Variations: Lamiae (pl.); Empusa, Empousa, Empuse, Empusae (pl.); Mormo, Mormolykiae (pl.); Gello, Gelloudes (pl.); Lilith

Demons

Binaye Ahani

Variations: Bina’ye Ayani, Nayie A’anyie, Bina’yeagha’ni, Eye Killers, Evil Eyes

The Binaye Ahani, or “Eye Killers”, were among the many Anaye that were slain by Nayenezgani. As with the other original Anaye or “Alien Gods”, they were born from human women who had resorted to unnatural practices. Their “father” was a sour cactus.

The Binaye Ahani were twins born at Tse’ahalizi’ni, or “Rock With Black Hole”. They were round with a tapering end, no limbs, and depressions that looked like eyes. Their horrified mother abandoned them on the spot, but they survived to grow into monsters; as they were limbless, they remained where they were born. Instead of hunting prey actively, they could fire lightning from their eye sockets and fry anyone who approached them. In time eyes developed in the depressions on their head, and they could kill with their eyes as long as they kept them open. Magpie was their spy, and they had many children who took after them in the worst way.

Nayenezgani prepared for his fight with the Binaye Ahani by taking a bag of salt with him, and found the old twins in a hogan with their offspring. The monsters immediately stared at him, lightning shooting from their bulging eyes, but Nayenezgani’s armor deflected the beams. He responded by throwing salt into the fire, which spluttered and sparked into their eyes, blinding them. With the Binaye Ahani in disarray, Nayenezgani waded in and killed all but the two youngest. He took the eyes of the first Binaye Ahani as trophies.

“If you grew up here, you would only become things of evil”, he told the survivors, “but I shall make you useful to my people in years to come”. To the older one, he said “You will warn men of future events, and tell them of imminent danger”, and it became a screech owl. To the younger he said “You will make things beautiful, and the earth happy”, and it became a whippoorwill.

In other versions the surviving children become a screech owl and an elf owl, while the parents are turned into cacti.

References

Locke, R. F. (1990) Sweet Salt: Navajo folktales and mythology. Roundtable Publishing Company, Santa Monica.

Matthews, W. (1897) Navaho legends. Houghton Mifflin and Company, New York.

O’Bryan, A. (1956) The Diné: Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians. Bulletin 163 of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Reichard, G. A. (1950) Navaho Religion: A Study of Symbolism. Bollingen Foundation Inc., New York.

Bosch

Sometimes criminals face supernatural retribution for their crimes. In the Finistère region of Brittany, it is the victim that suffers instead. Crimes committed on board develop a life of their own and linger long after the guilty party has left the ship. Acts of greed summon evil spirits that populate the ship, bringing bad luck to the crew. In such cases humid straw must be burned to fumigate the ship. The demons can become small enough to hide in a thimble, so the smoke must reach every part of the ship. This must be performed before heading out to sea to avoid potential disaster.

In Audierne, committing a maritime theft actually guarantees good luck. The creature left behind is a Bosch, the physical manifestation of onboard theft. They have no clear appearance, and probably vary depending on the nature of the crime they embody. These wretched creatures come into existence after a theft occurs on a ship, and have a lifespan of a few months to a few years, at the end of which they weaken and disappear. During this time they hide in the bow of the ship and make life on board absolutely miserable. As long as a bosch is present, the nets will be empty, the wind will not blow, and bad luck will hound the crew.

Simply waiting for a bosch to die is therefore impractical. If a ship finds itself afflicted with a bosch, there are two ways to get rid of it. One is to steal an object from a “happy” ship, one whose crew is satisfied and whose catches are always plentiful. The ship should be moored near it, and during the following night the captain sneaks on board the other ship to steal some small object, usually a pair of oarlocks. The bosch will then go to other ship and become their problem.

If one does not wish to inflict the misery of a bosch on an innocent ship, the demon can be exorcised instead. The captain must steal a quantity of hay and hide it in the boat. At night he should set fire to the hay near the mizzenmast and yell “Devil on board!” The sailors, startled, will grab anything within reach and lash out randomly, beating every corner of the ship. Surrounded and beaten, faced with choking smoke and scorching flames, the terrified bosch dives into the sea.

References

van Hageland, A. (1973) La Mer Magique. Marabout, Paris.

Davalpa

Variations: Devalpa, Dawal-bay, Himantopus, Himantopode, Sciratae, Shaikh al-Bahr, Old Man of the Sea, Tasma-pair, Nasnas (erroneously)

“Would you be so kind as to carry me across the river?” The Davalpa, or “strap-leg”, looks up at you as he begs in a wheedling voice. It’s hard to deny the old man this one favor. He’s hunched, frail, and withered, dressed in rags which cover his entire body. It can’t hurt to help him, and you easily lift him up onto your shoulders. It is then that his legs appear – long, leathery straps that burst out of his clothes and wrap themselves around your neck. You find yourself barely able to breathe, staggering under your charge’s weight, all while the davalpa cackles and whips you, ordering you to move where he wishes. You’re his prisoner now, and will remain so until your death.

That is how davalpas catch their victims. Their legs, while 3 meters long and powerful, do not let them move around normally, and so they use unwilling humans as their mounts. Sometimes they have multiple long snakelike legs that erupt out of their belly, and a tail they use to whip their mounts. Sometimes they constrict their victims to death, a merciful fate compared to the slavery they impose.

Davalpas can be found in the Iranian deserts and on uncharted islands in the Indian Ocean, where they sit by the side of the road and wait for potential rides to show up. The most famous davalpa was the Old Man of the Sea, which Sindbad the Sailor met on his fifth voyage. The Old Man successfully enslaved Sindbad, forcing him to do his bidding, but Sindbad managed to escape the creature’s clutches by fermenting grape juice and offering it to him. After getting drunk, the Old Man’s grip loosened and he fell off; Sindbad smashed his head with a rock.

Sindbad’s adventure with the Old Man of the Sea is almost an exact copy of previous accounts. Al-Qazwini locates the davalpas on Saksar Island, which they share with the cynocephali. A sailor tells the story of how a strange person wrapped his legs around his neck and enslaved him, forcing him to pick fruits. He escaped by fermenting grapes and inebriating the davalpa; the experience left him with scars on his face.

Al-Jahiz refers to the creature as dawal-bay in Arabic. As with the Waq-waq, he believes it to be a cross between plants and animals.

Oddly enough, the davalpa is not of Persian origin. The earliest mention of davalpas is from Alexander’s Romance, where they are called the “savage Himantopodes” and share their land with Cynocephali, Blemmyes, Troglodytes, and other strange races. Himantopus means “strap foot”, and is currently in use today for the black-winged stilt, a shorebird with long slender legs. Pliny specifies that those strap-foots are incapable of walking, and get around by crawling; later he describes the snub-nosed, bandy-legged Sciratae, which seem to be one and the same.

One possibility is that the davalpa was inspired by apes, which can cling tightly and whose shorter legs might be less apparent at first glance. More intriguingly, Tornesello suggests that the various monstrous races of Hellenic myth arose from recollections of foreign soldiers during the Greco-Persian wars. The Sagartians in Xerxes’ army rode horses and used twisted leather lariats to entangle and kill enemies. The parallels with them and the davalpas include the leather-strap weapon, its use in strangling people, and the apparent incapability of walking (the Sagartians were always on horseback). Sagartioi can also be seen as the linguistic ancestor of Skiratoi.

Thus the davalpa concluded its journey. Inspired by Greek distortions of Persian warriors, it found its way back to Persia where it had lost all of its previous subtext and gained entirely new meaning. Today modern Iranian satirists and cartoonists have used the davalpa to represent greedy, parasitic institutions – especially helpful if those institutions disapprove of direct criticism.

References

Browne, E. G. (1893) A Year Amongst the Persians. Adam and Charles Black, London.

Christensen, A. (1941) Essai sur la Démonologie Iranienne. Ejnar Munksgaard, Copenhagen.

del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; & de Juana, E. (eds.) (2013) Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Al-Jahiz, A. (1966) Kitab al-Hayawan. Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi wa Awladihi, Egypt.

Marashi, M. (1994) Persian Studies in North America. Iranbooks, Bethesda.

Masse, H. (1954) Persian Beliefs and Customs. Behavior Science Translations, Human Relations Area Files, New Haven.

Al-Qazwini, Z. (1849) Zakariya ben Muhammed ben Mahmud el-Cazwini’s Kosmographie. Erster Theil: Die Wunder der Schöpfung. Ed. F. Wüstenfeld. Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, Göttingen.

Ricks, T. M. (1984) Critical Perspectives on Modern Persian Literature. Three Continents Press, Washington D. C.

Tornesello, N. L. (2002) From Reality to Legend: Historical Sources of Hellenistic and Islamic Teratology. Studia Iranica 31, p. 163-192.

Lange Wapper

Variations: Lange-wapper, Long Wapper

Centuries ago, the woods around Antwerp crawled with demons, goblins, and all sorts of evil creatures. They became so troublesome that the townsfolk organized a massive raid, mobilizing priests and arming themselves with bell, book, candle, and icons of the Virgin Mary. The countryside was scoured, and every monster they found was exorcised and banished to the sea.

They did not check the water. One creature escaped their attention by waiting quietly for them to leave. From there he made his way into the canals of Antwerp, where he settled down and incubated his resentment towards humanity.

This was Lange Wapper, or “Long Wapper”. As a shapeshifter, he has no fixed appearance or size. He can be be taller than buildings or the size of a mouse. However, his favored forms usually have long, skinny legs with which he walks on water. These legs can stretch to enormous lengths, allowing him to peer in windows and terrify the inhabitants. The strange movements he makes on those stilt-like legs are the origin of his name, as wapper is an antiquated term for “balance”, and an even more ancient term for “big man”.

Lange Wapper revels in his shapeshifting powers, using them for pranks of varying cruelty. He can become an abandoned kitten, a scared-looking dog, a priest, a nun, a rich man, a beautiful woman, a beggar in rags… any shape that lets him draw unsuspecting victims towards him. Other times Lange Wapper grows to gigantic size and towers over drunkards staggering home at night, frightening them to death. He can duplicate himself as much as he likes, filling dark alleyways with monstrous apparitions. Wappersrui and Wappersbrug are some of his preferred haunts.

A form he often used was a newborn baby, crying on the side of the road. If someone picked him up out of pity, they found their burden slowly growing in weight, until they finally drop it in alarm. The demon then laughs hysterically, and dives back into the canal. He loves milk and especially likes playing this trick on mothers and wet-nurses, draining them dry before making his escape. Lange Wapper also does his best to delay midwives and doctors from attending to women in childbirth.

One time Lange Wapper turned himself into a woman who had four suitors, and soon enough the first suitor arrived to demand her hand in marriage. “I accept, but only if you go to the Notre-Dame cemetery and lay yourself across the crucifix, until midnight”. Confused but elated, the man set off. He was followed by the second suitor, who made the same proposal. “Of course! But only if you go to the Notre-Dame cemetery, take a coffin, carry it to the crucifix, and lie in it until midnight”. The third suitor was told to knock three times on the lid of the coffin, and the fourth had to take an iron chain and run around the crucifix three times, dragging the chain behind him. As expected, the first suitor died of fright when he saw the second crawl into the coffin, the second had a heart attack when the third knocked on his coffin, and the third dropped dead when he heard the fourth running around and rattling his chain. The fourth suitor, baffled, returned to his lover – the real one, this time – to tell her the news, and she committed suicide upon hearing it. Lange Wapper found all this quite amusing.

Lange Wapper does have a soft spot for children, and often becomes a child himself to play with them. But old habits die hard, and he still can’t resist ending the games with some prank.

Unfortunately for Lange Wapper, Antwerp became more and more hostile to him. Modernization of the canals was certainly an annoyance, but the worst came when his fear of Our Lady was discovered. Images of the Virgin Mary proliferated, and soon the demon found himself facing religious imagery everywhere. He has not been seen in a long while; for all we know, he has given up and returned to the sea.

References

Griffis, W. E. (1919) Belgian Fairy Tales. Thomas Y. Crowell, New York.

van Hageland, A. (1973) La Mer Magique. Marabout, Paris.

Teirlinck, I. (1895) Le Folklore Flamand. Charles Rozez, Brussels.

Teelget

Variations: Teel get, Teelgeth, Delgeth

As one of the Anaye, the “Alien Gods” of Navajo folklore, Teelget was born from a human woman who resorted to unnatural and evil practices. In this case, his “father” was an antler. The creature born was round, hairy, and headless, and was cast away in horror; it was this creature that grew into the monster known as Teelget.

The origin of Teelget’s name is not known with certainty, but the “tê” makes reference to his horns. He is like an enormous, headless elk or antelope, rounded in shape, hairy like a gopher, with antlers he uses as deadly weapons. Coyote was his spy, and between him and the other Anaye they laid waste to the land, slaughtering many.

It was Nayenezgani, “Slayer of Alien Gods”, who finally put an end to Teelget’s reign of terror. Armed with his lightning arrows, the hero tracked Teelget down, finding the monster resting in the middle of a wide open plain.

How was Nayenezgani to sneak up on Teelget without being noticed? The grass offered no cover, and Teelget was sure to detect him and retaliate. As he considered his options, he was greeted by Gopher. “Why are you here?” said Gopher. “Nobody comes here, for all are afraid of Teelget”. When Nayenezgani explained that he was here to destroy Teelget, Gopher was more than happy to help. He said that he could provide a way to reach Teelget, and all he asked for as payment was the monster’s hide.

Gopher then excavated a tunnel that led right under the sleeping Teelget’s heart, and dug four tunnels – north, south, east, and west – for Nayenezgani to hide in after Teelget woke up. He even gnawed off the hair near Teelget’s heart, under the pretext that he needed it to line his nest.

That was all Nayenezgani needed. He crawled to the end of the tunnel and fired a chain-lightning arrow into Teelget’s heart, then ducked into the east tunnel. Enraged and in agony, Teelget gouged the east tunnel open with his antlers, only to find that Nayenezgani had moved to the south tunnel. He destroyed that, then the west tunnel, but he only managed to put an antler into the north tunnel before succumbing to his injury.

Nayenezgani couldn’t tell if Teelget had died or not, so Ground Squirrel volunteered to inspect. “Teelget never pays attention to me”, he explained. “If he is dead, I will dance and sing on his antlers”. Sure enough, Ground Squirrel celebrated on top of the fallen monster, and painted his face with Teelget’s blood; ground squirrels still have streaks on their face after that day. In some retellings Chipmunk fills this role, painting stripes down his back.

A chunk of antler and a piece of liver were taken by Nayenezgani as trophies, but Gopher went to work at once skinning Teelget. “I will wear his skin, so that when humans increase once more, they will be reminded of Teelget’s appearance”. And to this day, rounded, hairy gophers still wear the skin that Teelget once wore.

References

Alexander, H. B. (1916) The Mythology of All Races v. X: North American. Marshall Jones Company, Boston.

Locke, R. F. (1990) Sweet Salt: Navajo folktales and mythology. Roundtable Publishing Company, Santa Monica.

Matthews, W. (1897) Navaho legends. Houghton Mifflin and Company, New York.

O’Bryan, A. (1956) The Diné: Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians. Bulletin 163 of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Davy Jones

Variations: David Jones

Where there is the sea, there will be Davy Jones. He is the demon of the ocean, the proprietor of Davy Jones’ Locker where all drowned sailors go. Originally from British tales, he has since been expanding his influence across the ocean; as long as sailors fear the deep, this “blackguard hell’s baby” will continue to exist.

There is no limit to the shapes Davy Jones can appear in. He is the whale, the shark, the whirlpool, the giant squid, the hurricane, all the fears of sailors. He has been described with huge saucer eyes, triple rows of teeth, a tail, and horns, with blue smoke pouring from his nostrils. When the sailors of the Cachalot landed an enormous, barnacle-crusted bull sperm whale with a twisted lower jaw, some of them declared they had killed Davy Jones himself.

Davy Jones rules over the lesser demons and spirits of the sea, and they do his bidding. He can be seen in various forms on the rigging of doomed ships, gleefully announcing their impending destruction. All who die at sea and sink to the bottom of the ocean – Davy Jones’ Locker – are his.

The first literary appearance of Davy Jones was in Defoe’s Four Years Voyages, as a passing remark. The origin of the name is unknown. One unlikely possibility is a corruption of Duffy Jonah, the ghost (Duppy) of the Biblical Jonah associated with storms at sea. Another possibility is that he was based on a real person. There was a sailor, mutineer, and eventual pirate by the name of David Jones in the early 1600s, and the Locker may have been expression he was fond of. Unfortunately there is no fully convincing explanation for the origin and etymology of Davy Jones.

References

Bullen, F. T. (1906) The Cruise of the Cachalot. MacMillan and Co., London.

Defoe, D. (1726) The Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts. A. Bettesworth, London.

Smith, A. The Perils of the Sea: Fish, Flesh, and Fiend. In Davidson, H. E. and Chaudhri, A. (2001) Supernatural Enemies. Carolina Academic Press, Durham.

Smollett, T. (1882) The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle. George Routledge and Sons, London.

Puaka

Variations: Puwaka, Puaki

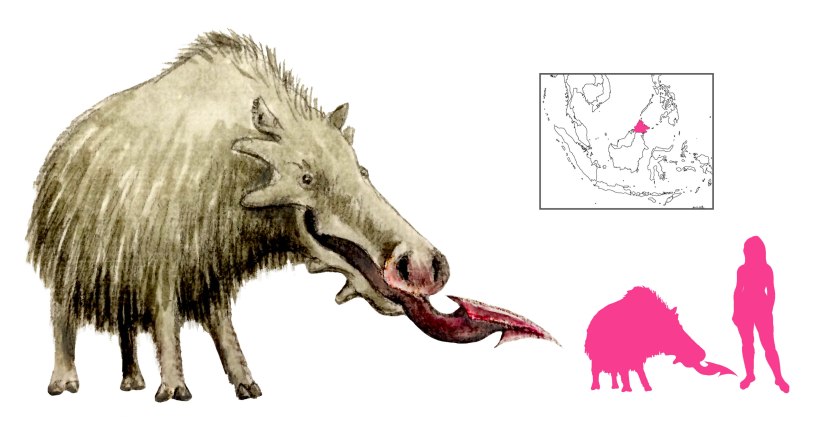

The Puaka (“Pig”) is a Dusun demon that guards water in eddies, and resembles a pig with a razor-sharp tongue. Puakas like to feed from trees, and stand on each other’s backs until they reach the branches.

When you meet a Puaka, it will attack if you move, and come to a halt if you stop. If it catches up with you, it will lick your bones clean. To lose the Puaka it is recommended to cross a stream; the creature may follow you across the stream, but once on dry land it will pause to lick itself dry, licking the flesh off its bones in the process.

“Puaka” and similar terms have meant pig in a number of languages – puaka in Rarotongan, Mangarevan, Rotuma, and Malay, vuaka in Fiji, puwaka in Malay, pua’a in Samoan, puaa in Tahitian, Marquesan, and Hawaiian, buaka in Tongan, and poaka in Maori. While this has been alternately compared to the Sanskrit sukara, the Latin porcus, and the English porker, the word seems to have had its own unique Polynesian origin. In some areas puaka has come to denote the pig-like demon; sometimes it loses its meaning as “pig” altogether, possibly due to the influence of Islam.

References

Mackenzie, D. A. (1930) Myths from Melanesia and Indonesia. Gresham Publishing Company, Ltd., London.

Boongurunguru

Variations: Bonguru

According to the mythology of the Solomon Islands, there was once a time when the waters flooded the Earth. This great flood, the Ruarua, engulfed all of the islands, even the 4,000 feet high San Cristoval hills; those drowned in it turned into stone pillars, which can still be seen at Mwata. It was Umaroa, leader of the Muara clan, who saved his people by taking them, a sacred stone, and pairs of all the animals on board a great canoe. When the waters receded, Umaroa made landfall at Waimarai in the Arosi district, and offered a sacrifice in thanks. From there an adaro descended from a rainbow and guided them to their new home.

Umaroa is now buried there, and his sacred stone was laid on top of him. The area is now rich with magic, and visitors have to observe certain rules to avoid bad luck. Any trees cut down and left there will cause the lumberjacks to wander in circles, always returning to the cut tree. If there is a rainbow above the river, it cannot be crossed without making an offering to the adaro first. Names have particular strength there; ropes cannot be called ari but instead must be referred to as kunikuni (“to let down”), otherwise snakes will be summoned immediately.

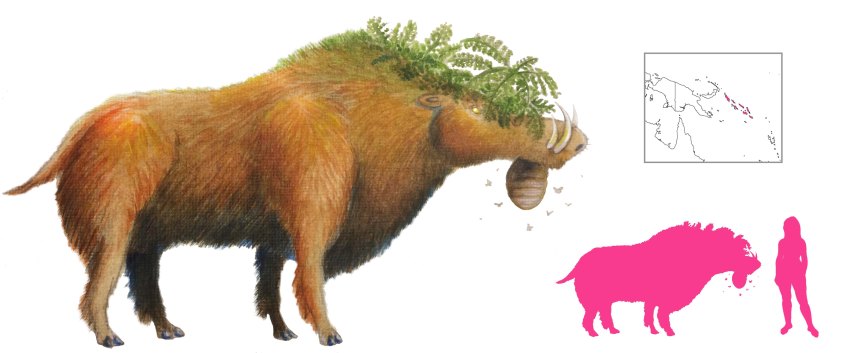

Of the spirits there, the most terrifying is Boongurunguru, the “pig-who-grunts”, the demon pig of Umaroa. He takes the form of a huge boar with ‘ama’ama ferns growing on his flattened head, and a buzzing nest of hornets located under his chin. He leads a herd of boars, all of them Boongurunguru, through the forest, goring and trampling anyone in their path. The appearance of a Boongurunguru foretells death; if the entire herd enters a village, everyone there will die. The boars get smaller and smaller as they approach a village, finally sneaking in at the size of mice, but they are no less deadly at that size.

If one hears Boongurunguru grunting and mentions that there must be pigs nearby, they are immediately surrounded by hundreds of venomous snakes – in front, behind, on either side, and falling out of the air.

This is because Boongurunguru has standards, and objects to being called a pig.

References

Fox, C. E. (1924) The Threshold of the Pacific. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Ltd., London; Alfred A. Knopf, New York

Mackenzie, D. A. (1930) Myths from Melanesia and Indonesia. Gresham Publishing Company, Ltd., London

Ragache, C. C. and Laverdet, M. (1991) Les animaux fantastiques. Hachette.