Ah yes, the 90s, back when men were XTREME, women were XTREME, and toys were THE KOOLEST EVER. Toy manufacturers were constantly outdoing themselves in making XTREME action figures, and in a post-Transformers landscape, the importance of a storyline to enhance the play pattern was recognized.

Makers of toy cars in particular had to reinvent themselves. Making die-cast toys was becoming increasingly expensive, forcing them to cut corners (more on that in a later post); worse, they were losing in popularity to the XTREME newcomers. That’s when increasingly bizarre lines of “cars” were produced and died with a whimper. They were not huge sellers, but they were pretty cool- sorry, I mean XTREME. This post is dedicated to one such short-lived line.

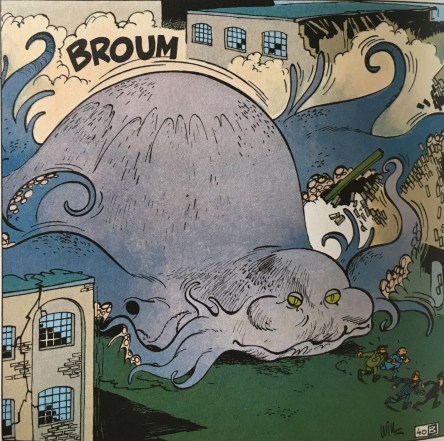

Matchbox’s Carnivores (Carnivores, get it?) were short-lived and obscure by any account. There was only one wave produced in 1995, and nothing else after that. The backstory was fairly flimsy – car-monsters battling each other in an XTREME post-apocalyptic landscape – and the marketing was half-hearted (Skull Shooter, for instance, didn’t even get advertised on the back of the packaging). They did make a catchy ad for them with a bit of claymation, though. Nowadays they lurk in the dark recesses of eBay.

What connection do I have with them? Back in 1995, I was presented with the opportunity of having either a Carnivore or The Illustrated Book of Myths. I chose the latter, obviously, but the toys and their box art remained etched in my young mind. It wasn’t until years later that I found out what those things were.

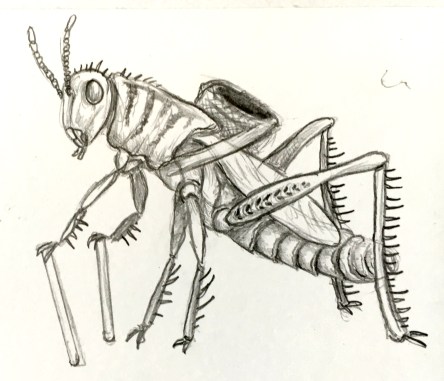

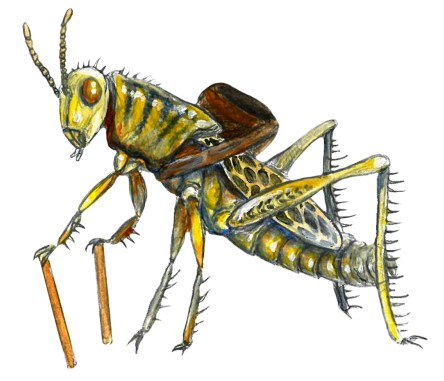

There were seven Carnivores in total. All of them had “Ax-L Action”, which is to say that the wheels made their legs move around like they were crawling forward. Two of those were “deluxes” slightly larger than the others and with more action features. As for the creatures themselves, well… let’s see what they have to offer. I will be using the box art because it’s even more gloriously monstery than the toys.

Iron Claw is fairly typical of the “basic” line, with crawling legs and a simple action feature – in this case, pressing the back claw causes the front claw to stab downwards. Iron Claw himself (only male pronouns are used, because girls aren’t allowed to play with XTREME car monsters) appears to be some kind of slug (or at least a mollusc), with a round sucker mouth, the eponymous iron claws, and an engine block in his back uncomfortably surrounded with tubercular tumorous tissue. He’s beautiful.

Buzz Off is much easier to narrow down: a giant car-wasp, with ragged membranous wings and three pairs of legs. And bull horns, apparently. But what’s with the chains? You will note that almost all the Carnivores have broken chains on their legs. Were they once tied up? Are they a top secret government experiment gone wrong? The world may never know.

Buzz Off’s gimmick is a “stinger missile”, a missile that can be spring-loaded and fired a short distance. It also appears to be sentient. Maybe they chat with each other in between dismembering prey.

A huge mouth, teeth, drool, wrinkly skin… Yup, this hits all the right buttons. Chomper’s gimmick is straightforward: he chomps stuff. This is the sort of thing that could keep you busy forever. Chomper seems rather toadlike, but I want to imagine that it’s a mutated horned lizard. And can also shoot blood from its eyeballs.

Spitfire is apparently some kind of squid? But it also has a ring of teeth and tentacles with claws attached to them? Yeah, I don’t know either. This one’s gimmick is spewing “deadly venom” – OK, water – that you load up and fire by pressing the soft plastic engine block on the back.

Skull Shooter, the zombie skeleton of the bunch, is the “secret” Carnivore, being largely unadvertised. He’s grabbing a pair of human skulls, so apparently the Carnivores share the Earth with us, and it gives us a sense of scale. He doesn’t seem to correspond with any known animal as far as I can tell.

Oh, and he shoots his own spring-loaded head off as a weapon. Metal.

Venom Spitter is one of the two “deluxe” Carnivores, and is a large creature that’s mostly mouth and which has stolen Spitfire’s venom-spewing powers. It’s not clear what it’s mean to be, but the first thing I think of when I see that huge mouth and those tusks is a hippopotamus.

Bite Wing, finally, is the other “deluxe” and is the most unconventional Carnivore, being not a car but a helicopter that evolved from some kind of mutated bat. It also has what seems to be an insect’s thorax and abdomen, so it’s another one of those darn GMOs.

It comes with not one, but two “parasite bombs” that look like secondarily flightless vampire bats. And they too seem to have a mind of their own. Do they make small talk while being carried by their “parent”? Do they monitor Carnivore activity from on high?Are they good cops or loose cannons? Do they like lattes? So many questions, but the closure of the line in 1995 means that there will never be answers.

Carnivores are © Matchbox.

Dear Alex S.,

Dear Alex S.,