Variations: Amphisbaina, Alchismus, Amphisilene, Amphistere, Amphiptere, Ankesime, Auksimem, Double-head, Double-marcheur (French); Doble Andadora; Blind Snake

The Amphisbaena, “goes both ways”, is one of the many snakes encountered by Lucan and his army in the deserts of Libya. It has also been reported from Lemnus, but it is unknown to the Germans. Unlike its biological namesake, the benign, legless burrowing lizards known as amphisbaenas, the Libyan amphisbaena is venomous and deadly, producing double the amount of venom a regular snake would. Sand boas are another candidate for the amphisbaena’s identity, but they too are harmless.

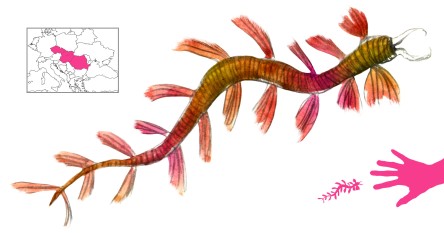

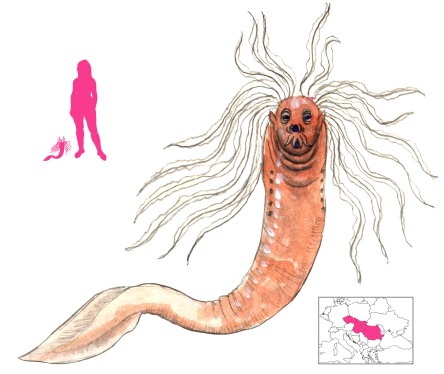

Two heads are an amphisbaena’s distinguishing feature, with one head in the normal place and one at the end of the tail. How these heads affect locomotion is unclear. An amphisbaena may move like a regular snake, one head trailing behind, but changing directions instantly and going forward or backwards with equal ease. Alternatively, both heads could lead, leaving the body following behind in a loop. An amphisbaena’s sight is poor, but its eyes glow. Physically it resembles an earthworm, with an indistinguishable head and tail. It is blackish earth-colored, with a rough, spotted skin. It is very muscular and tough-scaled, and is an excellent digger.

In addition to the amphisbaena described above, Pammenes tells of two-headed snakes with two feet near the tail in Egypt. Borges reports a creature from the Antilles called the doble andadora (“goes both ways”), also known as the two-headed snake and the mother of ants. It feeds on ants and can reattach itself if chopped in half. The association with ants is the same as that of the legless lizards that share the amphisbaena’s name, and probably refers to the same animal. As with every other snake, the amphisbaena of medieval bestiaries was burdened with legs and wings, and the use of the term became even more confused. Any creature in medieval art with an extra head on the end of its tail can be safely labeled an amphisbaena, although at this point the Greek two-headed snake is long forgotten. The heraldic amphisbaena eventually was corrupted into amphistere, amphiptere, and amphisian basilisk, from where it was assumed to have a pair of wings as well as an extra head!

Amphisbaenas are very cold-resistant, and are the first snakes to come out after winter, ahead of the first cuckoo song. Their temperament is correspondingly hotter than that of other snakes. They feed on earthworms, beetles, and especially ants, digging into their nests, its tough skin protecting it from their bites and stings. Solinus believed amphisbaenas gave birth through the tail-end mouth. They take good care of their eggs, guarding them until they hatch and showing love to their offspring.

Amphisbaena venom is unremarkable and causes the same symptoms as viper bites – inflammation and slow, painful death. Besides drinking coriander, the antidotes for amphisbaena bite are the same as those used for vipers. Amphisbaenas themselves are hard to kill, except with a vine-branch. One amphisbaena woke Dionysus from his rest, and in retaliation he crushed it with a vine-branch.

Several remedies have been derived from amphisbaenas. A walking-stick covered with amphisbaena skin keeps away venomous animals, and an olive branch wrapped in amphisbaena skin cures cold shiverings. An amphisbaena attached to a tree will ensure that the logger will not get cold and the tree will fall easily. If a pregnant woman steps over a dead amphisbaena, she will abort instantly, as the vapor arising from the dead snake is so toxic as to suffocate the fetus. However, if a pregnant woman carries a live amphisbaena in a box with her, the effect is nullified.

The two heads of the amphisbaena understandably led to a healthy amount of criticism. Thomas Browne denied that amphisbaenas could exist, stating that an animal with two anteriors was impossible. Al-Jahiz recounts an interview with a man who swore that he saw an amphisbaena, and, unconvinced, chalked it up to fear-induced exaggeration. “From which end does it move?” he asked the man. “Where does it eat from, and where does it bite from?” The man replied “It doesn’t move forward, but it gets around by rolling, like boys roll on sand. As for eating, it eats lunch with one head and dinner with the other. And as for biting, it bites with both heads at the same time!”

References

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. II. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Aelian, trans. Scholfield, A. F. (1959) On the Characteristics of Animals, vol. III. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Aldrovandi, U. (1640) Serpentum, et Draconum Historiae. Antonij Bernie, Bologna.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris.

Druce, G. C. (1910) The Amphisbaena and its Connexions in Ecclesiastical Art and Architecture. Archaeological Journal, v. 67, pp. 285-317.

Isidore of Seville, trans. Barney, S. A.; Lewis, W. J.; Beach, J. A.; and Berghof, O. (2006) The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Al-Jahiz, A. (1966) Kitab al-Hayawan. Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi wa Awladihi, Egypt.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Lucan, trans. Rowe, N. (1720) Pharsalia. T. Johnson, London.

Macloc, J. (1820) A Natural History of all the Most Remarkable Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes, Serpents, Reptiles, and Insects in the Known World. Dean and Munday, London.

Palliot, P. (1660) La Vraye et Parfaite Science des Armoiries. Pierre Palliot, Dijon.

Parker, J. (1894) A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. James Parker and Co., Oxford.

Pliny; Bostock, J. and Riley, H. T. trans. (1857) The Natural History of Pliny, v. III. Henry G. Bohn, London.

Topsell, E. (1658) The History of Serpents. E. Cotes, London.