La Grande Encylopédie des Lutins/Fées/Elfes (The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries; The Complete Encyclopedia of Elves, Goblins, and other Little Creatures)

by Pierre Dubois, illustrations by Claudine and Roland Sabatier

The three encyclopedias written by Pierre Dubois and illustrated by Claudine and Roland Sabatier are a bit of a special case. As of writing this, there are 3 volumes, covering goblins, fairies, and elfs (respectively), but they are relatively little-known in the English-speaking world. Passable English translations are available, but the books have had an influence on French bestiaries in the same way Rose’s books have had in English – and that includes the mistakes too. I have a soft spot for these books – again, I read them cover to cover back in the day – but do they stand up to scrutiny today? Let’s find out.

Can be bought from Amazon in French here, here, and here, and in inferior English here and here.

Scope

The encyclopedias cover all sorts of magical beings but leave out the more “prosaic” creatures such as bonnacons and leucrotas. There is a marked tendency to favor humanoids above everything else, even when the creature in question isn’t humanoid (more on that below).

Otherwise, they cover a broad range of cultures across the world, with a strong focus on French creatures, giving them a niche that sets them apart.

Organization

Goblins, fairies, and elfs, but the distinction is vague and hazy at best. “Fairies”, for instance, includes basilisks and codrilles, valkyries and nagas. Chapters are by habitat: those of the Earth and caves, those of woods and forests, and so on.

The distinctions are arbitrary at best, but then that’s the author’s prerogative. Considering Dubois’ views on scholarship and classification, his categories come across as somewhat ironic.

Text

Florid, long-winded, pompous, purple, and fluffy. Dubois is a master at making mountains out of molehills, and creatures with summary descriptions are given extended biographies. For instance, the Duphon – literally the eagle owl, except it’s blamed for typical fairy behavior – is made into a sort of Knight Templar of the mountains by Dubois, with extended descriptions of its hunting habits and suicidal recklessness. None of this is corroborated in the primary literature.

Each creature gets a summary of vital statistics (size, habitat, food, activities, etc.) in the margins, which gives the book a further encyclopedic feel. These vital statistics are also often completely fabricated.

Dubois’ embellishment can take on rather uncomfortable tones. We really did not need to know what the pubic hair stylings are for the skogsra (thick) or the makralles (shaved). Nor is there an explanation for his alteration of some stories: the original tale of the girls and the pilous, for instance, ends with the girls shutting up and the pilous leaving, but Dubois makes the pilous stomp into the room, strip the girls naked, and force them to dance until exhaustion. There is no mention of the fact that vouivres get slain same as any other dragon. These modifications have no basis in the literature, which is cause for concern – not just for bad scholarship, but because they also say quite a bit about Dubois.

Images

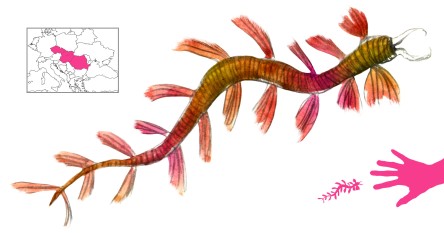

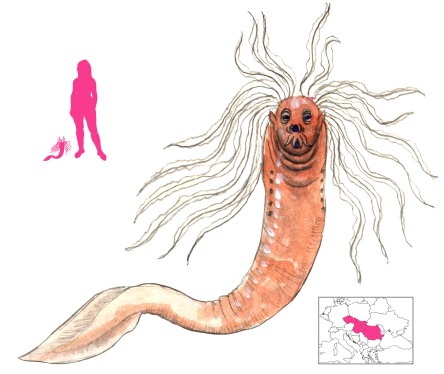

There have been complaints that the drawings are “childish” and “comic-booky” and “not serious enough”. I on the other hand have no such problem. The ink and paint drawings by the Sabatiers are easily some of the best selling points of the books, often conveying a setting without even showing the creature front and center. There are interesting takes on some creatures (the Yara-ma-yha-who and the Gremlin come to mind).

Any inaccurate depictions are ultimately Dubois’ fault, and I would not blame the Sabatiers for them.

Research

This is where I reserve most of my criticism, although it overlaps a bit with the text complaints. The fact that most of what Dubois writes about is obscure gives him free rein to invent anything he wants, and a lot of his inventions have been parroted by later authors, making it even harder to separate myth from, er, modern man-made myth. Dubois has also made it clear that he has nothing but scorn for research, study, academia, books… And it shows.

Creatures that are non-human are changed to become humanoid, often losing their best features in the process. The beefy-armed water-horse Mourioche becomes a goblin in a jester’s hat. The shapeless pilous become anthropomorphic dormice (to be fair, I liked that look enough to keep it for my pilou. I am part of the problem). The tourmentine and parisette plants become a goblin and fairy respectively, complete with backstory. The Rabelaisian coquecigrue bird becomes a tiny snake-fairy. The Breton tan noz will-o’-wisps become goblins. The list goes on and on.

Other creatures are fabricated out of whole cloth. The H’awouahoua has found its way into less critical bestiaries, even though this purported Algerian bogey has meaningless gibberish for a name. The Processionary, the Fougre, the Danthienne… The list of dubious creatures goes on, made worse by the difficulty of finding primary sources.

Dubois has also used a pseudonym, Petrus Barbygere (“Peter the Bearded”, i.e. himself), which he uses as a source for a number of citations. Whether this is amusing or not depends on who you ask, but it only muddies the mixture further.

Summary

There is a lot to fault in the Dubois encyclopedias, foremost being an attitude to research similar to that espoused by Attila the Hun. Once again, however, I can’t bring myself to lower the grade too much, as those books have nice drawings, obscure creatures, and helped set me on the track to finding out more.