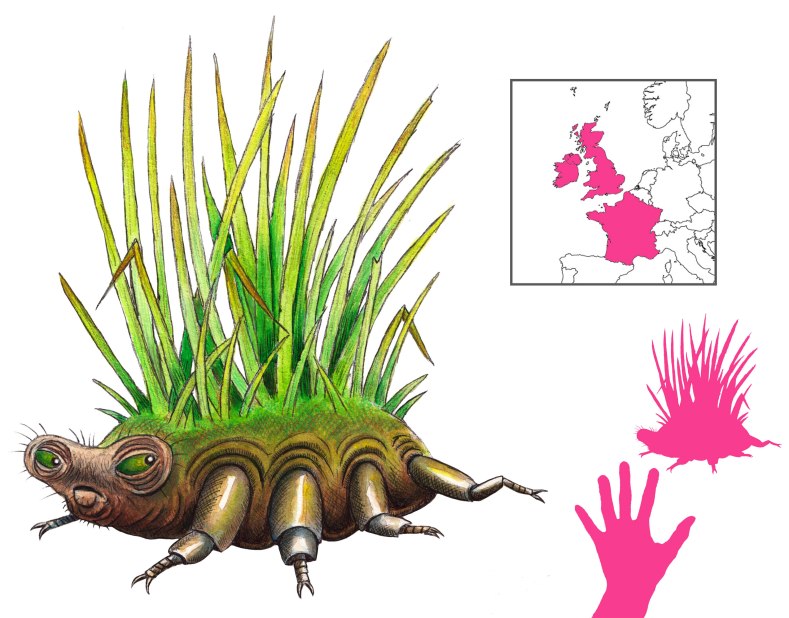

Variations: Muirgris (erroneously); Sínach, Sinech; Píast Uiscide (“Water Beast”); Úath (“Horror”)

Fergus mac Léti, the King of Ulster, was an inveterate swimmer. Captured while sleeping by water-spirits, the lúchorpáin or “small bodies” (actually the first appearance of leprechauns), he was awoken by the cold water they tried to carry him into. This allowed him to turn the tables on his would-be captors, and he seized three of the lúchorpáin. Fergus demanded that the sprites grant him three wishes: the ability to breathe underwater in seas, pools, and lakes.

The sprites granted him his wish, in the form of enchanted earplugs and a tunic to wear around his head. But like all wishes granted by the Fair Folk, it came with a caveat. Fergus was not to use his gifts at Loch Rudraige (Dundrum Bay) in his own land of Ulster.

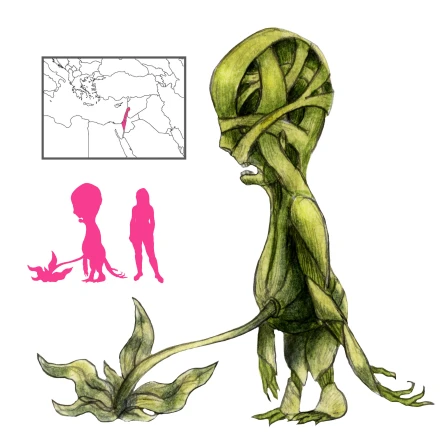

Of course, Fergus arrogantly disregards the rule and swims underwater at Loch Rudraige anyway. There he encounters the Muirdris, the “Sea Bramble” or “Sea Briar”, a huge, mysterious, undefined horror that inflates and deflates, expands and contracts like a bellows. It has features of a thorn-bush, with branches and stings, and its appearance alone is deadly.

Fergus does not take well to his encounter with the muirdris, and he is horribly disfigured after seeing it, with his mouth moving to the back of his head. His courtiers are dismayed, as a man with a blemish cannot be king, but they somehow keep this defacement a secret from Fergus for seven years. They prevent him from accessing mirrors, and surround him only with people who will protect the king’s deformity. He finds out only after Dorn, a highborn slave, taunts him about it after he strikes her with a whip. She is bisected for her troubles, and Fergus goes to face his nemesis alone.

The battle between Fergus and the muirdris lasts a day and a night, during which the water of the loch bubbles like a giant cauldron. Finally Fergus slays the monster with his bare hands, and emerges from the loch holding its head in triumph – only to collapse and die from the ordeal.

A thirteenth-century retelling of Fergus’ tribulations renames the monster sínach or sinech. In this version, it is the king’s wife who reveals his secret after an argument.

The muirdris is a monster, but is it rooted in fact? Surely the expansion and contraction, the comparison to a thornbush, and the disfiguring stings strongly suggest a large jellyfish, perhaps the lion’s mane jellyfish.

References

Borsje, J. (1996) From Chaos to Enemy: Encounters with Monsters in Early Irish Texts. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout.

MacKillop, J. (2005) Myths and Legends of the Celts. Penguin Books, London.