Variations: Aspido-chelone, Aspidochelon, Aspidocalon, Aspidoceleon, Aspidodeleon, Aspidodelone, Aspischelone, Aspido-tortoise, Asp-tortoise, Asp-turtle, Fastitocalon, Shield-tortoise, Sea-monster, Sea-tortoise, Sea-turtle, Sulhafat, Turtle

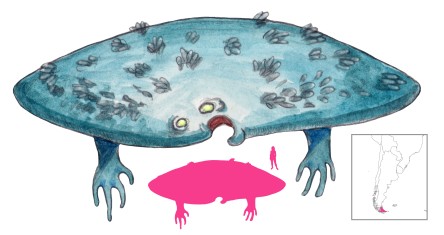

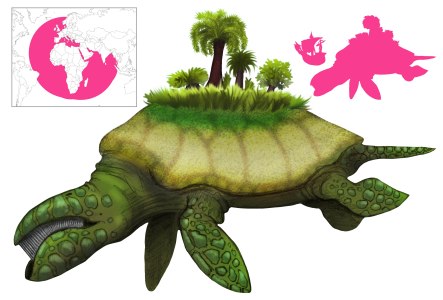

The motif of the island-turtle or island-whale is one of the most common and pervasive of maritime yarns. Whether it is a turtle, a whale, a fish, or a crab, the story is the same. A great sea creature raises its back out of the water. Sea-sand and vegetation gather in on its rough back, until it looks like a small island. Sailors anchor their ship to the deceptive “island”, disembark, and light a fire. The monster, feeling the fire on its back, immediately dives, taking the sailors and their ship down to a watery grave.

Prototypes of the gigantic fish are in the Indian Zend-Avesta, the supposed 3rd-Century letter of Aristotle to Alexander, and the Babylonian Talmud composed around CE 257-320.

The monster in al-Jahiz’s account is a crab (saratan) – surely confusion with the similarly shelled turtle? In al-Qazwini’s entry on the turtle (sulhafat), he distinguishes between the terrestrial tortoise and the sea turtle. The sea turtle is of great size, and sailors believe it to be an island in the middle of the sea, landing on it and lighting a fire until the turtle stirs, whereupon those aboard the ship call out “Come back, for it is a turtle that felt the heat of the fire, come back that you may not go down with it!” Sindbad the Sailor encountered this creature in his first Voyage, but managed to escape with his life.

The Account repeated in the Physiologus and bestiaries such as the Exeter Book, and the monster is identified with the whale that swallowed Jonah. The original Greek versions of the bestiary talk of the Aspidochelone – a name of uncertain etymology. Chelone refers to a turtle or tortoise, but aspido has been assumed to mean “shield” or “asp” (as in, the snake). The “shield” origin may stem from the turtle’s shell, but it seems like a redundant descriptor for a turtle. Another possibility is that the turtle was originally more of a serpent, or that this is a reference to the aspidochelone’s evil.

Whatever the meaning, the name aspidochelone became corrupted over time to become the “fastitocalon”, and the turtle supplanted with the more familiar whale (although the description of a rough back sounds more like a turtle’s shell).

The Physiologus or Bestiary adds further moralizing elements to the story. The aspidochelone will exhale a pleasant odor from its mouth, attracting fish that are then swallowed. Thus the aspidochelone is an allegory for Satan. Sinners who anchor themselves to the Devil are doomed to go to Hell, and sinful pleasures are enticing as perfume.

The aspidochelone entry is preceded by the panther entry. Both use fragrant breath to attract other animals, but the aspidochelone is evil while the panther is an allegory for Christ. The juxtaposition is probably intentional. The fragrant smell of the aspidochelone may also be derived from the odorous cetacean substance known as ambergris.

Aspidochelones are minor subjects in medieval woodcarvings, visible at Kidlington, Great Grandsden, Isleham, Swaffham Bulbeck, and Norwich Cathedral. They can be distinguished by the presence of ships and cooking-pots on their back, or with their mouths open to attract fish.

References

Barber, R. (1993) Bestiary. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge.

Borges, J. L.; trans. di Giovanni, N. T. (2002) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Vintage Classics, Random House, London.

Cook, A. S. (1821) The Old English Physiologus. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Cook, A. S. (1894) The Old English ‘Whale’. Modern Language Notes, 9(3), pp. 65-68.

Curley, M. J. (1979) Physiologus. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Druce, G. C. (1914) Animals in English Wood Carving. The Third Annual Volume of the Walpole Society, pp. 57-73.

Gordon, R. K. (1957) Anglo-Saxon Poetry. J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London.

Hippeau, C. (1852) Le Bestiaire Divin de Guillaume, Clerc de Normandie. A. Hardel, Caen.

Iannello, F. (2011) Il motive dell’aspidochelone nella tradizione letteraria del Physiologus. Considerazioni esegetiche e storico-religiose. Nova Tellus 29(2), pp. 151-200.

Al-Jahiz, A. (1966) Kitab al-Hayawan. Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi wa Awladihi, Egypt.

Al-Qazwini, Z. (1849) Zakariya ben Muhammed ben Mahmud el-Cazwini’s Kosmographie. Erster Theil: Die Wunder der Schöpfung. Ed. F. Wüstenfeld. Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, Göttingen.

White, T. H. (1984) The Book of Beasts. Dover Publications, New York.

Wiener, L. (1921) Contributions toward a history of Arabico-Gothic culture, volume IV: Physiologus studies. Innes and Sons, Philadelphia.