Variations: Shilalyi, Shulalyi, Šilali

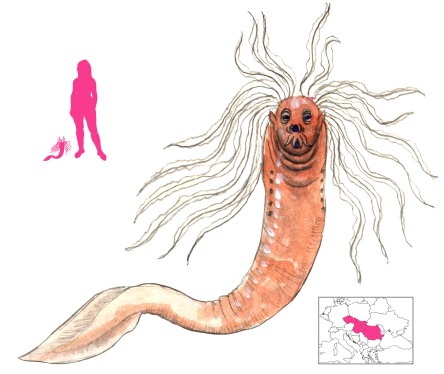

Schilalyi, “Cold” or “Cold One”, is the fifth of the children of Ana, and her third daughter. She and her siblings are the Roma demons of disease, and are the result of unnatural and undesired liaisons between the Keshali queen Ana and the King of the Loçolico.

After Ana’s fourth child, Melalo advised his father to serve her a cooked mouse which the King had spat on, along with soup. Ana fell ill, and as she drank water, Schilalyi crawled out of her mouth. This unnatural birth earned Schilalyi particular loathing from her mother. Schilalyi in turn tormented her brothers and sisters until her husband Bitoso was born.

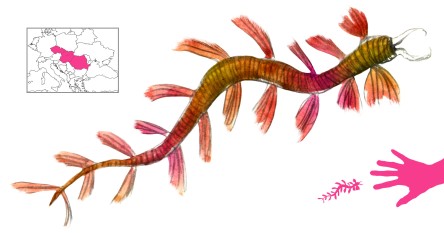

Schilalyi’s form is that of a white mouse with many little legs and possibly multiple tails, and she is the cause of chills and cold fevers. To counter her symptoms, patients are treated with dried mouse lungs and stomachs, steeped in alcohol.

White mice are regarded as agents and offspring of Schilalyi, leading to one alleged incident where a pharmacist’s lab mice were drowned in a well to ward off certain disaster.

References

Clébert, J. P. (1976) Les Tziganes. Tchou, Paris.

Clébert, J. P.; Duff, C. trans. (1963) The Gypsies. Vista Books, London.

Meyers Brothers Druggist (1910) Demons of Disease. Meyers Brothers Druggist, v. 31, p. 141.

Pavelčík, N. and Pavelčík, J. (2001) Myths of the Czech Gypsies. Asian Folklore Studies, v. 60, pp. 21-30.