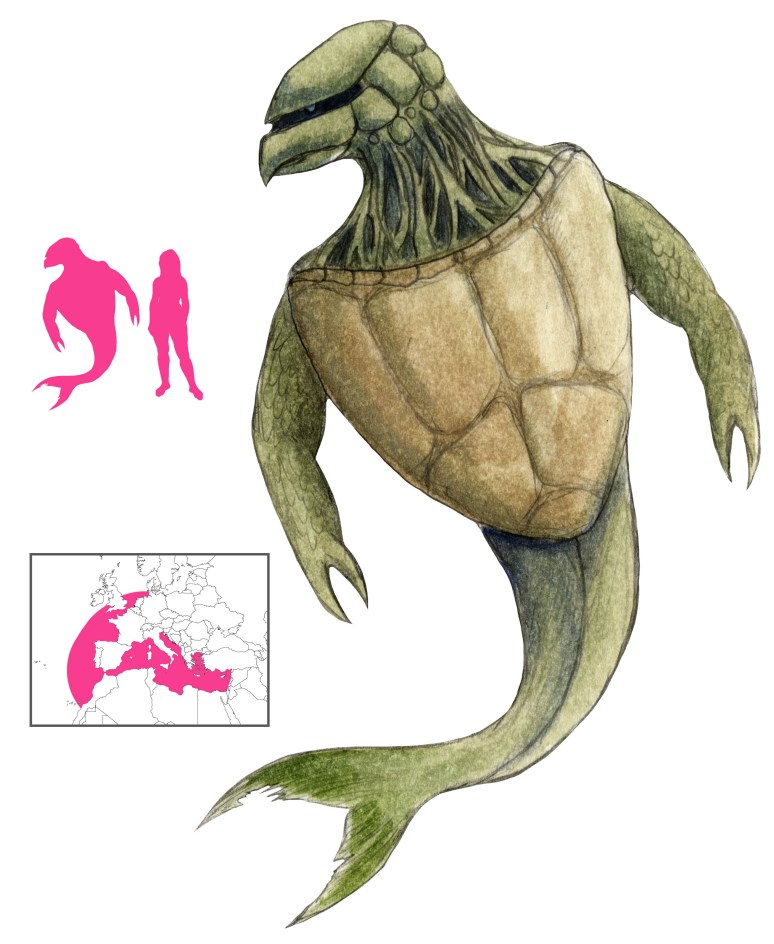

Variations: Tsemaus, Chemouse, Narhnarem-tsemaus, Snag, Supernatural Snag, Tsem’aus, Tcamaos, Tca’maos, Tidewalker, Ts’um’os, Tsamaos, Kanem Ktsem’aus; Weegyet, Wi’git

The Tsemaus (“Snag”) or Narhnarem-Tsemaus (“Supernatural Snag”) is the personification of river snags., floating logs, and other hazards of the water. It is found in the folklore and art of the Pacific Northwest, notably in Tsimshian and Haida culture around the mouth of the Skeena River.

One of its names, Wi’git or Weegyet, connects it to Raven the trickster, and it is one of his many forms. The creator and trickster Nanki’islas also assumed the form of a tsemaus after he was done.

A tsemaus can vary a lot in appearance, much like the driftwood it imitates, but it almost always has a snag for a dorsal fin – or is itself a snag. It can be as simple as a dead log with a tail that can swim against the current. It can be a huge sea lion with dorsal fins and blowholes, or an enormous grizzly bear with a downturned mouth like a dogfish and two sharp snags protruding from its back, with or without one or more sharp fins of a killer whale. It can be a hybrid of bear and killer whale, or raven and killer whale, with multiple bodies. It can be a large frog covered in seaweed with a snag sticking out of its back, and can even be a canoe or a schooner. Meurger states that it can cleave swimmers with its fin.

The tsemaus uses its fin to destroy boats. It has no problem swimming upstream and plowing through log jams. If angered it breaches and lands on canoes, smashing them to bits, or makes huge waves to capsize boats. It drowns people, who then become killer whales.

It is found as a crest on the totem poles of the coastal clans.

References

Barbeau, M. (1950) Totem poles. Bulletin No. 119, Anthropological Series No. 30, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa.

Barbeau, M. (1953) Haida Myths Illustrated in Argillite Carvings. Bulletin No. 127, Anthropological Series No. 32, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa.

Boas, F. (1951) Primitive Art. Capitol Publishing Company, New York.

Deans, J. (1893) Totem Posts at the World’s Fair. The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal, Vol. XV, No. 4, pp. 281-286.

Meurger, M. (1988) Lake Monster Traditions: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Fortean Tomes, London.

Swanton, J. R. (1909) Contributions of the Ethnology of the Haida. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. VIII.