Variations: Teel get, Teelgeth, Delgeth

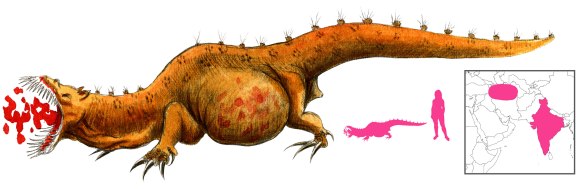

As one of the Anaye, the “Alien Gods” of Navajo folklore, Teelget was born from a human woman who resorted to unnatural and evil practices. In this case, his “father” was an antler. The creature born was round, hairy, and headless, and was cast away in horror; it was this creature that grew into the monster known as Teelget.

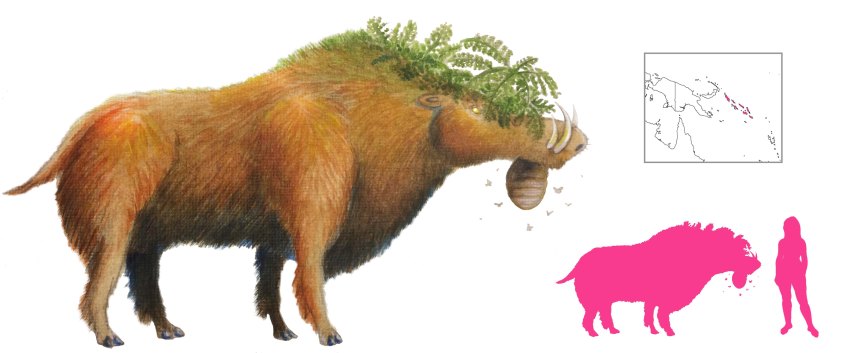

The origin of Teelget’s name is not known with certainty, but the “tê” makes reference to his horns. He is like an enormous, headless elk or antelope, rounded in shape, hairy like a gopher, with antlers he uses as deadly weapons. Coyote was his spy, and between him and the other Anaye they laid waste to the land, slaughtering many.

It was Nayenezgani, “Slayer of Alien Gods”, who finally put an end to Teelget’s reign of terror. Armed with his lightning arrows, the hero tracked Teelget down, finding the monster resting in the middle of a wide open plain.

How was Nayenezgani to sneak up on Teelget without being noticed? The grass offered no cover, and Teelget was sure to detect him and retaliate. As he considered his options, he was greeted by Gopher. “Why are you here?” said Gopher. “Nobody comes here, for all are afraid of Teelget”. When Nayenezgani explained that he was here to destroy Teelget, Gopher was more than happy to help. He said that he could provide a way to reach Teelget, and all he asked for as payment was the monster’s hide.

Gopher then excavated a tunnel that led right under the sleeping Teelget’s heart, and dug four tunnels – north, south, east, and west – for Nayenezgani to hide in after Teelget woke up. He even gnawed off the hair near Teelget’s heart, under the pretext that he needed it to line his nest.

That was all Nayenezgani needed. He crawled to the end of the tunnel and fired a chain-lightning arrow into Teelget’s heart, then ducked into the east tunnel. Enraged and in agony, Teelget gouged the east tunnel open with his antlers, only to find that Nayenezgani had moved to the south tunnel. He destroyed that, then the west tunnel, but he only managed to put an antler into the north tunnel before succumbing to his injury.

Nayenezgani couldn’t tell if Teelget had died or not, so Ground Squirrel volunteered to inspect. “Teelget never pays attention to me”, he explained. “If he is dead, I will dance and sing on his antlers”. Sure enough, Ground Squirrel celebrated on top of the fallen monster, and painted his face with Teelget’s blood; ground squirrels still have streaks on their face after that day. In some retellings Chipmunk fills this role, painting stripes down his back.

A chunk of antler and a piece of liver were taken by Nayenezgani as trophies, but Gopher went to work at once skinning Teelget. “I will wear his skin, so that when humans increase once more, they will be reminded of Teelget’s appearance”. And to this day, rounded, hairy gophers still wear the skin that Teelget once wore.

References

Alexander, H. B. (1916) The Mythology of All Races v. X: North American. Marshall Jones Company, Boston.

Locke, R. F. (1990) Sweet Salt: Navajo folktales and mythology. Roundtable Publishing Company, Santa Monica.

Matthews, W. (1897) Navaho legends. Houghton Mifflin and Company, New York.

O’Bryan, A. (1956) The Diné: Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians. Bulletin 163 of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.