Variations: Cockatrice, Basilisco, Basiliscos, Basiliscus, Basili-coc, Basilicok, Regulus (Small Prince), Codrille, Cocodrille, Cocadrille, Coquatrix, Harmena, Sibilus (Hisser), King of Serpents, Crested Crowing Cobra (potentially)

The Basilisk, the “little king” or “king of snakes”, is best known as a creature whose looks kill. Its primary claim to fame is a gaze that instantly kills anyone who sees it, or even anyone it looks at. The basilisk has appeared under a number of guises throughout the centuries, but there are at least a few constants. It is always deceptively small. It is a snake, or at least part snake, with or without rooster characteristics. It always has a crown – whether a white mark, a ring of hornlets, a rooster’s comb, or even a literal crown on its head. And finally, it is always extraordinarily virulent.

The basilisk is first and foremost a snake, born from the blood of Medusa as were all venomous snakes. It is found in the North African deserts – its very presence causes the desert, and it becomes frantic in the presence of water. At half a foot long, it is far from the biggest snake, but it is the king of snakes, traveling proudly with its head off the ground. It has a white spot or a crown on its head, and white markings down its back.

The basilisk is first and foremost a snake, born from the blood of Medusa as were all venomous snakes. It is found in the North African deserts – its very presence causes the desert, and it becomes frantic in the presence of water. At half a foot long, it is far from the biggest snake, but it is the king of snakes, traveling proudly with its head off the ground. It has a white spot or a crown on its head, and white markings down its back.

The exact nature of the basilisk’s deadliness is uncertain, as it is known to kill via venom, odor, and gaze. Murrus, one of Lucan’s soldiers, transfixed a basilisk with his spear, only to see the venom travel up his weapon and start corroding his hand. He survived by amputating his arm before the venom could reach his body. A basilisk can spit its venom skyward, frizzling up birds in flight. Its very gaze is deadly, as it can kill a man merely by looking at him with its gleaming red eyes. The regal nature of the basilisk and its propensity for projecting its venom suggest that cobras or spitting cobras were the origin of the legend.

Basilisks feared only three things: weasels, the crowing of roosters, and their own lethal gaze. The weasel was the only animal immune to the basilisk’s gaze and venom, making it the only natural predator of the king of snakes. Weasels were often sent into caves believed to harbor basilisks. This interaction also recalls that of the cobra and the mongoose. Basilisks also convulsed and died instantly upon hearing the crowing of a rooster. Travelers in the Libyan desert would be well advised to bring a rooster along with them. Topsell denied the possibility of basilisks perishing upon seeing each other, as “it is unpossible that any thing should hurt itself”; nonetheless, a basilisk in Vienna was killed by showing it a mirror.

With the passing of time the nature of the basilisk grew more and more confused. Various Biblical serpents were translated as basilisks. The basilisk gained more avian characteristics, including an origin in rooster eggs, and was confused with Cocodrillus (the crocodile); both of them were dangerous reptiles with small adversaries (the weasel for the basilisk, the hydrus for the crocodile). Further garbling of “cocodrillus” resulted in “cockatrice”. Wycliffe’s Bible had “cockatrice” as a translation of “basilisk”. Chaucer referred to the “basilicok”. With the accumulation of translation, grammar, and etymological errors, the basilisk (or cockatrice) became a hybrid of snake and rooster, with clawed wings, a rooster’s head, and a long serpentine tail (sometimes with an additional head at the end). This is the familiar cockatrice (or basilisk) of bestiaries, and an incarnation of the Devil himself. It further evolved into the alchemical cockatrice, holding its tail in its mouth, symbolizing the alchemical cycle and its mixed nature. The same nomenclatural confusion also gave rise to the Codrille, a basilisk from central France.

Despite efforts to separate the basilisk and the cockatrice – for example, making the basilisk a snake or lizard and the cockatrice a snake-rooster hybrid, or making them both snake-rooster hybrids, one with a snake head and the other with a rooster head – the fact remains that the names basilisk and cockatrice are interchangeable, and refer to the same animal. It is best to accept T. H. White’s statement that the cockatrice is “a medieval muddle” and leave it at that.

Cardano reported a basilisk found in the ruins of a demolished building in Milan. This particular specimen was wingless and featherless, with an egg-sized head that looked too large for its body. It had viper fangs, a bulky lizard-like body similar to that of the stellion, and only two stubby legs with catlike claws. The tail was as long as the body, with a swelling at its tip the size of the head. When standing up, it looked like a leathery, naked rooster.

Cardano reported a basilisk found in the ruins of a demolished building in Milan. This particular specimen was wingless and featherless, with an egg-sized head that looked too large for its body. It had viper fangs, a bulky lizard-like body similar to that of the stellion, and only two stubby legs with catlike claws. The tail was as long as the body, with a swelling at its tip the size of the head. When standing up, it looked like a leathery, naked rooster.

Aldrovandi was apparently inspired by this animal for one of his images of the basilisk, helpfully giving it six more legs. Based on the description and appearance, it appears to have been inspired somewhat by scorpions. Ironically, while this eight-legged depiction has proven particularly enduring, Aldrovandi himself was apparently doubtful of its authenticity, placing this presumed African creature just before a couple rays preserved in the shape of basilisks. The true, snake-like basilisk is given a full-page spread. Aldrovandi also produces a couple of purported basilisk eggs.

Flaubert, taking considerable creative liberties, describes the basilisk as a huge violet snake with a three-lobed crest and two teeth, one on each jaw. It speaks to Saint Anthony, warning him that “I drink fire. I am fire – and I breathe it in from mists, pebbles, dead trees, animal fur, the surface of swamps. My temperature sustains volcanos; I bring out the gleam of gems and the color of metals.”

Finally, Hichens’ “crowing crested cobra” of sub-Saharan Africa appears to be some kind of basilisk. It resembles a cobra, but with a crest on its head and the call of a rooster.

The life cycle of the basilisk is involved and complicated. The Egyptians believed it to be born from the egg of the ibis, while Neckham blames chickens. Basilisks are born from round shell-less eggs laid by old roosters in the summer (on a dungheap, in some accounts). Those eggs have to be incubated by a snake, a toad, or the rooster itself, eventually producing little terrors ready to kill at birth. As roosters may develop concretions that resemble eggs, and hens may look like roosters, any such fowl that seemed to be a male chicken laying an egg was immediately put to death. In 1474, one such heretical chicken was burned at the stake in Basle, in front of a large crowd.

The life cycle of the basilisk is involved and complicated. The Egyptians believed it to be born from the egg of the ibis, while Neckham blames chickens. Basilisks are born from round shell-less eggs laid by old roosters in the summer (on a dungheap, in some accounts). Those eggs have to be incubated by a snake, a toad, or the rooster itself, eventually producing little terrors ready to kill at birth. As roosters may develop concretions that resemble eggs, and hens may look like roosters, any such fowl that seemed to be a male chicken laying an egg was immediately put to death. In 1474, one such heretical chicken was burned at the stake in Basle, in front of a large crowd.

The only plant immune to the withering gaze of the basilisk is rue, which is consumed by weasels to protect themselves from their enemies. Remedies for basilisk envenomation will always contain rue. A dead basilisk will ward away spiders, and one such basilisk carcass in Diana’s temple kept swallows at bay.

Borges quotes Quevedo as giving the paradox of the basilisk: its existence cannot be proven, as anyone who sees it and survives is a liar, and anyone who sees it and dies will not tell the tale.

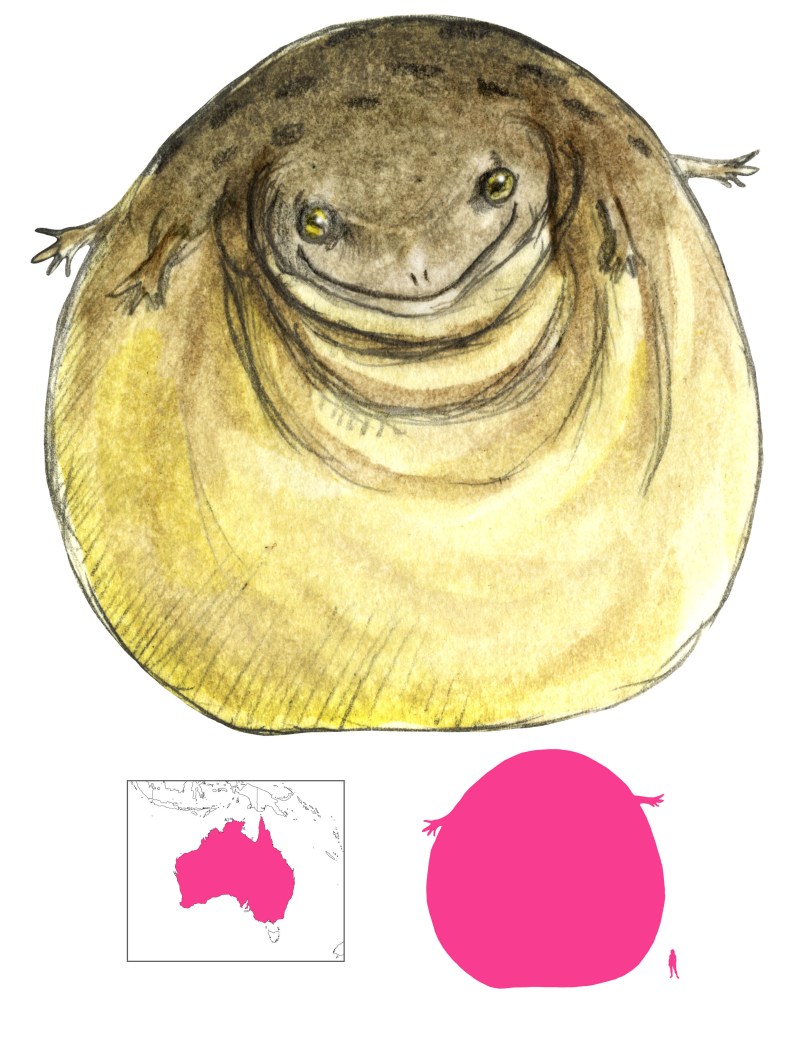

The basilisk of biology, or Jesus Christ Lizard (Basiliscus) is a completely harmless South American lizard, known for walking on water. The lethal powers of the basilisk were also transposed by European settlers onto rattlesnakes, and the Mexican West Coast rattlesnake still bears the name of Crotalus basiliscus.

References

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. I. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Aldrovandi, U. (1640) Serpentum, et Draconum Historiae. Antonij Bernie, Bologna.

Barber, R. (1993) Bestiary. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Breiner, L. A. (1979) The Career of the Cockatrice. Isis, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 30-47.

Breiner, L. A. (1979) Herbert’s Cockatrice. Modern Philology, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 10-17.

Brown, T. (1658) Pseudodoxia Epidemica. Edward Dod, London.

Bulfinch, T. (1997) The Age of Fable. Macmillan, New York.

Cardano, G.; le Blanc, R. trans. (1556) Les Livres de Hierome Cardanus Médecin Milannois. Guillaume le Noir, Paris.

Evans, E. P. (1987) The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals. Faber and Faber, London.

Flaubert, G. (1885) La Tentation de Saint Antoine. Quantin, Paris.

Hargreaves, J. (1983) The Dragon Hunter’s Handbook. Armada.

Hichens, W. (1937) African Mystery Beasts. Discovery (Dec): 369-373.

Isidore of Seville, trans. Barney, S. A.; Lewis, W. J.; Beach, J. A.; and Berghof, O. (2006) The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lemnius, L. (1658) The Secret Miracles of Nature. Jo. Streater, London.

Liss, A. R. (1987) A Basilisk by Any Other Name… Teratology 35, pp. 277-279.

Lucan, trans. Rowe, N. (1720) Pharsalia. T. Johnson, London.

Pliny; Holland, P. trans. (1847) Pliny’s Natural History. George Barclay, Castle Street, Leicester Square.

de la Salle, L. (1875) Croyances et légendes du centre de la France, Tome Premier. Chaix et Cie., Paris.

Sax, B. (1994) The Basilisk and Rattlesnake, or a European Monster Comes to America. Society and Animals, vol. 2, no. 1.

Topsell, E. (1658) The History of Serpents. E. Cotes, London.

White, T. H. (1984) The Book of Beasts. Dover Publications, New York.