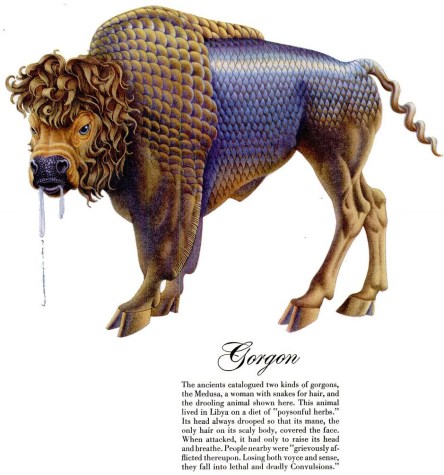

Okay, I’m cheating a little. Those aren’t exactly obscure or modern – in fact, they’re some of the best-known, oldest, and most enduring mythical creatures. But they are unique renditions of those creatures, and have influenced modern views of them in surprising ways, including providing the answer to a mystery that has plagued DnD scholars.

In its April 23, 1951 issue, LIFE Magazine ran a short (4 pages) article titled “Mythical Monsters”, subtitled “These Beasts Existed Only In Man’s Imagination”. It featured seven mythical creatures illustrated by another of my favorite illustrators, Rudolf Freund (I really need to do an effortpost on LIFE artists including Lewicki and Freund). They are beautiful, detailed, and feature some… unusual design choices.

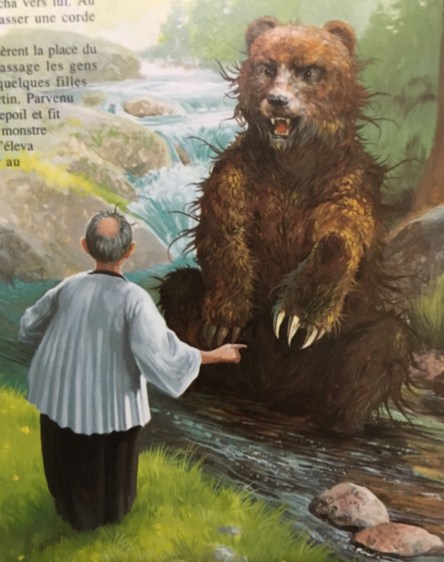

The depiction of the su is representative of Freund’s approach. Reading a mustached woman’s face, palm-frond tail, tiger stripes, frog babies, and ample udders into the description is definitely a first.

The griffin, on the other hand, is standard, although modern artists would give it eagle’s forelimbs. Pedants would argue that this isn’t a griffin but an opinicus. They’re wrong.

The yale in particular looks like it could actually exist, and I love the dynamic pose it’s in.

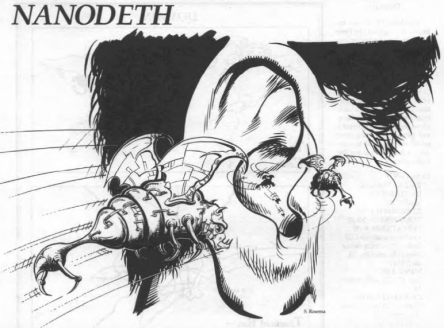

Going to go out on a limb here and claim that this here is the reason why so many basilisks today are drawn as lizards instead of little crowned snakes or freaky reptochickenmutants. Nothing in the text suggest anything lizardy either, so Freund may have been elaborating here.

Disclaimer: the break in its middle is because it’s spread across two pages.

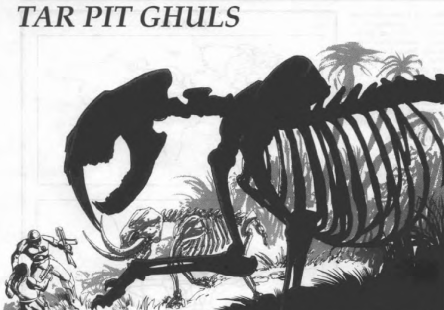

Looks familiar? That’s right, LIFE used Topsell’s gorgon (itself a renamed catoblepas). In turn, I humbly suggest that this was the inspiration for Dungeons and Dragons’ gorgon. You can stop worrying about where Gygax got his gorgon from and start sleeping easy.

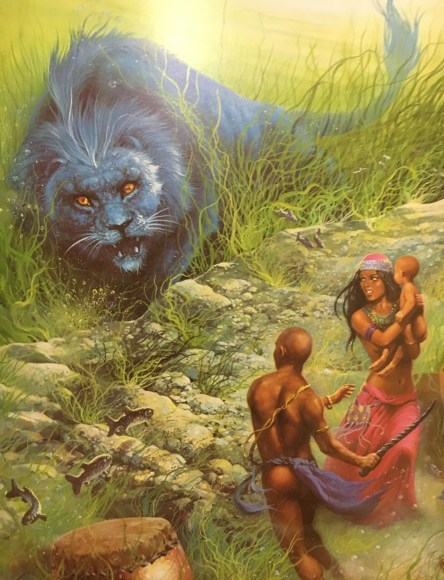

Freund’s manticore is scarier than anything else. It’s also the most dapper of manticores. Check out that handlebar mustache and the slicked hair! I suspect the manticore in Page and Ingpen’s encyclopedia of Things That Never Were was based in part on this. References to this manticore pop up in odd places, including…

… that one JLA comic where a manticore and a griffin double-team our heroes. The manticore is yellow, of course.

I always thought that was a cop-out weakness too.

The last and best is this spectacular unicorn. I love the different colors and the mismatched elephant feet. This is exactly what unicorns should look like – garbled third and fourth hand accounts of rhinos.