Variations: Shor Ha-bar (“Wild Ox”), Bahamut, Bahamoot

Behemoth is the plural form of the Hebrew behemah, or “animal”; appropriately, the word is used to describe a creature of vast size and bulk.

The best-known reference to Behemoth is offered in the Biblical book of Job (40:15-24), where it is mentioned in God’s whirlwind tour of humbling natural wonders. The Behemoth eats grass like an ox, and its strength is in its muscular loins and tight-knit thigh sinews. Its tail stiffens like a cedar, its bones are like bronze, and its legs like iron bars. Despite its power, it is apparently passive and indolent, lying in marshes under lotus plants, and feeding in the mountains alongside the wild animals. Behemoth does not fear the river when it rushes into its mouth, and cannot be taken with hooks; only God can approach it.

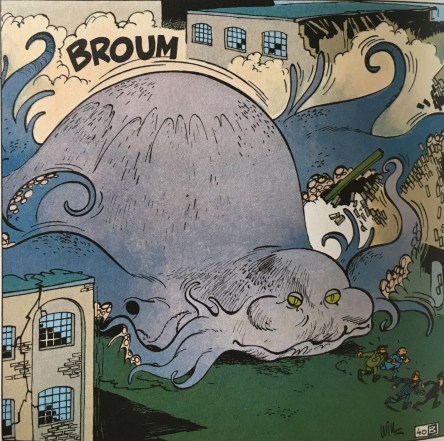

Psalms 50:10 makes reference to “the behemoth on a thousand hills”, nowadays translated to “the cattle on a thousand hills”. The Midrash elaborates on that, making the Behemoth large enough to sit on the thousand mountains it feeds on, and making it drink six to twelve months’ worth of the Jordan River in one gulp.

The Talmud gives the Behemoth further cosmic significance. The behemoth were created male and female, but to prevent them destroying the Earth, God castrated the male and preserved the female in the World-to-Come for the righteous. This vision of the Behemoth has been interpreted as metaphoric, with the Behemoth representing materialism and the physical world.

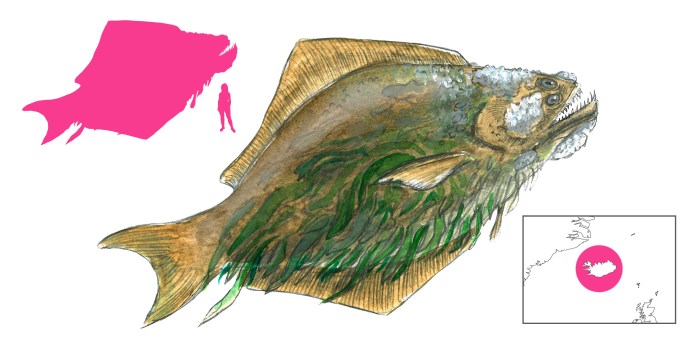

If Behemoth is an animal known to us today, the primary candidates are the wild ox, the elephant, and the hippopotamus. The wild ox seems dubious, otherwise the Behemoth would not eat grass “like” an ox. The elephant’s trunk may have been the basis for the “tail”, but the description refers to stiffening, something which the hippo’s tail does. Another possibility is that the “tail” is in a fact a euphemism, and the description refers to the virility and vigor of the bull hippopotamus. Further details – living in water, feeding on land, a mouth big enough for the Jordan to rush into, terrifying power – all but prove that the hippopotamus is the subject of Job’s verses. Bochart agreed, heading his discussion of Behemoth with “non esse elephantum, ut volunt, sed hippopotamum“.

The Arabian Bahamut is a further magnification of the already-large Behemoth, turning it into a vast cosmic fish, one of the foundations on which the Earth stands. It is so big that all the seas and oceans of the Earth placed in its nostril would be like a mustard seed in a desert.

Behemoth is now a synonym for any large animal. Buel gives us behemoth as a possible originator of the word “mammoth”, alongside the Latin mamma and the Arabic mehemot.

The suggestion that Behemoth is a late-surviving dinosaur is best left unaddressed.

References

Bochart, S. (1675) Hierozoicon. Johannis Davidis Zunneri, Frankfurt.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Buel, J. W. (1887) Sea and Land. Historical Publishing Company, Philadelphia.

Coogan, M. D.; Brettler, M. Z.; Newsom, C.; Perkins, P. (eds.) (2010) The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Slifkin, N. (2011) Sacred Monsters. Zoo Torah, Jerusalem.