett and Company, New York.