Variations: Zabrak; Rukh (al-Marwazi); Phalmant (Bochart)

The Zabraq is one of the many exotic animals found in India. Bochart gave its location as the region of Dasht or Dist, the “gateway to Tartary”, and so presumably in the vicinity of Iran. It is also variously known as the Rukh and the Phalmant, although only the last term has seen use.

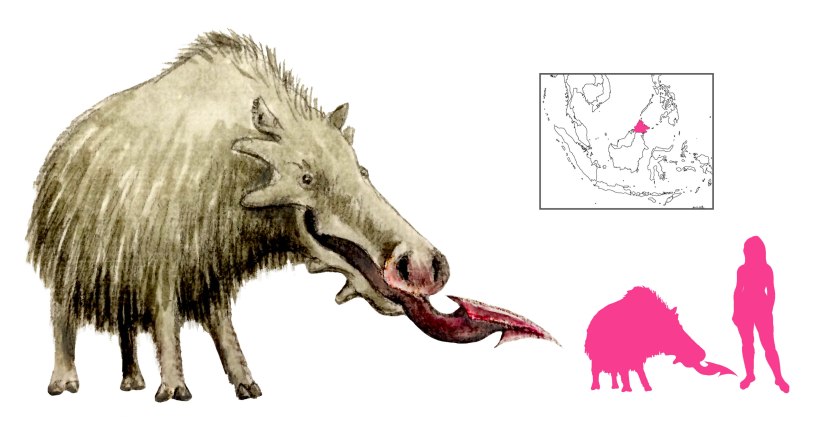

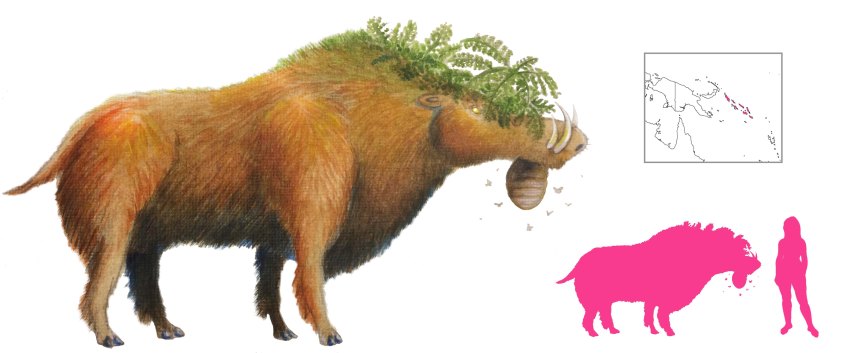

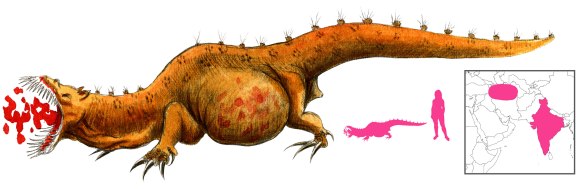

It is relatively modest in size, smaller than a cheetah, yellowish-red in color with flashing eyes and capable of leaping thirty to fifty cubits or more in one jump. Al-Marwazi makes it look like a camel, with two humps, tusks, and a large, membraneous tail, and adds that it is incredibly fast. Bochart, perhaps confusing its leaping distance with its size, makes it vast, prodigious, hideous, and forty cubits long, with bristling claws and teeth. Most importantly, it has highly acidic, weaponized urine and feces.

Zabraqs prey on animals up to the size of elephants, and kill them by flinging their caustic urine onto them with their tail. The tail of a zabraq can flatten and deform into a shovel shape to hold urine and dung before throwing it. The only animal zabraqs will avoid is the rhinoceros.

They are also fond of eating humans, and the only way to escape one is to climb a teak tree, which the zabraq cannot scale. Even that isn’t necessarily a safe place. When faced with treed prey, a zabraq will try to leap upwards and seize it before spouting its urine skyward, burning anything it touches like fire. However, if it cannot reach its prey through this stratagem, it turns towards the roots of the tree, roars in frustration until clots of blood erupt from its mouth, and expires.

Zabraq bile and testicles make potent poison; coated on weapons, it causes immediate death. Al-Marwazi goes further and specifies that the flesh, blood, saliva, and dung of the zabraq are all deadly.

Bochart reported this creature under the name of Phalmant and attributed it to Al-Damiri, although his account is entirely al-Mas’udi’s. Flaubert mentioned the phalmant it in his Temptation as a leopard howling so hard its belly bursts. The Dictionnaire Universel inexplicably turns it into a sea monster found on the coast of Tartary.

References

Berthelin, M. (1762) Abrégé du Dictionnaire Universel Francais et Latin, Tome III. Libraires Associés, Paris.

Bochart, S. (1675) Hierozoicon. Johannis Davidis Zunneri, Frankfurt.

Flaubert, G. (1885) La Tentation de Saint Antoine. Quantin, Paris.

Kruk, R. (2001) Of Rukhs and Rooks, Camels and Castles. Oriens, vol. 36, pp. 288-298.

al-Mas’udi, A. (1864) Les Prairies d’Or, t. III. Imprimerie Impériale, Paris.

Seznec, J. (1943) Saint Antoine et les Monstres: Essai sur les Sources et la Signification du Fantastique de Flaubert. PMLA, Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 195-222.