Variations: Songomby, Songaomby, Tsiombiomby, Tsongomby, Bibiaombe; Brech, Brek (probably); Habeby, Fotsiandre (probably); Mangarsahoc (probably); Tòkantòngotra, Tòkandìa. Tokatomboka (probably)

The Songòmby is an unusual carnivorous animal from the folklore of Madagascar. The name may be derived from sònga, “having the upper lip turned upwards”, and òmby, “ox” according to Sibree. The word songòmby is taken to mean “lion-hearted” or “courageous”. Another name, bibiaombe , means “ox-animal”. Molet offers two derivations for songòmby: from the Swahili songo ngomby, “snake ox”, or a corruption of the alternative name tsiombiomby (“looks like an ox”). Domenichini-Ramiaramanana gives a popular etymology as derived from the question many ask when seeing it: Sangoa omby re izany? (“Isn’t that just an ox?”), and a more serious one from songo and omby where songo refers to virgin land allowed to go wild; in this case, the reference is to a feral ox.

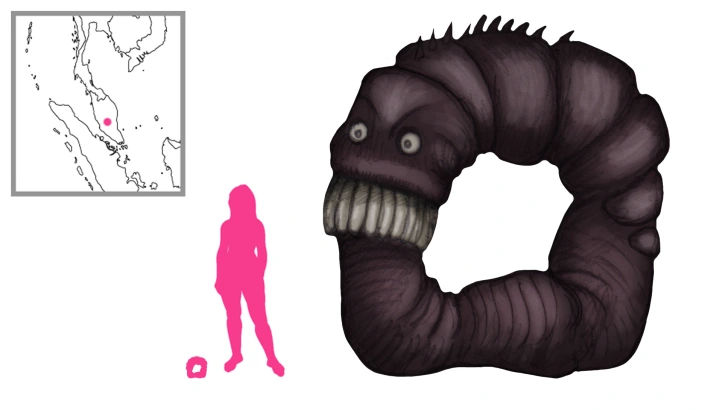

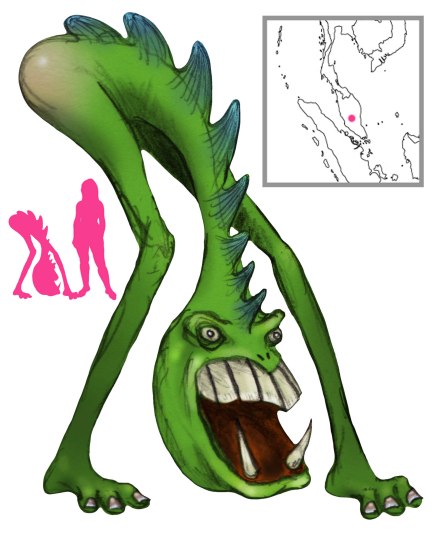

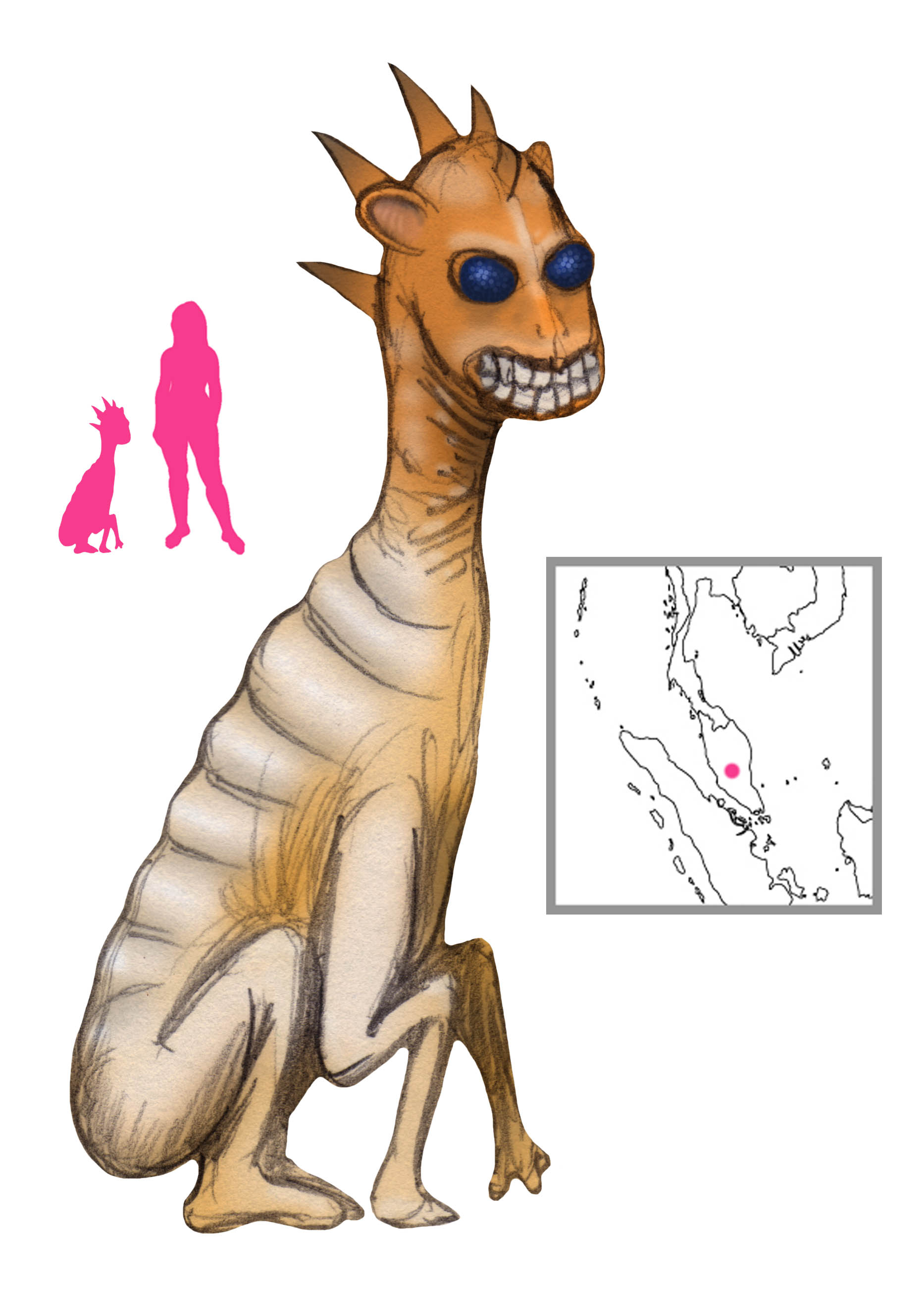

Consistent across the descriptions is that the songòmby is the size of an ox or a horse, exceedingly fast, burdened with floppy ears, and a man-eater. It looks something like a horse, a mule, or an ox. It has flaring nostrils and terrible incisors. Its prominent ears dangle over its eyes and can distract it at crucial moments.

Gabriel Ferrand says it has the body of an ox and a hornless horse’s head. It lives in forests and eats plants, insects, and humans. Its speed is beyond compare – a distant songòmby can reach its prey immediately. If its human prey tries to escape by climbing a tree, it will wait at the base of the tree and try to bring the human down by ruse. If that fails it directs a jet of urine at its prey. The victim loses their grip, falls, and is devoured by the songòmby.

R. P. Callet says the songòmby looks like a donkey with spots. It eats grass but if it sees people it chases them. It comes out at night to graze. When climbing mountains they are fast as horses, but when they go down they move slowly because their ears flop over their eyes.

Domenichini-Ramiaramanana describes the songòmby as white in color, very fast, like both a horse and an ox, and with a single horn. It sprinkles itchy hair (lay) from its nostrils. If its prey tries to escape by climbing a tree, the itchiness brought on by the lay will make the victim try to scratch itself, falling out of the tree. Thus, if climbing a tree to avoid a songomby, one must be sure to tie oneself to the branches with lianas. The creature is patient though and will wait till morning at the foot of the tree.

In northern Madagascar the songòmby is like the donkey or the mouflon. It has tufts of hair at its feet. It may have backswept horns or no horns at all. Its hooves are so hard they strike sparks from the ground. Most unusually of all, “it is only seen in profile and looking behind it”. This final clue suggests to Molet that the songòmby evolved from the decorative ch’i-lin on Chinese plates, which is often depicted in profile and looking backwards. The people of Madagascar would have seen those on Chinese plates brought by Arab traders – a trade which was stopped by the Portuguese, leaving the origin of the songòmby to distant history.

To catch a songòmby, a child is tied up in front of the songòmby’s den while a net is put over the entrance. The child’s crying attracts the songòmby, which is snared in the net. Worse than that, children were punished by putting them outside and telling them the songòmby would eat them. But this was not without its risks. A child was once put outside, and the parents called out “Here’s your share, Mr. Songòmby!” As luck would have it, a songòmby was passing by. “Oh, he really is here!” cried the child, but the parents ignored him, replying “Let him eat you!” thinking the child was mistaken. After a while they opened the door to find their child was gone. They followed the trail of blood all the way to the entrance of the songòmby’s cave.

Fortunately the songòmby is not invincible. A man going out by night once met a songòmby, but as he was strong and brave, fought it all night without being hurt. The hero Imbahitrila once defeated a songòmby by arming himself with two magical eggs from the angavola bird. They answered his wish to overcome the songòmby by causing it to trip and fall. Once on the ground the songòmby was easily slain by Imbatrihila’s spear.

The Tòkantòngotra or Tòkandìa (“single-hoof”) is very similar to the songòmby. It is white in color, large (but smaller than the songòmby). Its feet are single hooves, like those of a horse (but not one foot in front and one in the back, as some authors have interpreted). Like the songòmby, it is very fast, travels by night, and is a man-eater.

Flacourt describes an animal called the Mangarsahoc. It is a large beast with a horse’s round hooves and long dangling ears. When it comes down from the mountains, the ears cover its eyes and impair its vision. It brays like a donkey – and, indeed, Flacourt decides that it must be some kind of wild donkey. A mountain 20 leagues from Fort Dauphin is named Mangarsahoc after the animal. Flacourt also mentions an animal called the Brech or Brek, about the size of a goat kid and with a single horn on its forehead. It is very wild in nature. Flacourt determines that “it must be a unicorn”. Both of those seem close enough to the songòmby to be worth mentioning.

The Habeby or Fotsiandre (“white sheep”) looks like a white sheep with long, dangling ears, staring eyes, and short wool. Reclusive and shy, it is not carnivorous, but the description once again recalls the songòmby.

When the horse was first brought to Madagascar, it was believed to be a songòmby (it was eventually saddled with the name soavaly, derived from the French cheval).

References

Domenichini-Ramiaramanana, B. (1983) Du ohabolana au hainteny: langue, littérature et politique à Madagascar. Karthala, Paris.

de Flacourt, E. (1661) Histoire de la Grande Isle Madagascar. Francois Clouzier, Paris.

Molet, L. (1974) Origine Chinoise Possible de Quelques Animaux Fantastiques de Madagascar. Journal de la Soc. des Africanistes, XLIV(2), pp. 123-138.

Sibree, J. (1896) Madagascar Before the Conquest. Macmillan, New York.