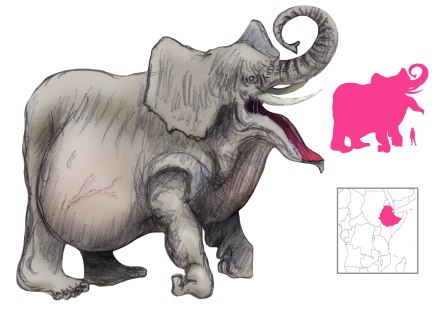

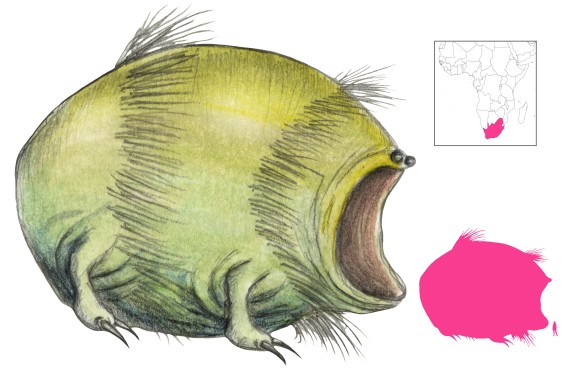

Variations: Kadindi, Kaddodi, Kadda, Swallower-of-Men

The Dodo is a monstrous humanoid creature from the folklore of the Hausa people. He can be found lurking in the deep forests and swamps of sub-Saharan West Africa, with a range including Sudan, Ghana, Nigeria, and the Côte d’Ivoire. The dodo has nothing in common with the extinct flightless bird of the same name, and probably was derived from tales of giant snakes.

Not much is known about a dodo’s appearance. He – for the dodo is always male – is the King of Beasts, and can just as easily be the lion, the python, the elephant, or the rhinoceros. A dodo is humanoid in appearance and large in size, as he has to stoop to get through doors. He has long, shaggy black hair. He has a keen sense of smell, and can detect meat from far away. He has some degree of magic powers, but cannot cross running water (paradoxically, dodos also live in ponds and streams). Most importantly, the dodo has a vast mouth glowing red from the inside, a seemingly infinite stomach capacity, and a taste for human flesh. As one of the African “swallowing monsters”, a dodo can easily engulf an entire village.

A dodo is often a self-invited guest, eating more and more until there is nothing left. This is not always a bad thing. Once a miser and his son were preparing to butcher a freshly-slaughtered ox in the forest, far from prying eyes. They decided to cook it in a nearby fire – a fire which turned out to be a dodo’s glowing, cavernous mouth.

“Well well”, said the dodo. “Who has invited me?” The miser, hoping to placate him, said “I did!” and gave him a leg of beef, which the dodo put away in his bag. “Does a man invite a friend to a feast for such a small morsel?” said the dodo. In response, the miser gave him another leg. “Does a man invite a friend to a feast for such a small morsel?” The next two legs followed, then half the bull, then the remainder of the bull. “Does a man invite a friend to a feast for such a small morsel?” “But there is nothing left!” protested the man. “You are also meat”, came the response. Terrified, the miser shoved his son forward, and the dodo tossed him into his bag. Finally, he grabbed the miser himself. “What about you?” he said, throwing him into his bag as well. The dodo went to collect firewood, but in the meantime the father and son managed to cut their way out of the bag and made their escape. The dodo returned, shrugged, and got a meal of roast beef. The miser vowed he would never be greedy again, and devoted the rest of his life to sharing his food and wealth with others.

While dodos readily eat meat, they are also fond of taking human women as their wives, sometimes fathering repulsive half-dodo children with them. Dodos like to strike bargains with prospective spouses, promising to help them for the price of marriage; sometimes those “bargains” are more straightforward, consisting of “Would you like me to eat you or marry you?” Such unions are never happy, and the wife will always try to escape her captor.

One dodo story tells of a young woman, pregnant with her first child, drawing water from a stream. Another woman, jealous of her companion and looking to get her scolded, threw dirt in her pot before leaving. But as the pregnant woman tried to carry her water pot, a dodo came out of the water and helped her with her load. Before she could protest, he stated “If you give birth to a boy, he will be my friend. If your child is a girl, she will be my wife”. And with that, he disappeared back into the water.

The mother soon gave birth, and her jealous rival was prompt to report the news to the dodo. “She gave birth to a girl”, she announced, and the dodo was immensely pleased. He was content to wait over the years, until the girl had become a woman as beautiful as her mother. On the day of the girl’s wedding, the jealous woman once more reported the news to the dodo, and he decided to show up uninvited.

“Kadindi has arrived”, he boomed, as everyone stared at him. “I have come to collect the payment I am due”. The daughter was obviously unhappy about marrying the monster, so instead her father gave the dodo a horse, part of the bride’s dowry. “Here is the payment for your debt”, he said, and the dodo swallowed the horse. But that was not enough. Next he ate all of the cattle, all of the wedding feast, all of the guests, and finally the father and mother. There was only the daughter left, and in desperation she prayed to the heavens. “Dodo has come to demand payment”, she implored. In response to her prayer, a knife fell out of the sky, and it was promptly swallowed as well – killing the dodo, cutting open his belly, and causing all the livestock, food, guests, and parents to come out unharmed. The wedding went on as planned.

References

Tremearne, A. J. N. (1913) Hausa Superstitions and Customs. J. Bale and Sons and Danielsson, Ltd., London.