Variations: Kalydonian Boar

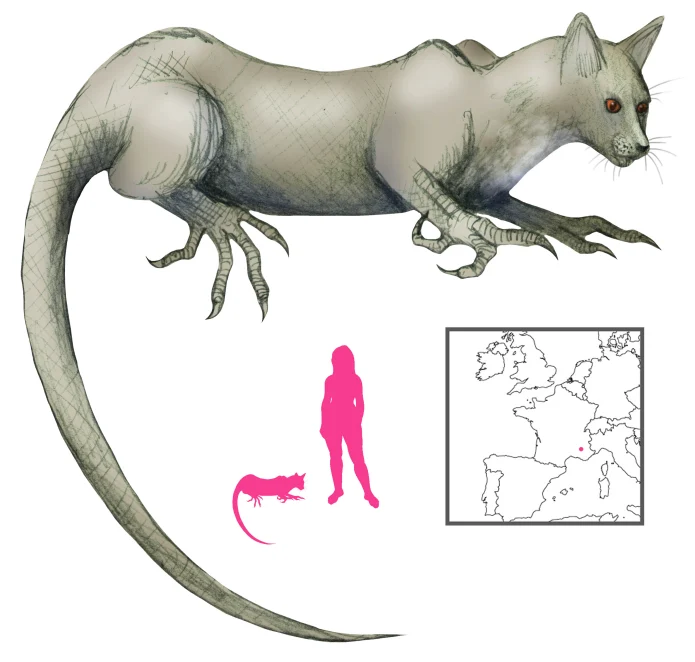

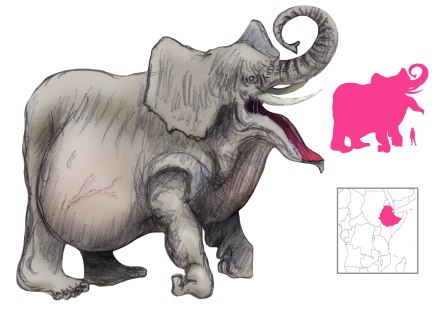

The tragedy of the Calydonian Boar started when King Oineus of Calydon made a sacrifice of firstfruits that left out Artemis. The vengeful goddess sent a monstrous boar to ravage Aitolia. This Calydonian boar was the size of a bull, with red eyes, a high stiff neck with bristles rising like spears, tusks as big as an elephant’s, and fire and lightning flashing from its mouth. It gored people and livestock, plundered the crops, burned the fields, and ruined the harvest.

Oineus begged all the heroes of Greece to save him from the boar. They responded. The team that was formed to hunt the boar included Oineus’ son Meleager, the twins Castor and Polydeuces, Theseus of Athens, Jason of Iolcos, Iphicles of Thebes, Eurytion of Phthia, and Atalanta of Arcadia, among many others. The presence of Atalanta, a woman and a skilled hunter, ruffled a few feathers; some of the men thought it beneath them to hunt with her. Meleager made sure to silence dissent before heading out to find the boar.

Althaia, mother of Meleager and wife of Oineus, watched her son leave without fear. Why would she be afraid for his life? Did the Moirai not foretell that he would only die once a certain log was burnt up – a log that she kept safely locked away in a chest? What could the boar possibly do to him? Her brothers, the sons of Thestios, also went with the party, but she had faith that nobody would come to harm.

It wasn’t hard to find the Calydonian boar. Its spoor was a wake of death and destruction. The sight of the hunting party drove the boar into a furious rage, and the hunters quickly became the hunted. Enaesimus tried to turn and run, but was hamstrung. Nestor narrowly escaped death by using his spear to pole-vault to safety. Hippasus’ thigh was gashed open. Peleus accidentally killed Eurytion with his javelin in the heat of battle. It was Atalanta that drew first blood with an arrow behind the boar’s ear, an action that earned Ancaios’ scorn. “A man’s weapons will always be better than a girl’s! Watch this!” Ancaios hefted his axe just in time to get disemboweled by the boar. Finally Meleager himself stabbed the boar’s flank, killing it.

In due course the boar was skinned and its magnificent hide taken, to be offered to the most valorous of the party. Meleager gave it to Atalanta without hesitation. The sons of Thestios, his uncles, were furious. “A mere woman does not deserve such a prize”, they grumbled. “If Meleager won’t take it, it is ours by right”. Tempers flared. The uncles took the skin by force, provoking Meleager to draw his sword and kill both of them.

Althaia did not take the news well. When she heard her brothers were dead, she seized Meleager’s log and tossed it into the fire in a fit of rage. Meleager was burned up from within and died in agony, envying Ancaios’ swift death at the boar’s tusks. Althaia went on to kill herself in a fit of conscience. Meleager’s sisters wept bitterly until Artemis transformed all but two of them into guineafowl.

So it goes.

References

Buxton, R. (2004) The Complete World of Greek Mythology. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

Ovid, Humphries, R. trans. (1955) Metamorphoses. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Smith, R. S. and Trzaskoma, S. M. (2007) Apollodorus’ Library and Hyginus’ Fabulae. Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis.