Variations: Lucooma

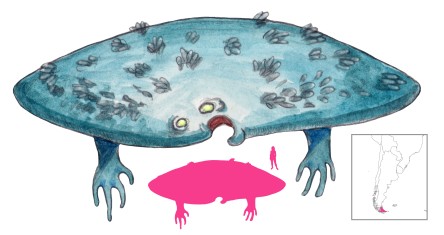

According to the Yamana, the Lakúma are the most dangerous sea creatures of Tierra del Fuego. These water spirits have been known to tip canoes over, pull their occupants out, and drag them under to consume, leaving their entrails to float to the surface. They can also create huge waves, summon whirlpools, and whip up storms to damage larger vessels.

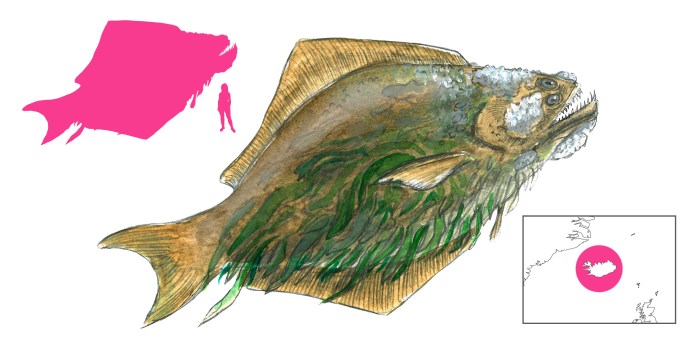

Lakúma have been compared to whales, squids, and giant worms, making their exact appearance hard to pin down. What is known is that they like to flatten themselves out on the water’s surface, letting their back protrude like a small island. Their broad and flat backs are covered with encrustations of unusually large mussels.

Sometimes there are so many lakúma in one spot that they can be used as stepping-stones. A group of Yamana on a desert island saw countless wide, flat lakúma rise to the surface, forming a living bridge to a bountiful island. “If we run quickly, we’ll get to the other side!” said one man, running over the backs of the lakúma and reaching the other shore. But the others were too slow, and the lakúma dove, taking them to a watery grave. The one survivor recruited enough men to slay many lakúma in retaliation, and their bodies can still be seen today in the form of large, flat stones at the bottom of the sea.

Lakúma will also attack people breaking taboos. It is known that a menstruating girl or túrikipa should not eat berries, but one girl thought she could circumvent the rule by sucking out the juices and spitting the solid outer part. Alas, her canoe was attacked by a lakúma, and it refused the offerings tossed at it until it took the girl and devoured her. It then flattened itself out on the surface and rested. The túrikipa’s people went onto the lakúma’s back, took some of the mussels, and used their sharp shells to dismember the lakúma. But that was small comfort for the túrikipa, whose entrails served as a grisly reminder of her fate.

For all their malevolence, lakúma can be tamed by a powerful yékamuš or shaman, and can become obedient servants. One yékamuš was with his wife in their canoe while she scolded him. “I thought you were a powerful yékamuš, but you can’t even strand a whale, or fetch birds to eat!” In response the yékamuš slept and summoned two lakúma, who raised the canoe’s bow up in the air. “Wake up! Help me!” cried his wife, and the yékamuš stirred and spoke nonchalantly. “I thought you said I was powerless”, he taunted, before telling her to paint the lakúma with white paint. She did as she was told, and the lakúma did not resist. Then they dove and created a good breeze to send the canoe effortlessly to its destination. “I had always made fun of you”, admitted the wife, “but now I know you are truly a capable yékamuš!”

References

Gusinde, M.; Schütze, F. trans. (1961) The Yamana; the life and thought of the water nomads of Cape Horn. Human Relations Area Files, New Haven.

Gusinde, M.; Wilbert, J. ed. (1977) Folk Literature of the Yamana Indians. University of California Press, University of California, Los Angeles.