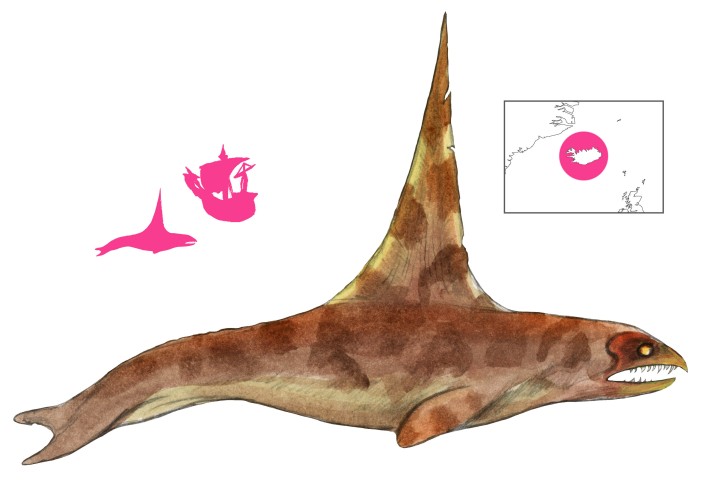

Variations: Sverdhvalur, Sword-whale, Swordwhale; Sverðfiskur, Sverðfiskar, Sverðfiskr (Sword-fish); Sverðurinn (Sworder); Brúnfiskur, Brún-fiskur (Brown-fish); Sveifarfiskur (Crank-fish); Slambakur (Slap-whale); Staurhvalur (Stump-whale); Einbægslingur (One-fin); Haskerðingur (High-Fin; potentially the basking shark or the swordwhale); Killer Whale, Orca, Swordfish

The Sverðhvalur (“Swordwhale”) or Sverðfiskur (“Swordfish”) is one of the illhveli, or “evil whales” that lurk off the coast of Iceland. Like the other evil whales, it is unfit for eating, and the steypireyður or blue whale is its mortal enemy.

The sverðhvalur’s most distinctive feature is the sharp bony fin growing out of its back. This fin is 3-12 cubits (1.5-6 meters) tall. The sverðhvalur is about the size of a sperm whale at the largest, and its spouting is short and heavy. Its face is owlish in appearance, with a pointed snout and a large mouth set with vicious teeth. If the brúnfiskur (“brown-fish”) is one of its many aliases, it can be assumed to be brown in color, but another account describes it as grey.

The sverðhvalur is a fast swimmer, and beats the water on either side of it with its fin when agitated. It is often accompanied by a smaller whale – perhaps its offspring – that swims under its pectoral fin and feeds on its scraps. The bladed dorsal fin is used as a weapon, and a sverðhvalur will swim underneath good whales to cut their bellies open with crisscross slashes. Whales will beach themselves rather than suffer a sverðhvalur’s attack. Sverðhvalurs are also wasteful eaters, choosing to eat only the tongue of cetacean prey and leaving the rest to rot. Boats are treated in the same way as whales are, with the dorsal fin punching holes through hulls or slicing cleanly through smaller boats and sailors alike.

Other encounters, especially with larger vessels, are more harmful for the whale. A trading ship sailing from eastern Iceland to Copenhagen came to a stop in the middle of a large pod of whales, and suddenly felt a strong tug coming from below. When the ship moored in Copenhagen, a large fish’s tusk was found sticking out of the hull.

Another sverðfiskur followed a boat off Eyjafjörður, and gave up the chase only after a gun was fired into its gaping mouth.

The term sverðfiskur or sverðfiskr (“sword-fish”) has been used to refer to the swordfish, the sawfish, and the killer whale. The basking shark and the killer whale have also been accused of slicing through ships and eviscerating whales with their fins, and it is the killer whale or “swordwhale” that appears to be the sverðhvalur’s ancestor.

References

Anderson, P. (1955) Bibliography of Scandinavian Philology XXIV. Acta Philologica Scandinavica, Ejnar Munksgaard, Copenhagen.

Árnason, J.; Powell, G. E. J. and Magnússon, E. trans. (1866) Icelandic Legends, Second Series. Longmans, Green, and Co., London.

Davidsson, O. (1900) The Folk-lore of Icelandic Fishes. The Scottish Review, October, pp. 312-332.

Hermansson, H. (1924) Jon Gudmundsson and his Natural History of Iceland. Islandica, Cornell University Library, Ithaca.

Hlidberg, J. B. and Aegisson, S.; McQueen, F. J. M. and Kjartansson, R., trans. (2011) Meeting with Monsters. JPV utgafa, Reykjavik.