You may be reading A Book of Creatures, but have you considered reading other books of creatures? Perhaps you just finished reading The Crystal Witch’s Encyclopedia of Elemental Birds and Beasts and are wondering whether or not it’s adequately researched? Or maybe you’re just one of my annoying fans convinced that I have the last word to say about mythical creatures? (I do) Your sleepless nights are over, as today’s Wednesday Interlude brings us the recurring feature of book reviews. In the thorough ABC style you’ve come know and love, the reviews will address everything a monster hunter would find important. And what better way to start than with Carol Rose’s Giants, Monsters & Dragons? Check it out on Amazon, and on Alibris.

Do note that all comments on Giants, Monsters & Dragons apply equally to its companion book Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns and Goblins.

Giants, Monsters & Dragons

by Carol Rose

Giants, Monsters & Dragons (GMD from here on) is about as close as you can get to a cornerstone of modern bestiaries. No other book is as influential, having served as the basis for countless pages of online information and leading to the popularization of many obscure creatures. It is not, however, without its faults, as we shall soon see.

Scope

GMD aims to cover a dizzying array of creatures, by and large “monstrous”, with the more humanoid entities covered in Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns and Goblins. Rose outlines the criteria at the beginning as 1) the creature must not be divine or have divine powers, and 2) must be mythological, folkloric, or have some supernatural origin. Of course, no classification scheme is perfect, and this includes such entries for Titans (surely on the rank of gods?) and creatures from popular modern fiction such as Olog-hai – neither of which will make it anywhere in ABC.

What is undeniable is the vast amount of creatures on offer. The best-represented are English, Classical, and United States “Fearsome Critters”, but the book spans the globe, bringing in the Mi-ni-wa-tu and the Cheeroonear alike. For many of us, this is the first time we came across the Butatsch Cun Ilgs and the Carcolh, even if they were misnamed. Rose has done an amazing job putting this menagerie between two covers, and so the quantity – if not the quality – is exemplary.

Organization

GMD is organized by alphabetical order, which is a safe, standard choice for an encyclopedia. The entries are connected to the numbered bibliography and are amply cross-referenced, although some entries could do with a bit more referencing beyond “monster”. There are extensive appendices organizing creature by locality and general type as well, making GMD very user-friendly.

Text

Rose’s text is factual and academic, with little in the way of amusing asides or artistic flourishes. Entries start with “X is the name of a…” This is not a criticism; this format of writing, while lacking in poetry, is perfect for a serious encyclopedic volume, while other books overdo the florid descriptions.

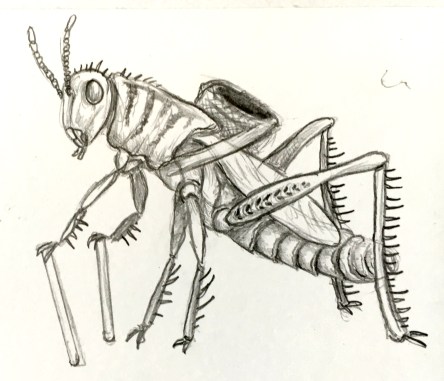

Images

The illustrations are all black and white, copyright-expired type pictures. They are not especially evocative or interpretive, but do a good job of showing what people at the time thought. At their best when actually depicting the creature in question (e.g. the Aloés on page 14), they are at their worst when used as generics for something much weirder (e.g. “Sea serpents much like the fearsome Muirdris” on page 259, or the unicorn giant for the Aeternae on page 5). As with the text, I have no problem with any of this, and they work just fine for an encyclopedic work. What does bother me is the lack of attribution for the images beyond “Scala Art Resource” or the like, and the lack of original context.

Research

This is where my primary criticisms come in. As an English author, Rose is (as are most bestiary writers) necessarily biased towards English-language creatures. Non-English creatures can end up with butchered names, such as the retention of superfluous definite articles in “lou carcolh” and “al-mi’raj”, the use of “djinn” in the singular (and the separation of “djinn” and “jinn”), and the painful mangling of “angka”. Others are harder to pinpoint, such as “butatsch cun ilgs” becoming “butatsch-ah-ilgs”.

GMD’s bibliography clocks in at almost 200 references, but many are themselves compilation bestiaries, such as Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings, Barber and Riches’ Dictionary or Meurger and Gagnon’s Lake Monster Traditions. In many cases, those bestiaries are the sole reference for an entry, and these can in turn pass on errors. The “Celphie” as reported by Barber and Riches is one such example, as are the multiple misattributions and jokes concocted by Borges. The “zaratan” entry is a particularly bad offender, not only passing on Borges’ misspelling but also misrepresenting the chain of literary events, mistaking the modern translator Palacios for a medieval author (“… the Zaratan has entered Arab and Islamic legends through the work of the ninth-century zoologist Al-Jahiz, later refuted by the Spanish naturalist and author Miguel Palacios in his version of the Book of Animals, and thence copied into a ninth-century Anglo-Saxon bestiary…”).

Not as much of a problem on their own, these research and linguistic errors have since propagated and have become hard to eradicate. They are straightforward to correct with the right sources, but without them it is all too easy to take them at face value.

Summary

Giants, Monsters & Dragons has some concerning research issues, and lacks eye-candy artwork, but for a complete encyclopedia of a lot of mythical creatures you can do no better. While I would suggest not taking everything in it for granted, this remains an unavoidable milestone of the genre. Besides, I’ve read it a lot so I’ve got a soft spot for it. 4 out of 5 gigelorums, down to 3 if you’re a strict rater, research errors bother you, and you have no access to primary sources.