Variations: Alien Gods; Bil, Binaye Ahani, Ditsi’n, Hakaz Estsán, San, Sasnalkahi, Teelget, Tiein, Tse’nagahi, Tsenahale, Tsetahotsiltali, Ya’, Yeitso, and others

The Anaye or “Alien Gods” are a group of ancient monsters who plagued the Navajo. They were born as a result of a grand social experiment – the separation of the sexes. Early on in the history of humanity, men and women quarreled often. They tried living apart for a while, but boredom and starvation eventually reunited them.

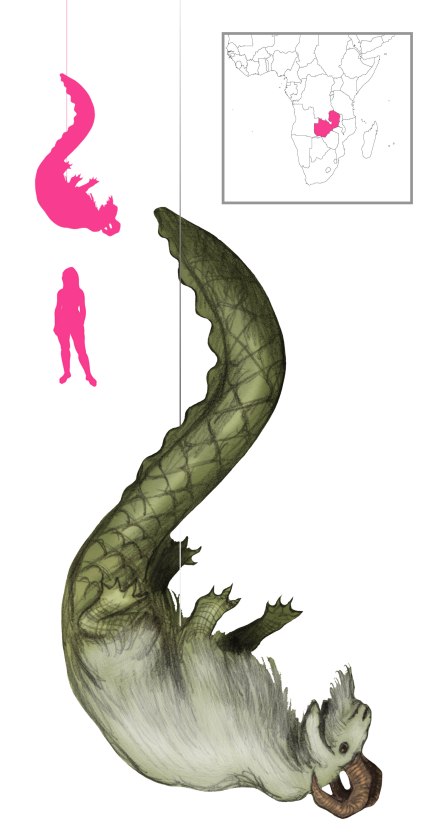

It was not without repercussions. The women who had been separated from the men resorted to various implements to relieve their sexual frustration. The Anaye were “fathered” by those unnatural acts, and their parentage was expressed in various ways. Yeitso, who was “fathered” by a stone, had flint armor; the horned Teelget’s “father” was an antler; the Tsenahale inherited their avian nature from a pile of feathers; and the limbless Binaye Ahani came from a sour cactus.

Each of the Anaye was born and abandoned by their horrified mothers, but survived long enough to become a threat. They ravaged the land, killing and eating as they pleased.

The Anaye reign of terror was brought to an end by the hero twins Nayenezgani, “Slayer of Alien Gods”, and To’badzistsini, “Child of Water”. They were the sons of Tsohanoai the Sun-carrier by Estsanatlehi, “Changing Woman”, and Yolkai’ Estsan, “White Shell Woman”, respectively.

The hero twins grew up rapidly and soon decided to find their father and their purpose. Along the way they met Spider Woman, who gifted them with a calming incantation and life-feathers that would protect them in the direst of circumstances. From Spider Woman’s house they passed through a series of environmental hazards. These included Tse’yeinti’li, the “Rocks that Crush”, a narrow chasm that would clap shut and kill travelers; Lokaadikisi, the “Cutting Reeds” with knifelike leaves; Xoc Detsahi the “Needle Cactus”, a field of animate cacti with vicious spines; Saitád the “Seething Sands”, mountainous dunes that engulfed climbers; and Totsozi the “Spreading Stream” that would widen itself to drown swimmers. Each of those malevolent terrain features were outwitted and subdued into turn.

When the twins reached Tsohanoai’s house they came face to face with two bear guardians, but Spider Woman’s sacred words calmed them. They did the same with two guardian snakes, two guardian winds, and two guardian lightnings, appeasing each in turn. Once inside the twins were hidden by Tsohanoai’s attendants in the four coverings of the sky to await their father.

Tsohanoai’s arrival was tempestuous. “Who are the two who entered today?” he bellowed. But the sun-carrier’s wife responded craftily. “Who are you to speak? Two youths came here looking for their father. If you see nobody but me, whose sons are these?” In a rage, Tsohanoai seized the bundle of robes and shook them out – the robe of the dawn, the robe of blue sky, the robe of yellow evening light, the robe of darkness – and the twins came tumbling out. He threw them against spikes of white shell in the East, spikes of turquoise in the South, spikes of haliotis in the West, and spikes of black rock in the North, and throughout it all they clung to Spider Woman’s feathers and were unharmed.

“I wish those were indeed my children”, sighed Tsohanoai. From then on he came to recognize his sons, and aided them in their quest to rid the world of the Anaye. After slaying their first Anaye, the titanic Yeitso, Tobadzistsini returned home to care for his and his brother’s mothers. But Nayenezgani earned his name that day, and went on to slay the remainder of the great Anaye. After Yeitso, Nayenezgani killed the carnivorous elk Teelget, the Tsenahale birds of prey, the kicking monster Tsetahotsiltali, the Binaye Ahani and their lethal gaze, Sasnalkahi the tracking bear, and many more besides.

But not all of the Anaye were killed. Tse’nagahi, the “Traveling Stone”, was spared after it swore to do no more evil. There was also a number of minor Anaye still in hiding – wretched, lonely, threadbare creatures that inspired pity rather than fear. Each of them managed to convince Nayenezgani of its importance in the scheme of things.

When Nayenezgani went to find San (Old Age), he found a wizened old woman, white-haired, bent and wrinkled. “I have come on a cruel errand, grandmother. I am here to kill you”, he said apologetically. “Why would you kill me?” she said weakly. “I have never harmed a single person. If you kill me then the human race will stand still. Boys will not become fathers. The old will not die and make room for the young. If you spare me I will help you increase the people”. So Nayenezgani spared San.

Then he set out to find Hakaz Estsán (Cold Woman). She lived on the highest peaks where snow lies on the ground all year. She was an old woman, lean, naked, shivering from head to toe, teeth chattering, eyes streaming constantly, with only snow-buntings for company. “Grandmother, I shall be a cruel man and kill you, that men may no longer die of cold”, he told her. “Kill me if you must”, chattered Hakaz Estsán. “But without me it will be permanently hot. The land will become dry. Water will disappear, and the people will perish in turn”. So Nayenezgani spared her as well.

Next was Tiein (Poverty). This was not one but two creatures, an old man and an old woman, both clad in filthy tattered rags and crouching in an empty house. “Grandmother, grandfather, I shall be a cruel man, for I am here to kill you” he stated. “Do not kill us”, said the old man. “Without us nothing would change, everything would be static. But we make clothing wear out and make people go out and fashion new and beautiful clothes. Let us live that people may continue making new things”. So Nayenezgani spared the couple.

Then there was Ditsi’n (Hunger). This was the chief of the Hunger People, and he was a massive, obese man with nothing to eat but the little brown cactus. “I shall be cruel”, announced Nayenezgani, “and kill you that people may no longer suffer of hunger”. But Ditsi’n said “Do not kill us, for without us, people would not care about food, they would not cook and prepare meals, they would lose the pleasures of hunting and cooking”. And they were spared as well.

Of the other minor Anaye less is told. We know that Ya’ (Louse) pleaded for its life, arguing that its presence taught compassion, that people would ask their friends to groom them, and so it was spared. As for Bil (Sleep), it made its case in a more direct (and humiliating) manner – by touching Nayenezgani with his finger and sending the hero into a blissful slumber.

Only then, when Nayenezgani had returned from sparing the last of the minor Anaye, did he and his brother rest. They went to the valley of the San Juan River, and they dwell there to this day.

References

Alexander, H. B. (1916) The Mythology of All Races v. X: North American. Marshall Jones Company, Boston.

Locke, R. F. (1990) Sweet Salt: Navajo folktales and mythology. Roundtable Publishing Company, Santa Monica.

Matthews, W. (1897) Navaho legends. Houghton Mifflin and Company, New York.

O’Bryan, A. (1956) The Diné: Origin Myths of the Navaho Indians. Bulletin 163 of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

Reichard, G. A. (1950) Navaho Religion: A Study of Symbolism. Bollingen Foundation Inc., New York.