Variations: Rauðkembingur, Raudkembingr, Rauðkembingr, Raudkempingur, Red-comb, Red-crest; Raudkembir (Red-crester); Raudkinni (Red-cheek); Raudkinnung, Raudkinnungur (Red-cheeker); Raudgrani (Red-snout); Raudhofdi (Redhead); Kembingur (Crest); Kembir (Crester); Faxi (Maned)

Of all the illhveli, or evil whales that ply Icelandic waters, the Raudkembingur (“red comb” or “red crest”) is the most savage and bloodthirsty. It may not have the size or raw power of some of the other whales, but it is unmatched in ferocity and determination to harm boats. As with all illhveli, the raudkembingur is an abomination, and eating its inedible flesh is forbidden. Boiling its meat causes it to disappear from the pot.

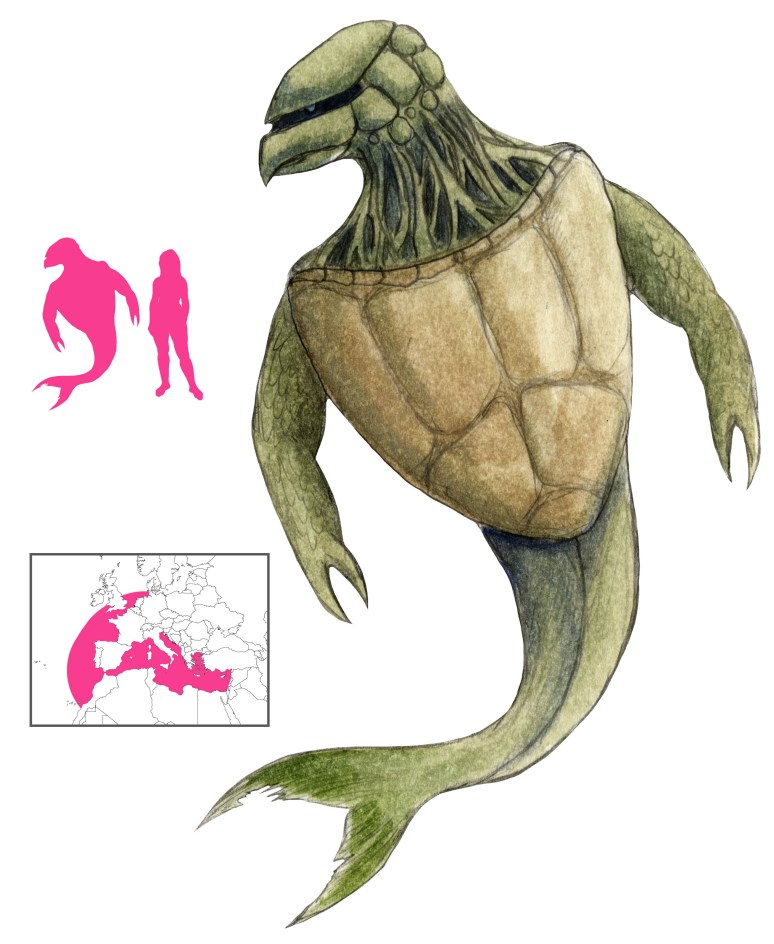

The nature of the red comb or crest that gives the raudkembingur its name is unclear. Accounts refer to a crest of bristly hair, a mane like a horse, or even a row of finlets; its extent varies from depiction to depiction, but Jon Gudmundsson restricts it to the neck. The crest is a bright red on a coffee-brown body with a pink belly; other accounts say it is reddish all over, or has red cheeks or a red head. Sometimes there are red streaks from the mouth to the trunk, as if drawn in blood. The head itself, as depicted by Gudmundsson, is almost saurian in appearance, with sharp teeth in both jaws. It either has a small dorsal fin or none at all.

Raudkembingurs grow to twenty to forty cubits (10-20 m) in length. They are elongate, streamlined, and very fast swimmers. Their movement is accompanied by massive amounts of foam and the whale’s ominous neighing. This, along with the red mane, makes the raudkembingur confusable with the hrosshvalur, and the two have become interchangeable over time. Hrosshvalurs, however, can be easily distinguished by their dappled coloration, horse’s tail, and enormous eyes.

There is no limit to the malice and evil of the raudkembingur. Its mere presence is enough to dissuade fishermen from an area. It will play dead for half a month, floating innocuously on the surface of the water until someone is foolish enough to approach it. Once a boat is within range, the whale puts its bulk and teeth to use, leaping onto the vessel, destroying it, and drowning all aboard. Much like a shark is followed by pilotfish, the raudkembingur regularly has a beluga whales or narwhals (nahvalur – “corpse whale”) following in its wake. These smaller, harmless whales clean up after the raudkembingur and eat its plentiful leftovers.

If anything, the whale’s single-minded love of destruction represents the best hope of foiling it. If a boat escapes it, and it does not destroy another within the same day, it will die of frustration. One raudkembingur destroyed eighteen boats in the course of one day, but a nineteenth boat managed to escape by dressing a piece of wood in clothes and tossing it overboard. The raudkembingur, believing it to be a human, kept trying fruitlessly to drown it while the boat made its escape.

Raudkembingurs will also overexert themselves to death when pursuing prey. A boat captained by Eyvindur Jónsson off Fljót ran into a raudkembingur, and the crewmen reacted by rowing for land as fast as possible until they reached safety at the inlet of Saudanesvik. The sea then turned red as the raudkembingur breathed its last. The boat itself earned the nickname of Hafrenningur (Ocean Runner) after this feat.

Like the hrosshvalur, the demonic raudkembingur is also associated with sorcery and metamorphoses. One tale tells of a callous young man at Hvalsnes who was cursed by the elfs into becoming a monstrous red-headed whale. He wreaked havoc in Faxafjord and Hvalfjordur, until he tried to chase a priest up-river. The red-head died of exhaustion in Hvalvatn Lake, and its bones can still be seen there.

It is generally believed that the raudkembingur and hrosshvalur are monstrous aggrandizements of the walrus (itself derived from hvalhross – “whale-horse”). If the walrus is indeed the origin, however, it has become fully dissociated from its descendants. Gudmundsson realistically depicts both the walrus and the two illhveli, making it very clear that the latter are indeed whales. Otto Fabricius believed the raudkembingur to be inspired by the maned Steller’s sea lion, all the way from Kamchatka.

References

Arnason, J.; Powell, G. E. J. and Magnusson, E. trans. (1864) Icelandic Legends. Richard Bentley, London.

Davidsson, O. (1900) The Folk-lore of Icelandic Fishes. The Scottish Review, October, pp. 312-332.

Fraser, F. C. An Early 17th Century Record of the Californian Grey Whale in Icelandic Waters. In Pilleri, G. (1970) Investigations on Cetacea, vol. II. Benteli AG, Bern.

Hermansson, H. (1924) Jon Gudmundsson and his Natural History of Iceland. Islandica, Cornell University Library, Ithaca.

Hlidberg, J. B. and Aegisson, S.; McQueen, F. J. M. and Kjartansson, R., trans. (2011) Meeting with Monsters. JPV utgafa, Reykjavik.

Kapel, F. O. (2005) Otto Fabricius and the Seals of Greenland. Meddelelser om Grønland Bioscience, Copenhagen.

Larson, L. M. (1917) The King’s Mirror. Twayne Publishers Inc., New York.