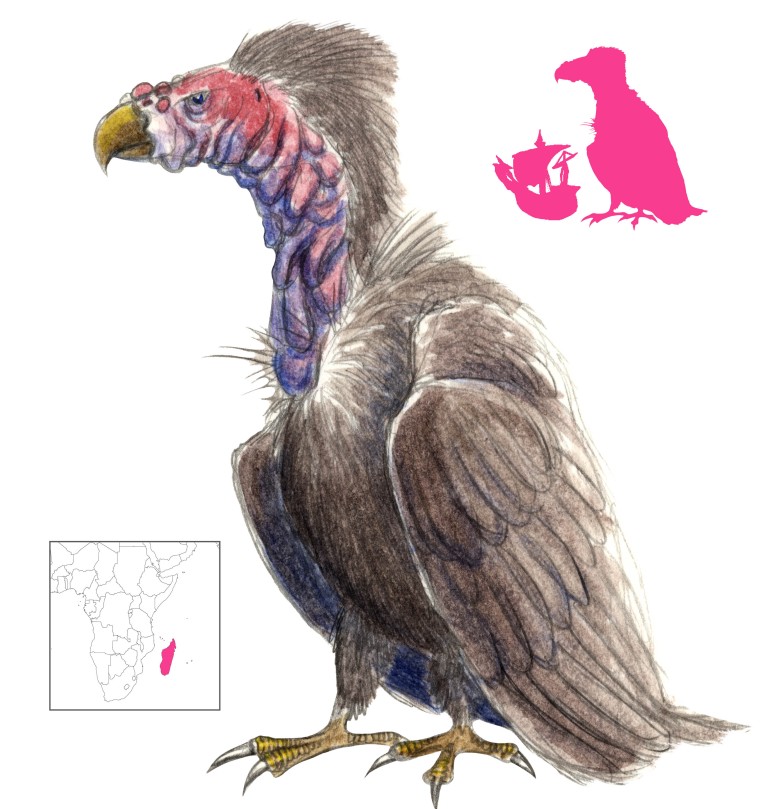

Variations: Rokh, Rukhkh, Roc, Ruc; Griffon, Griffin, Gryphon

The lineage of the Rukh (or, less correctly, Roc) is an ancient and venerable one, with tales of enormous birds stretching back into ancient Egypt. Generally believed to live in Madagascar (or possibly at the top of Mount Qaf), it is another iteration of the Arabian ‘Anqa, the Persian Simurgh, and the Indian Garuda and Cyena. The name rukh itself may have come about by a corruption of simurgh, which in turn came from cyena.

There is little defining the appearance of the rukh; it is a gigantic bird of prey, but what exactly that entails has varied from artist to artist. The only indisputable feature is that it is enormous. A rukh is as big as the storyteller needs it to be, leading to accounts of a hatchling rukh with wings a thousand fathoms (over 1800 meters) in length!

Rukhs are uncontested predators capable of feeding on the largest and most dangerous land animals. They have a particular fondness for giant serpents, elephants, and karkadanns or rhinoceroses. Sindbad observed that when a karkadann spears an elephant on its horn, the elephant’s fat runs into the rhino’s eyes and blinds it; a rukh will then swoop down and carry both combatants off to feed its chicks. Rukhs also appear to have some degree of intelligence, using boulders to smash prey.

The best-known interactions with rukhs were those of Sindbad the Sailor, who encountered them on his second and fifth voyages. The first time around, Sindbad found himself alone on a deserted island – not an uncommon occurrence in his life – and discovered a strange white dome, some fifty paces in circumference. As he pondered what the structure might be, the sky darkened as a huge rukh appeared. The dome was none other than its egg. Fortunately for Sindbad, it showed no interest in him as it sat on the egg and dozed off, and Sindbad tied himself to its leg with his turban, figuring that it might fly him to more civilized lands. In time the rukh awoke, screeched, and took off on the most terrifying ride of Sindbad’s life. When it finally landed he untied himself as fast as he could and ran for cover, while the rukh busied itself seizing a giant serpent in its talons and flying off with its prey.

Sindbad’s fifth voyage was even more catastrophic. This time, Sindbad’s crew went ashore without him and found the white dome of a rukh’s egg. Despite Sindbad’s warnings, they broke the egg and killed the chick inside. As they butchered the chick, the two parent rukhs appeared, their angry calls louder than thunder. When the sailors tried to flee in their ship, the birds returned with enormous boulders in their talons. The male’s rock narrowly missed the ship, but the female scored a direct hit, sinking the vessel. All sailors on board died with the exception of Sindbad, who drifted off towards further adventures.

In the tale of Aladdin, the evil necromancer attempts to convince Aladdin to demand a rukh egg to hang from the ceiling, a request which infuriates the genie. “You want me to hang our Liege Lady for your pleasure?” he roared, before informing them that such a wicked request could only have come from their enemy. In this case the author combined the rukh with the ineffably pure and holy simurgh.

Abd al-Rahman the Maghrebi, who had travelled far and wide across the world, obtained a rukh chick’s feather quill capable of holding a goatskin’s worth of water. He and his companions obtained it from a rukh chick that they cut out of an egg a hundred cubits long. The parent rukh flew after them and dropped a rock on their ship, but unlike Sindbad’s crew they successfully avoided it and went on their way. All those who had eaten the baby rukh’s flesh remained youthful and never grew old.

Ibn Battuta saw a rukh soaring over the China Seas. It was sufficiently far away to be mistaken for a flying mountain, and he and his companions were thankful that it did not notice them.

Marco Polo had the opportunity to observe rukhs on Madagascar; he believed them to be griffons, and specified that they were not half lion and half bird as he was led to believe, but simply enormous eagles. They had wings 30 paces long with feathers 12 paces long, and would pick up elephants and carry them into the air, dropping them onto the ground from great heights and feeding on the pulverized remains. A rukh feather was brought as a gift to the Great Khan, who was greatly pleased with it.

The rukh is not to be confused with al-Marwazi’s camel-like urine-spouting animal of the same name, described as zabraq by al-Mas’udi and as phalmant by Bochart. This grounded rukh may also be related to the rook chess piece, but both are far removed from the giant raptor.

The giant elephant bird Aepyornis of Madagascar, or its remains, was feasibly the origin of the rukh. It was, however, flightless, harmless, and non-elephantivorous. The rukh feathers that circulated as curiosities during the Middle Ages were fronds from the Madagascan Raphia vinifera palms.

References

Adler, M. N. (1907) The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. Oxford University Press, London.

Bianconi, G. G. (1862) Degli scritti di Marco Polo e dell’uccello ruc da lui menzionato. Tipi Gamberini e Parmeggiani, Bologna.

Burton, R. F. (1885) The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol. V. Burton Club, London.

Burton, R. F. (1887) Supplemental Nights to the Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol. III. Kamashastra Society, London.

Casartelli, L. C. (1891) Cyena-Simurgh-Roc: Un Chapitre d’Evolution Mythologique et Philologique. Compte Rendu du Congres Scientifique International des Catholiques, Alphonse Picard, Paris.

al-Damiri, K. (1891) Hayat al-hayawan al-kubra. Al-Matba’ah al-Khayriyah, Cairo.

Golénischeff, W. (1906) Le Papyrus No. 1115 de l’Ermitage Impérial. Recueil de Travaux Relatifs a la Philologie et a l’Archéologie Egyptiennes et Assyriennes, v. 12, pp. 73-112.

Kruk, R. (2001) Of Rukhs and Rooks, Camels and Castles. Oriens, vol. 36, pp. 288-298.

Payne, J. (1901) The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, vol. V. Herat, London.

Yule, C. B. (1875) The Book of Ser Marco Polo. John Murray, London.