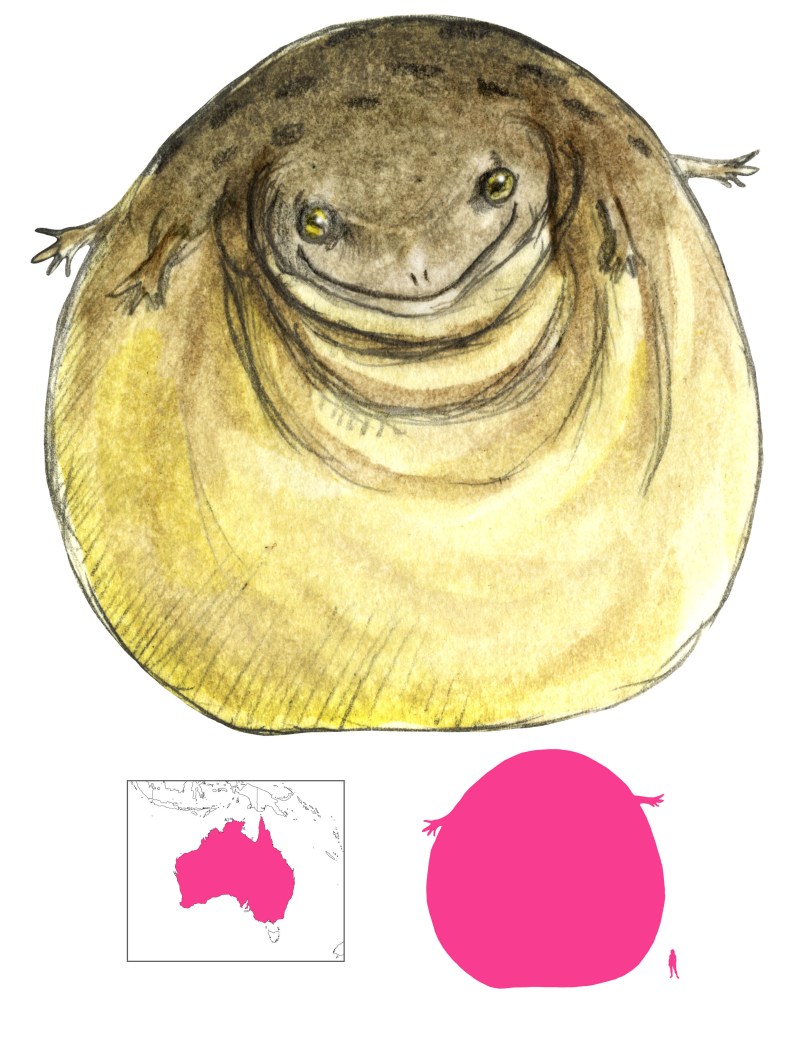

Variations: Tiddalick, Karaknitt

Tiddalik the frog was thirsty. He got up one day in the Australian bush and decided he needed more water. He began by drinking down all the water in his pond. After that, he crawled out of the hole left behind and drained the nearby waterholes. Then he swilled down the closest river, and followed its tributaries, drinking them down one by one. Billabongs and lakes were gobbled up, and Tiddalik grew bigger and bigger. Finally, once there was no water left in sight, Tiddalik stopped. He was now a bloated, mountainous creature filled with water and incapable of moving. He could only sit there and stare, content at last.

Soon, as the lack of water became painfully evident, the animals started to gather around Tiddalik. His size and thick skin made him impervious to anything they could do, and rain was nowhere in sight. It was Goorgourgahgah, the Kookaburra, who hit upon the solution. “We must make him laugh”, he said. “That way he’ll open his mouth and all the water will come out”.

As the champion laugher, Goorgourgahgah went first. He flew in front of Tiddalik’s face, laughing at the top of his lungs. He tumbled in the air, told jokes, and guffawed till he was hoarse. Tiddalik blinked impassively.

All the other animals tried their luck. Kangaroo turned somersaults. Koala made weird noises. Frilled Lizard ran around with his frill open. Wombat rolled around in the dirt. Brolga danced and squawked. But nothing they did seemed to get to Tiddalik, and the more they tried the thirstier they got. The monstrous frog merely continued to observe them with his globular eyes.

Then, as the other animals began to despair, Noyang the Eel stepped solemnly up. Everyone held their breath as Noyang straightened and balanced precariously on his tail. A ripple went through Tiddalik’s bloated body. Noyang began to twist and contort himself, forming hoops, spirals, springs, whirling around like a top… Tiddalik’s smile broadened, and he started to shake. Finally, Noyang tied himself in knots, and Tiddalik started to laugh hysterically – and all the water he held inside poured out, flooding the land before returning to its rightful place. Many died in the flood; Pelican took it upon himself to save as many as he could, but got aggressive when the human woman he wanted for a wife refused him. He painted his black feathers white to go to war, but was accidentally killed by another pelican who didn’t recognize him – pelicans today are both black and white in his honor.

When all had cleared, Tiddalik had shrunken back into a tiny frog once more. He had laughed so hard that he lost his voice, and could only croak hoarsely. Today, his descendants the water-holding frogs (Cyclorana platycephala) still practice every night in the hopes of regaining that voice, and still try to drink large quantities of water on a much smaller scale.

After losing all the water of the world, Tiddalik also came to resent anyone who tried to hoard water for themselves. When Echidna tried to keep a secret cache of water, it was Tiddalik who followed him and dove into the subterranean pond. “This water belongs to everyone!” he snapped. “You have no right to keep it to yourself!” The other animals punished Echidna by tossing him into a thornbush, and to this day he still has the thorns embedded in his back as a painful reminder of his greed.

References

Morton, J. (2006) Tiddalik’s Travels: The Making and Remaking of an Aboriginal Flood Myth. Advances in Ecological Research, vol. 39.

Ragache, C. C. and Laverdet, M. (1991) Les animaux fantastiques. Hachette.

Reed, A. W. (1965) Myths and Legends of Australia. A. H. and A. W. Reed, Sydney.

Reed, A. W. (1978) Aboriginal Legends: Animal Tales. A. H. and A. W. Reed, Sydney.