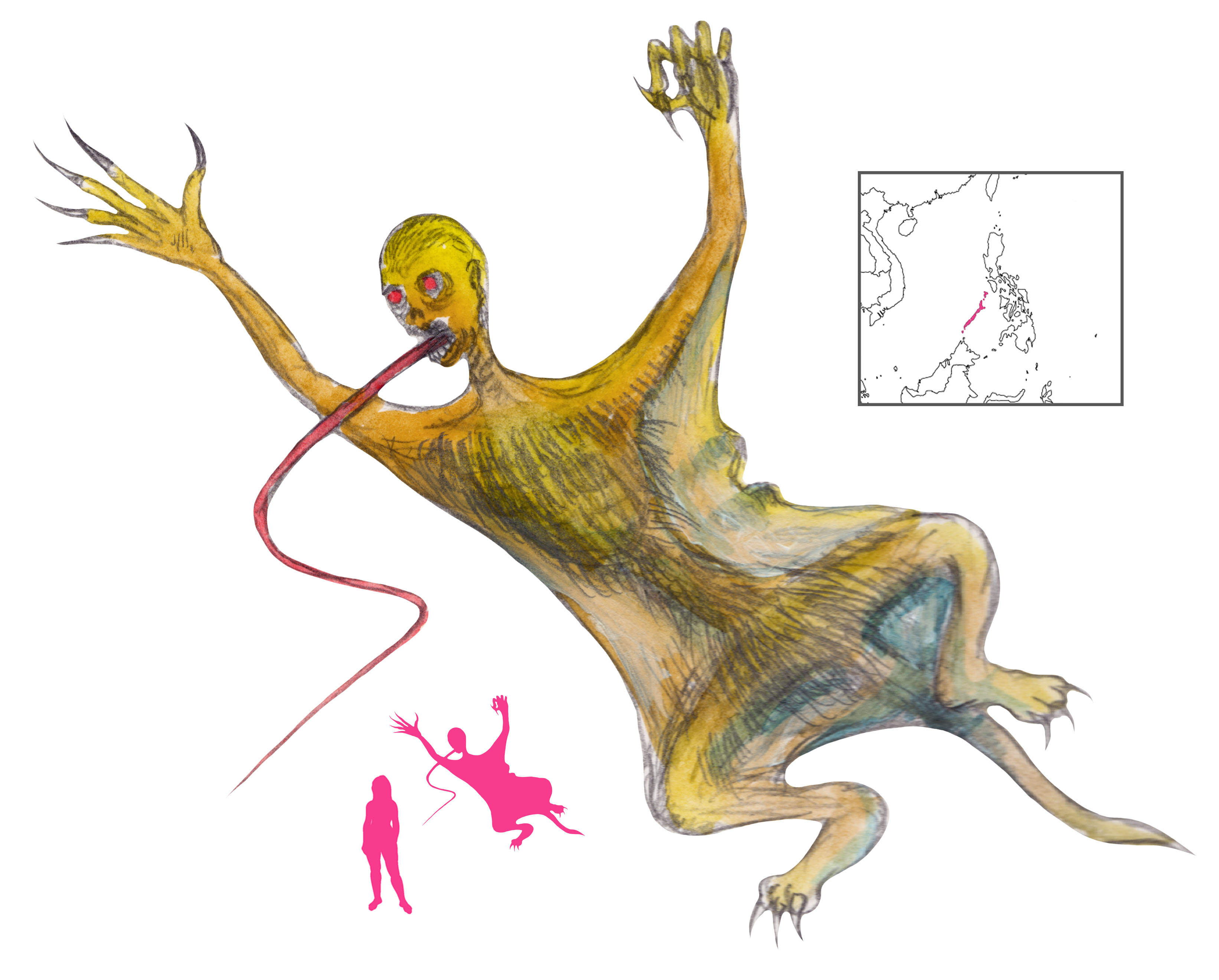

Variations: Malomba (pl.); Mulombe, Mulolo, Sung’unyi (Kaonde); Ndumba (Alunda); Man-Snake

The Ilomba is one of several familiar spirits associated with sorcerers and witchcraft in Zambia. Malomba appear as snakes with human heads and share the features and emotions of their owners. As malomba are obtained through deliberate sorcery in order to kill enemies or steal food, anyone suspected of having an ilomba is up to no good. That said, powerful chiefs and hunters are said to have their own malomba to protect them from witchcraft. Owners of malomba are usually male.

Evil sorcerers can make malomba in a number of ways. Most commonly, a mixture of certain medicines and water is made and placed on a piece of bark. Five duiker horns are placed next to this. A plait of luwamba or mbamba (spiky grass) is made to about 15-18 inches long and 0.5-1 inch wide; the duiker horns are placed at one end of this plait. Fingernail parings from the client are put in the horns, and blood taken from the client’s forehead and chest are mixed with the medicine. Some of the concoction is drunk by the client, while the rest is sprinkled onto the plait with a second luwamba plait. After the first sprinkling, the plait turns ash-white. The second sprinkling turns it into a snake. The third gives it a head and shoulders that resemble the client in miniature, including any jewelry present. The shoulders soon fade away to leave only the head.

The ilomba then addresses its master. “You know and recognize me, you see that our faces are similar?” When the client answers both questions in the affirmative, then they are given their ilomba.

Once obtained, an ilomba will live wherever the owner desires it to, but usually this is in riverside reeds. Soon it makes its first demand for the life of a person. The owner can then designate the chosen target, and the ilomba kills the victim. It kills by eating its victim’s life, by consuming their shadow, or by simply feasting on their flesh or swallowing them whole. Then it returns and crawls over its owner, licking them. People who keep mulomba become sleek and fat and clean, are possessed of long life, and will not die until all their relatives are dead. This comes at a steep price, however, as the ilomba will hunger again, and continue eating lives. If it is not allowed to feed itself, its owner will grow weak and ill until the ilomba feeds again.

Soon the unnatural death toll will be noticed, and a sorcerer is called in to divine the hiding place of the ilomba. To kill an ilomba, a sorcerer will sprinkle nsompu medicine around its suspected lair. This causes the water level to rise and the ground to rumble. First fish, then crabs, and finally the ilomba itself appear. The snake is promptly shot with a poisoned arrow – and its owner feels its pain. They die at the same time.

References

Melland, F. H. (1923) In Witch-bound Africa. J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

Turner, V. (1975) Revelation and Divination in Ndembu Ritual. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

White, C. M. N. (1948) Witchcraft, Divination and Magic among the Balovale Tribes. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 18(2), pp. 81-104.

The traumatized girl ran home in tears. When questioned by her father about her missing brother, she remembered the bulgu’s words and said “He got lost in the brush, he wandered off alone”. But all she could think of was her brother’s death and the ogre’s threat, and she refused to eat for days, wasting away. Eventually she became too weak to move, and called her father to her bedside. “Father, build me nine high, thick fences around the house, and I will tell you why my brother disappeared”. Nine palisades were constructed of juniper, and the daughter finally told all. The father was incensed. He built a platform of branches above the hut to hide his daughter, then seized his lance and went off to slay the bulgu.

The traumatized girl ran home in tears. When questioned by her father about her missing brother, she remembered the bulgu’s words and said “He got lost in the brush, he wandered off alone”. But all she could think of was her brother’s death and the ogre’s threat, and she refused to eat for days, wasting away. Eventually she became too weak to move, and called her father to her bedside. “Father, build me nine high, thick fences around the house, and I will tell you why my brother disappeared”. Nine palisades were constructed of juniper, and the daughter finally told all. The father was incensed. He built a platform of branches above the hut to hide his daughter, then seized his lance and went off to slay the bulgu.