The Swan Valley Monster made its appearance on August 22, 1868, in the otherwise tranquil locale of Swan Valley, Idaho. Its presence was witnessed and reacted to by an unnamed old-timer crossing the river at Olds Ferry.

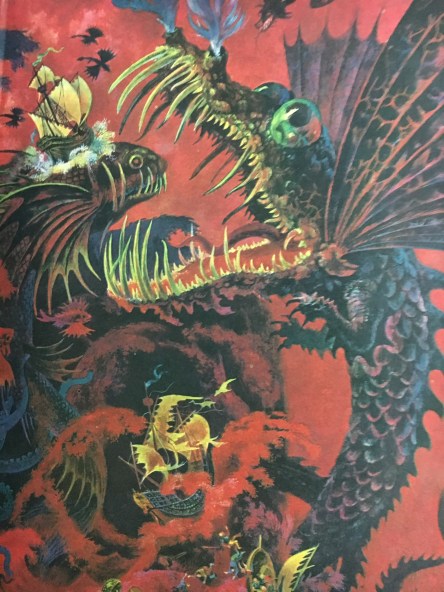

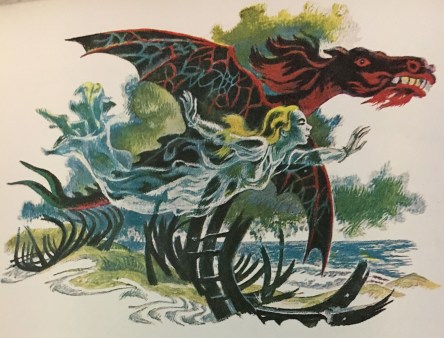

The first thing he saw of the monster was an elephant’s trunk rising from below the surface and spouting water. This was followed by a snake-like head the size of a washtub, with a single horn that kept moving up and down, and long black whiskers on both sides of the face. It had ten-inch-long fangs and a red forked tongue that spewed green poison. When it hauled its massive body onto the shore, the old-timer noted that it must have been twenty feet long, and it stank to high heaven. A pair of wing-like fins – or fin-like wings – came out of the sides of its neck. Its forward half was like a snake, the thickness of a calf, greenish-yellow with red and black spots; this in turn led into a fish-like section with hand-sized rainbow scales shining in the sun; finally, the tail was a drab, scaly gray like a crocodile or lizard tail. Shiny black barbed spines, like those of a porcupine, lined its back from head to tail. Finally, it had twelve stubby legs that were easily missed at first glance; the first pair under the fins had hoofs, followed by two pairs of legs with razor-sharp claws, then a pair of hoofed feet, a pair of clawed feet, and another pair of hoofed feet near the tail.

Of course, the old-timer’s first reaction to the abomination slithering up the bank was to fire a slug into its eye. The monster reared up, hissing, bellowing, and spurting poison over its surroundings, so it got shot a second time in its yellow belly, convulsed, and stopped moving. Everything its poison had touched, whether trees or grass or other living beings, withered and died.

As the monster was too large to be carried off by one man, the old-timer returned to town to fetch a wagon and six strapping lads to help him, as well as a tarp to protect them from the poison. They could smell the odoriferous creature a hundred yards away, and one of the men had to stay with the horses to keep them from bolting, while another got sick and refused to come any closer. But when they reached the bank where the monster had fallen, there was nothing but withered vegetation and a trail leading to the water.

Presumably the Swan Valley monster had crawled back into the river to die – or perhaps it didn’t die. Whatever its fate, the old-timer recommended keeping a close watch on the river, as “I’ve hunted an trapped an fished all over the state fer nigh ontuh seventy-five year… but I ain’t never seen nothin tuh compare with that speciment”.

References

Clough, B. C. (1947) The American Imagination at Work. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Fisher, V. ed. (1939) Idaho Lore. Federal Writers’ Project, The Caxton Printers, Caldwell.

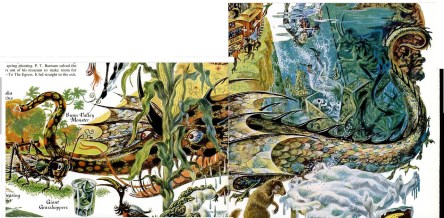

Lewicki, J. and the editors of LIFE (1960) Folklore of America, part V. LIFE Magazine, Aug. 22, 1960.