Variations: Leucocrota, Leucocrote, Leucrocota, Leucrocuta, Leucrota, Leocrocota, Leoncerote; Corocotta, Korokottas, Krokottas, Krokottos, Krokouttas (Greek); Corocottas, Crocotta, Crocuta (Latin); Leoncerote

The Leucrocotta, unlike its close relative the corocotta, was not treated with any degree of seriousness by the ancients. There is only one primary textually corrupt record of it in Classical writing, it was never brought to Rome to the wonderment of all, and there are no contemporary depictions of it in art. And yet, the unique description it was given ensured not only that it would thrive in medieval writing, but also that it and the corocotta would eventually be hopelessly confused.

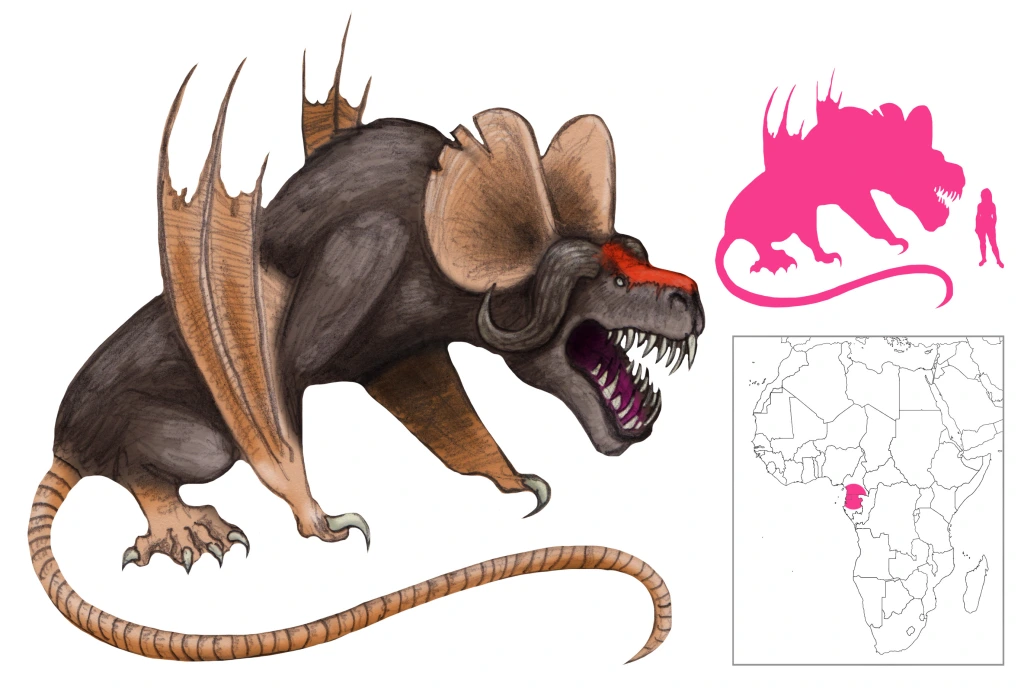

The only source for the leucrocotta is Pliny, who locates it in Ethiopia. It is as big as a wild donkey and has the cloven-hooved legs of stag, which enable it to run swiftly. It has the neck, tail, and breast of a lion, the head of a badger with a mouth slit all the way to the ears, and a single block of bone for teeth. Like the corocotta, it imitates the human voice.

Elsewhere Pliny says that the leucrocotta is the offspring of a lioness and a hyena (or corocotta). It has very sharp eyesight, a single continuous tooth in each jaw, and no gums. The single teeth are kept sharp by constantly rubbing against each other, and are enclosed in a sort of sheath.

The name of the leucrocotta itself is probably an error. Holland indicates that the best manuscripts of Pliny use the term leucocrota, which was then corrupted to leucrocota and its variants. The original may have been some kind of antelope, but the modified name gave it its origin from a lion and a corocotta (leo and crocotta).

Pliny’s copyist Solinus places the leucrocotta in India. It is as big as a donkey, haunched like a stag, with the breast and legs of a lion, the head of a camel, cloven hooves, a mouth that extends all the way back to the ears, and a single round bone instead of teeth. Its voice is like that of a man. It is the swiftest of all beasts.

Perhaps due to its clearly defined and unusual iconography, the leucrocotta found new popularity in medieval bestiaries, to the extent that it eclipsed the corocotta. The MS Bodley 764 bestiary says the leucrota is Indian, and is donkey-sized with the head of a horse, a lion’s chest and legs, a stag’s hindquarters, and cloven hooves. Its mouth is from ear to ear, it has a single bone in each jaw instead of teeth, and it imitates human speech.

Albertus Magnus makes reference to both the “cyrocrothes” and the “leucrocotham”. The Ortus Sanitatis brings further single-toothed creatures in the form of the “cirotrochea” and the “leucrocuta”.

Topsell’s crocuta is the same as the leucrocotta; it is an Ethiopian cross between a lioness and a hyena, with its teeth replaced by a single bone in each jaw. It imitates men’s voices and can break and digest anything.

Assuming the leucrocotta is a real animal, and stripping it of its confusion with the corocotta, its description evokes a large maned antelope. Ball suggests the nilgai as the origin of this chimera.

References

Ball, V. (1885) On the Identification of the Animals and Plants of India. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, II(6), pp 302-346

Barber, R. (1993) Bestiary. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge.

Borges, J. L.; trans. di Giovanni, N. T. (2002) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Vintage Classics, Random House, London.

Borges, J. L.; trans. Hurley, A. (2005) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Viking.

Brottman, M. (2012) Hyena. Reaktion Books, London.

Cuba, J. (1539) Le iardin de santé. Philippe le Noir, Paris.

Kitchell, K. F. (2014) Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon.

Magnus, A. (1920) De Animalibus Libri XXVI. Aschendorffschen Verlagbuchhandlung, Münster.

Pliny; Holland, P. trans. (1847) Pliny’s Natural History. George Barclay, Castle Street, Leicester Square.

Solinus, G. J. (1473) De Mirabilibus Mundi. N. Jenson, Venice.

Solinus, G. J.; Golding, A. trans. (1587) The Excellent and Pleasant Worke of Caius Julius Solinus. Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, Gainesville, Florida.

Topsell, E. (1658) The History of Four-footed Beasts. E. Cotes, London.

Unknown. (1538) Ortus Sanitatis. Joannes de Cereto de Tridino.