Not Appearing in ABC: The Ozaena

The Ozaena is one of those creatures that has gained some traction due to the excellent Bestiary by Jonathan Hunt. I won’t reproduce the image in question, but it can probably be found easily enough. Be careful though as “ozaena” is also a medical condition, and the images are unpleasant.

In it, the entry for O describes the Ozaena or “stink-polyp” as a hideous, be-tentacled blue creature with a foul smell. Hunt makes it look more alien, or something like a sea anemone – a polyp, presumably.. It varies in size from tiny to enormous, with one Spanish terror growing to the size of a ninety-gallon cask.

Quite a memorable creature, eh? Shame it doesn’t exist.

To understand what we’re talking about, we need to specify what polyp means. It’s not polyp as we understand it today, but short for polypus or “many-legs”. It is no more or less than the ancient term for the octopus.

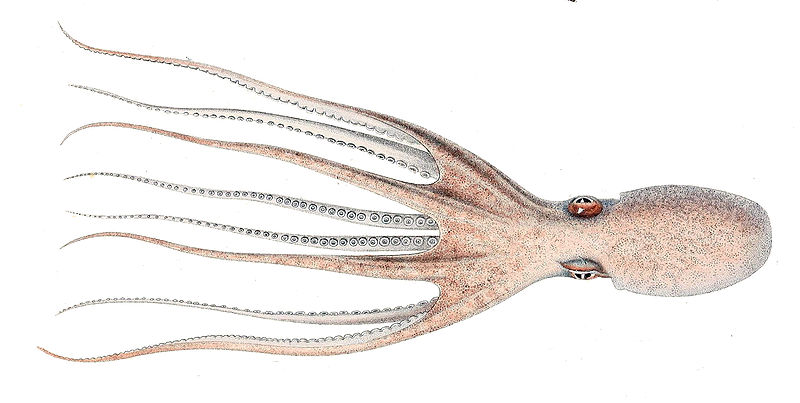

Aristotle distinguishes several kinds of octopus. Amongst those are the eledone, the bolitaena, and the ozolis – what would eventually become the Roman ozaena. Those are small in size and variegated, and have only one set of suckers along their tentacles. In other words, our ozaena is none other than the musky octopus Eledone moschata, which smells of musk. One of its synonyms is Ozoena moschata. It is neither huge nor terrifying.

The giant octopus story is in fact a separate account, unrelated to the ozolis, ozaena, or whatever. An enormous octopus came ashore at Dicaerchia in Italy, where it ravaged the cargo of Iberian merchants. The merchants would leave pickled fish in large jars on the shore, and the octopus would haul itself out of the water, break the jars, and eat the fish. This happened multiple times, and the merchants could not understand who the thief could be. A servant was left on guard one moonlit night, and he reported the incredible occurrence to his masters. The next time the octopus appeared it was assaulted with axes and slain.

So there you have it, a Frankensteined account creating an alien creature from our modern unfamiliarity with archaic terms and our tendency to lump accounts together for convenience.

It’s alright. Shake off the heartbreak, there’s plenty more creatures to make up for it. With that I leave you with Thomas de Cantimpré’s imagery of the octopus or polypus, apparently in the process of drowning someone.